Tests on Animals Demonstrate that New Eye Drops can Slow Vision Loss

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have developed eye drops that extend vision in animal models of a group of inherited diseases that lead to progressive vision loss in humans, known as retinitis pigmentosa. The eye drops contain a small fragment derived from a protein made by the body and found in the eye, known as pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF). PEDF helps preserve cells in the eye’s retina. A report on the study is published in Communications Medicine.

“While not a cure, this study shows that PEDF-based eye drops can slow progression of a variety of degenerative retinal diseases in animals, including various types of retinitis pigmentosa and dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD),” said Patricia Becerra, PhD, chief of NIH’s Section on Protein Structure and Function at the National Eye Institute and senior author of the study. “Given these results, we’re excited to begin trials of these eye drops in people.”

All degenerative retinal diseases have cellular stress in common. While the source of the stress may vary—dozens of mutations and gene variants have been linked to retinitis pigmentosa, AMD, and other disorders—high levels of cellular stress cause retinal cells to gradually lose function and die. Progressive loss of photoreceptor cells leads to vision loss and eventually blindness.

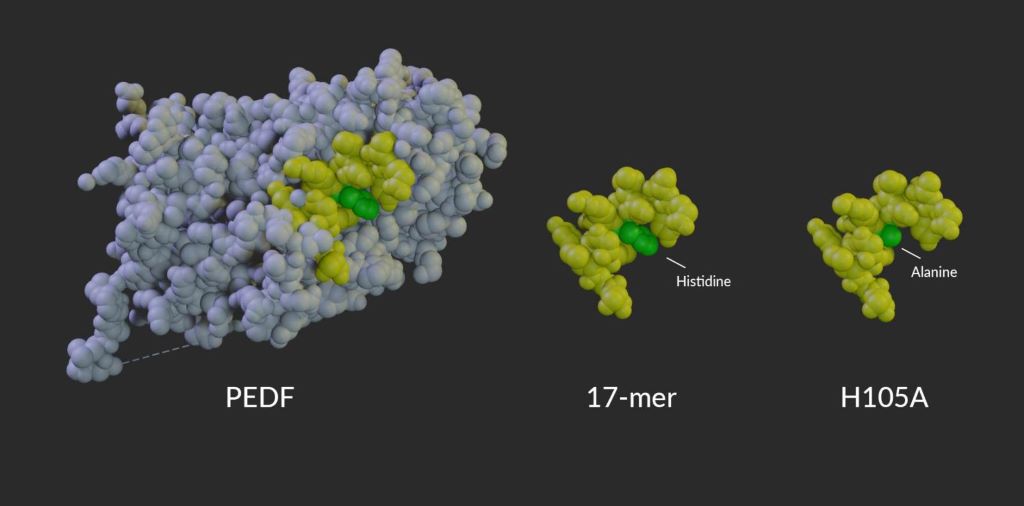

Previous research from Becerra’s lab revealed that, in a mouse model, the natural protein PEDF can help retinal cells stave off the effects of cellular stress. However, the full PEDF protein is too large to pass through the outer eye tissues to reach the retina, and the complete protein has multiple functions in retinal tissue, making it impractical as a treatment. To optimize the molecule’s ability to preserve retinal cells and to help the molecule reach the back of the eye, Becerra developed a series of short peptides derived from a region of PEDF that supports cell viability. These small peptides can move through eye tissues to bind with PEDF receptor proteins on the surface of the retina.

Model of PEDF protein alongside the 17-mer and H105A peptides. Amino acid 105, which is changed from histidine in PEDF and the 17-mer peptide to alanine in the H105A peptide, is shown in green.

In this new study, led by first author Alexandra Bernardo-Colón, Becerra’s team created two eye drop formulations, each containing a short peptide. The first peptide candidate, called “17-mer,” contains 17 amino acids found in the active region of PEDF. A second peptide, H105A, is similar but binds more strongly to the PEDF receptor. Peptides applied to mice as drops on the eye’s surface were found in high concentration in the retina within 60 minutes, slowly decreasing over the next 24 to 48 hours. Neither peptide caused toxicity or other side effects.

When administered once daily to young mice with retinitis pigmentosa-like disease, H105A slowed photoreceptor degeneration and vision loss. To test the drops, the investigators used specially bred mice that lose their photoreceptors shortly after birth. Once cell loss begins, the majority of photoreceptors die in a week. When given peptide eye drops through that one-week period, mice retained up to 75% of photoreceptors and continued to have strong retinal responses to light, while those given a placebo had few remaining photoreceptors and little functional vision at the end of the week.

“For the first time, we show that eye drops containing these short peptides can pass into the eye and have a therapeutic effect on the retina,” said Bernardo-Colón. “Animals given the H105A peptide have dramatically healthier-looking retinas, with no negative side effects.”

A variety of gene-specific therapies are under development for many types of retinitis pigmentosa, which generally start in childhood and progress over many years. These PEDF-derived peptide eye drops could play a crucial role in preserving cells while waiting for these gene therapies to become clinically available.

To test whether photoreceptors preserved through the eye drop treatment are healthy enough for gene therapy to work, collaborators Valeria Marigo, PhD and Andrea Bighinati, PhD, University of Modena, Italy, treated mice with gene therapy at the end of the week-long eye drop regimen. The gene therapy successfully preserved vision for at least an additional six months.

To see whether the eye drops could work in humans – without actually testing in humans directly – the researchers worked with Natalia Vergara, PhD, University of Colorado Anschutz, Aurora, to test the peptides in a human retinal tissue model of retinal degeneration. Grown in a dish from human cells, the retina-like tissues were exposed to chemicals that induced high levels of cellular stress. Without the peptides, the cells of the tissue model died quickly, but with the peptides, the retinal tissues remained viable. These human tissue data provide a key first step supporting human trials of the eye drops.

Source: NIH/National Eye Institute