How Much does Our HIV Response Depend on US Funding?

After the US slashed global aid, the South African government stated that only 17% of its HIV spending relied on US funding. But some experts argue that US health initiatives had more bang for buck than the government’s programmes. Jesse Copelyn looks past the 17% figure, and considers how the health system is being affected by the loss of US money.

In the wake of US funding cuts for global aid, numerous donor-funded health facilities in South Africa have shut down and government clinics have lost thousands of staff members paid for by US-funded organisations. This includes nurses, social workers, clinical associates and HIV counsellors.

Spotlight and GroundUp have obtained documents from a presentation by the National Health Department during a private meeting with PEPFAR in September. The documents show that in 2024, the US funded nearly half of all HIV counsellors working in South Africa’s public primary healthcare system. The data excludes the Northern Cape.

Counsellors test people for HIV and provide information and support to those who test positive. They also follow up with patients who have stopped taking their antiretrovirals (ARVs), so that they can get them back on treatment.

Overall, the US funded 1,931 counselors across the country, the documents show. Now that many of them have been laid off, researchers say the country will test fewer people, meaning that we’ll miss new HIV infections. It also means we’ll see more treatment interruptions, and thus more deaths.

PEPFAR also funded nearly half of all data capturers, according to the documents. This amounted to 2,669 people. Data capturers play an essential role managing and recording patient files. With many of these staff retrenched, researchers say our ability to monitor the national HIV response has been compromised.

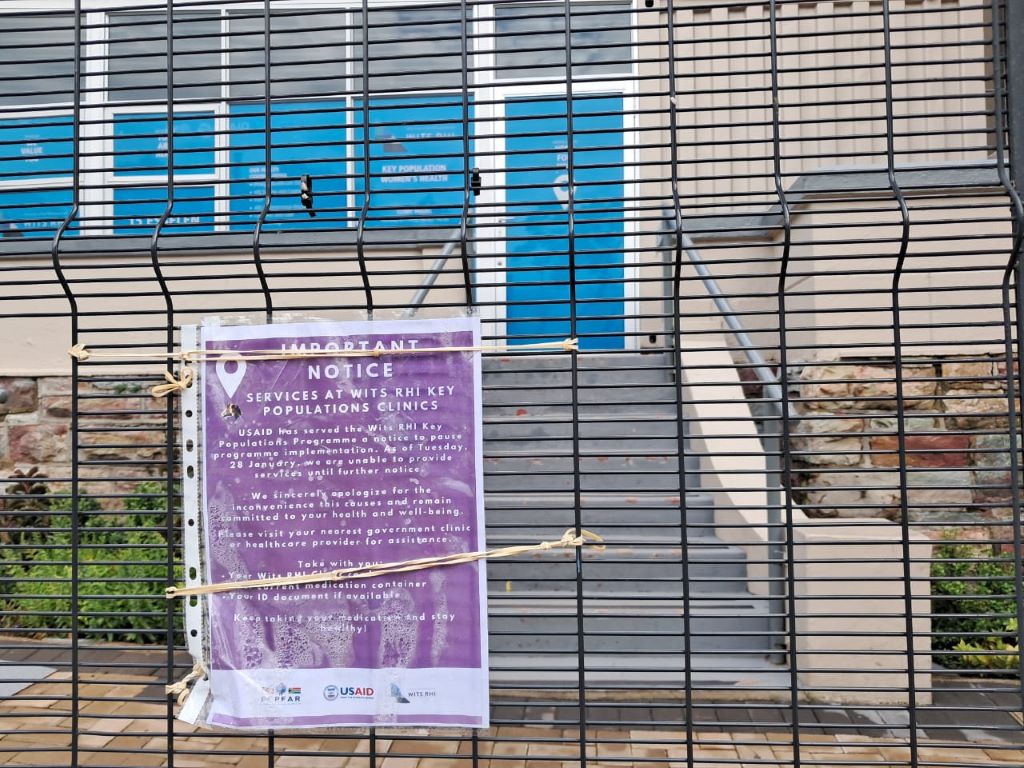

These staff members had all been funded by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The funds were distributed to large South African non-government organisations (NGOs), who then hired and deployed the staff in government clinics where there is a high HIV burden. Some NGOs received PEPFAR funds to operate independent health facilities that served high-risk populations, like sex workers and LGBTQ people.

But in late January, the US paused almost all international aid funding pending a review. PEPFAR funds administered by the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) have since resumed, but those managed by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) have largely been terminated. As a result, many of these staff have lost their jobs.

The national health department has tried to reassure the public that the country’s HIV response is mostly funded by the government, with 17% funded by PEPFAR – currently about R7.5 billion a year. But this statistic glosses over several details and obscures the full impact of the USAID cuts.

Issue 1: Some districts were heavily dependent on US funds

The first issue is that US support isn’t evenly distributed across the country. Instead, PEPFAR funding is targeted at 27 ‘high-burden districts’ – in these areas, the programme almost certainly accounted for much more than 17% of HIV spending. Some of these districts get their PEPFAR funds from the CDC, and have been less affected, but others got them exclusively from USAID. In these areas, the HIV response was heavily dependent on USAID-funded staff, all of whom disappeared overnight.

Johannesburg is one such district. A doctor at a large public hospital in this city told Spotlight and GroundUp that USAID covered a substantial proportion of the doctors, counsellors, clerks, and other administrative personnel in the hospital’s HIV clinic. “All have either had their contracts terminated or are in the process of doing so.”

The hospital’s HIV clinic lost eight counselors, eight data capturers, a clinical manager, and a medical officer (a non-specialised doctor). He said that this represented half of the clinic’s doctors and counselors, and about 80% of the data capturers.

This had been particularly devastating because it was so abrupt, he said. An instruction by the US government in late-January required all grantees to stop their work immediately.

“There was no warning about this, had we had time, we could have made contingency plans and things wouldn’t be so bad,” he explained. “But if it happens literally overnight, it’s extremely unfair on the patients and remaining staff. The loss of capacity is significant.”

He said that nurses have started to take on some of the tasks that were previously performed by counselors, such as HIV testing. But these services haven’t recovered fully and things were still “chaotic”.

He added, “It’s not as if the department has any excess capacity, so [when] nurses are diverted to do the testing and counselling, then other parts of care suffer.”

Issue 2: PEPFAR programmes got bang for buck

Secondly, while PEPFAR may only have contributed 17% of the country’s total HIV spend, some researchers believe that it achieved more per dollar than many of the health department’s programmes.

Professor Francois Venter, who runs the Ezintsha research centre at WITS university, argued that PEPFAR programmes were comparatively efficient because they were run by NGOs that needed to compete for US funding.

“PEPFAR is a monster to work for,” said Venter, who has previously worked for PEPFAR-funded groups. “They put targets in front of these organisations and say: ‘if you don’t meet them in the next month, we’ll just give the money to your competitors’ and you’ll be out on the streets … So there’s no messing around.”

US funding agencies, he said, would closely monitor progress to see if organisations were meeting these targets.

“You don’t see that with the rest of the health system, which just bumbles along with no real metrics,” said Venter.

“The health system in South Africa, like most health systems, is not terribly well monitored or well directed. When you look at what you get with every single health dollar spent on the PEPFAR program, it’s incredibly good value for money,” he said.

Not only were the programmes arguably well managed, but PEPFAR funds were also strategically targeted. Public health specialist Lynne Wilkinson provided the example of the differentiated service delivery programme. This is run by the health department, but supported by PEPFAR in one key way.

Wilkinson explained that once patients are clinically stable and virally suppressed they don’t need to pick up their ARVs from a health facility each month as it’s too time-consuming both for them and the facility. As a result, the health department created a system of “differentiated service delivery”, in which patients instead pick up their medication from external sites (like pharmacies) without going through a clinical evaluation each time. But Wilkinson noted that before someone can be enrolled in that service delivery model, clinicians need to check that patients are eligible.

“Because [the enrollment process] was going very slowly … this was supplemented by PEPFAR-funded clinicians who would go into a clinic and review a lot of clients, and get them into that system”. By doing this, PEPFAR-funded staff successfully resolved a major bottleneck in the system, she said, reducing the number of people in clinics, and thus cutting down on waiting times.

Not everyone is as confident about the overall PEPFAR model. The former deputy director of the national health department, Dr Yogan Pillay, told Spotlight and GroundUp that we don’t have data on how efficient PEPFAR programmes are at the national level. This needs to be investigated before the health department spends its limited resources on trying to revive or replicate the programmes, argued Pillay who is now the director for HIV and TB delivery at the Gates Foundation.

While he said that many PEPFAR-funded initiatives were providing crucial services, Pillay also argued that “the management structure of the [recipient] NGOs is too top-heavy and too expensive” for the government to fund. Ultimately, we need to consider and evaluate a variety of HIV delivery models instead of rushing to replicate the PEPFAR ones, he said.

Issue 3: PEPFAR supported groups that the government doesn’t reach

An additional issue obscured by the 17% figure is that PEPFAR specifically targeted groups of people that are most likely to contract and transmit HIV, like people who inject drugs, sex workers, and the LGBTQ community. These groups, called key populations, require specialised services that the government struggles to provide.

Historically, PEPFAR has given NGOs money so that they could help key populations from drop-in centres and mobile clinics, or via outreach services. All of this operated outside of government clinics, because key populations often face stigma in these settings and are thus unwilling to go there.

For instance, while about 90% of surveyed sex workers say that staff at key populations centres are always friendly and professional, only a quarter feel the same way about staff at government clinics. This is according to a 2024 report, which also found that many key populations are mistreated and discriminated against at public health facilities. (Ironically, health system monitoring organisation Ritshidze, which conducted the survey, has been gutted by US funding cuts.)

While the key populations centres funded by the CDC are still operational, those funded by USAID have closed. The health department has urged patients that were relying on these services to go to government health facilities, but researchers argue that many simply won’t do this.

Venter explained: “For years, I ran the sex worker program [at WITS RHI, which was funded by PEPFAR] … Because sex workers don’t come to [health facilities], you had to provide outreach services at the brothels. This meant … we had to deal with violence issues, we had to deal with the brothel owners, and work out which days of the week, and hours of the day we could provide the care. Logistically, it’s much more complex than sitting on your bum and waiting for them to come and visit you at the clinic.

“So you can put up your hand and say: ‘Oh they can just come to the clinics’ – like the minister said. Well, then you won’t be treating any sex workers.” Venter said this would result in a public health disaster.

He argued that one of the most crucial services that key populations may lose access to is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a daily pill that prevents HIV.

While the vast majority of government clinics have PrEP on hand, they often fail to inform people about it. For instance, a survey of people who are at high-risk of contracting HIV in KwaZulu-Natal found that only 15% were even aware that their clinic stocked PrEP.

Another large survey found that at government facilities, only 19% of sex workers had been offered PrEP. By contrast, at the drop-in centres for key populations, the figure was more than double this, at 40%. Without these centres, the health system may lose its ability to create demand for the drug among the most high-risk groups.

One health department official told Spotlight and GroundUp that the bulk of the PrEP rollout would continue despite the US funding cuts. “The majority of the PrEP is offered through the [government] clinics,” she said, 96% of which have the drug.

However, she conceded that specific high-risk groups like sex workers have primarily gotten PrEP from the key populations centres, rather than the clinics. “This is the biggest area where we are going to see a major decline in uptake for [PrEP] services,” she said.

600 000 dead without PEPFAR?

Overall, the USAID funding cuts have severely hindered the HIV testing programmes, data capturing services, PrEP roll-out, and follow-up services for people who interrupt ARV treatment. And the patients who are most affected by this are those that are most likely to further transmit the virus.

So what will the impacts be? According to one modelling study, recently published in the Annals of Medicine, the complete loss of all PEPFAR funds could lead to over 600 000 deaths in South Africa over the next decade.

While South Africa still retains some PEPFAR funding that comes from the CDC, beneficiaries are bracing for this to end. According to Wilkinson, the PEPFAR grants of most CDC-funded organisations end in September and future grants are uncertain. For some organisations, the money stops at the end of this month.

Meanwhile, if the government has any clear plan for how to manage the crisis, it’s certainly not making this public.

In response to our questions about whether the health department would be supporting key populations centres, the department’s spokesperson, Foster Mohale, said: “For now we urge all people living with HIV/AIDS and TB to continue with treatment at public health facilities.”

When pressed for details about the department’s plans for dealing with the US cuts, Mohale simply said that they could not reveal specifics at this stage and that “this is a work in progress”.

In his budget speech in Parliament on Wednesday, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana did not announce any funding to cover the gap left by the abrupt end of US support for the country’s HIV response. Prior to the speech, Godongwana told reporters in a briefing that the Department of Health would assist with some of the shortfall, but no further information could be provided.

Published by GroundUp and Spotlight.

Republished from GroundUp under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Read the original article.