Researchers Discover Stem Cells in the Thymus

Researchers have identified stem cells in the human thymus for the first time. These cells represent a potential new target to understand immune diseases and cancer and how to boost the immune system. Their reported their discovery in the journal Developmental Cell.

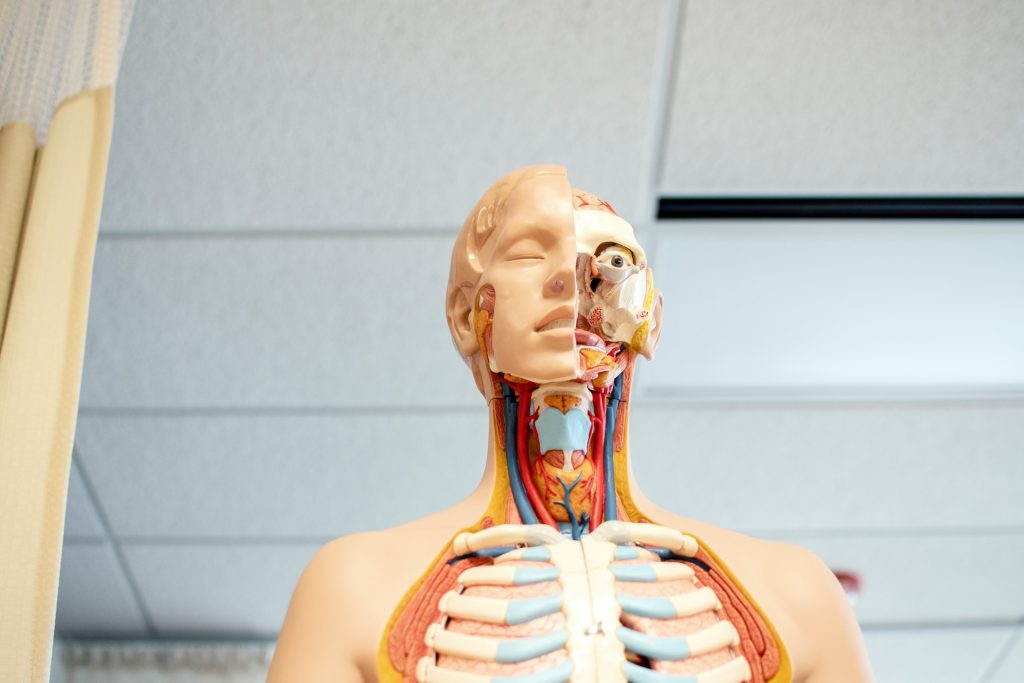

The thymus is a gland located in the front part of the chest, the place where thymocytes (the cells in the thymus) mature into T cells, specialised immune cells crucial to fighting disease. The thymus has a unique and complex 3D structure, including an epithelium (a lining of cells able to guide T cell maturation) that forms a mesh throughout the whole organ and around the thymocytes.

Owing to its relatively inaccessible location, comparatively recent discovery and the fact that it shrinks with age, the thymus has only been investigated for a short period of time compared to other organs. Until now, scientists believed it didn’t contain ‘true’ epithelial stem cells, but only progenitors arising in foetal development.

However, these findings from researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, show for the first time the presence of self-renewing stem cells, which give rise to the thymic epithelial cells instructing thymocytes to become T cells. This suggests the thymus plays an important, regenerative role beyond childhood, which could be exploited to boost the immune system.

In the course of their experiments, the researchers examined these stem cells based on the expression of specific proteins in the human thymus. They identified stem-cell niches (areas where stem cells are clustered) in two locations in the thymus: underneath the organ capsule, or outer layer, and around blood vessels in the medulla, the central part.

They demonstrated that thymic stem cells contribute to the environment by producing proteins of the extracellular matrix, which functions as their own support system.

By using state-of-the-art techniques to map gene expression in single cells and tissue sections, they found that these stem cells, named Polykeratin cells, express a variety of genes allowing them to give rise to many cell types not previously considered to have a common origin. They can develop into epithelial as well as muscle and neuroendocrine cells, highlighting the importance of the thymus in hormonal regulation.

The researchers isolated Polykeratin stem cells in a dish and were able to show that thymus stem cells can be extensively expanded. They demonstrated that all the complex cells in the thymus epithelium could be produced from a single stem cell, highlighting a remarkable and yet untapped regenerative potential.

Roberta Ragazzini, postdoctoral research associate at the Crick and UCL, and first author, said: “It’s paradoxical that stem cells in the thymus – an organ which reduces in size as we get older – regenerate just as much as those in the skin – an organ which replaces itself every three weeks. The fact that the stem cells give rise to so many different cell types hints at more fundamental functions of the thymus into adulthood.”

It’s understood that the thymus’ activity is tightly regulated in adults, providing enough immune support to fight infections but not overshooting to the degree of attacking the body’s own cells.

However, in certain people, the thymus isn’t working properly, or their immune system has reduced capacity. Today’s findings suggest it could be helpful in these cases to stimulate the stem cells to regrow the thymus and rejuvenate their immune system.

Paola Bonfanti, senior group leader of the Epithelial Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Laboratory at the Crick, said: “This research is a pivotal shift in our understanding of why we have a thymus capable of regeneration. There are so many important implications of stimulating the thymus to produce more T cells, like helping the immune system respond to vaccinations in the elderly or improving the immune response to cancer.”

The researchers will next study thymic stem cell properties throughout life and how to manipulate them for potential therapies.

Source: The Francis Crick Institute