T-helper Cells Near the Gut are Deliberately ‘Dysfunctional’

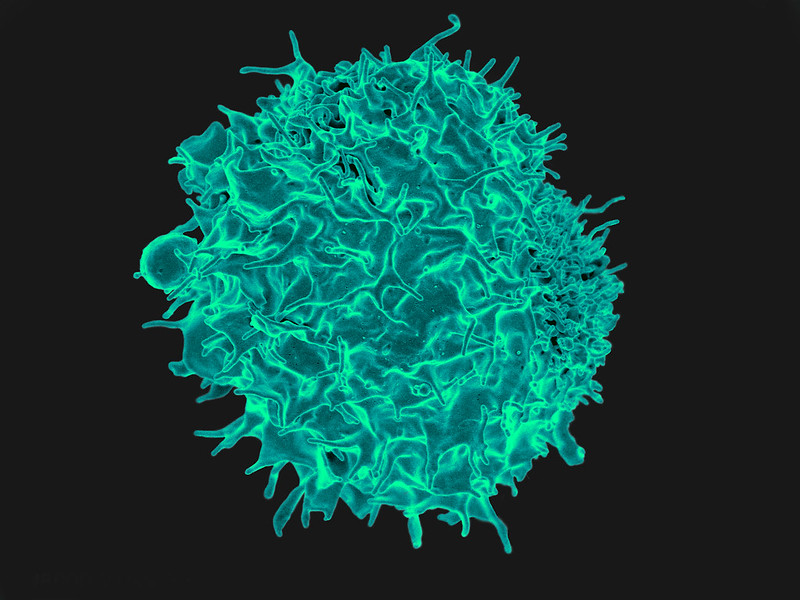

A new study published in Nature has found that certain food proteins can cause T-helper cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue to become dysfunctional in order for the immune system not to attack that particular food. Understanding how the process could be restarted could aid the development of food allergy treatments.

Led by Marc Jenkins, director of the University of Minnesota Medical School’s Center for Immunology, the research focused on why the immune system does not attack food in the way that it attacks other foreign entities like microbes.

“This study helps explain why our immune systems do not attack our food even though it is foreign to our bodies,” said Jenkins. “We found that ingested food proteins stimulate specific lymphocytes in a negative way. The cells become dysfunctional and eventually acquire the capacity to suppress other cells of the immune system.”

The gut associated-lymphoid tissue is a suppressive environment where lymphocytes that would normally generate inflammation undergo arrested development. This abortive response usually prevents dangerous immune reactions to food.

The research found that T-helper cells lack the inflammatory functions needed to cause gut pathology and yet the cells have the potential to produce regulatory T-cells that may suppress it. This means when people develop an intolerance or allergic reaction to certain foods, there may be a future capability to suppress that reaction by reintroducing dysfunctional lymphocytes.

Further research is needed to identify the mechanisms whereby food-specific lymphocytes become dysfunctional, knowledge which could be used to fight food allergies.