Controlling Allergic Asthma without Compromising Flu Resistance

Blocking calcium signalling in immune cells suppresses allergic asthma, but without compromising the immune defence against flu viruses, according to the findings of a new study published in Science Advances.

The researchers showed that, in a mouse model, removing the gene for a certain calcium channel reduced asthmatic lung inflammation caused by house dust mite faeces, a common cause of allergic asthma. Blocking signals sent through this channel, the calcium release-activated calcium (CRAC) channel, with an investigational inhibitor drug had a similar effect.

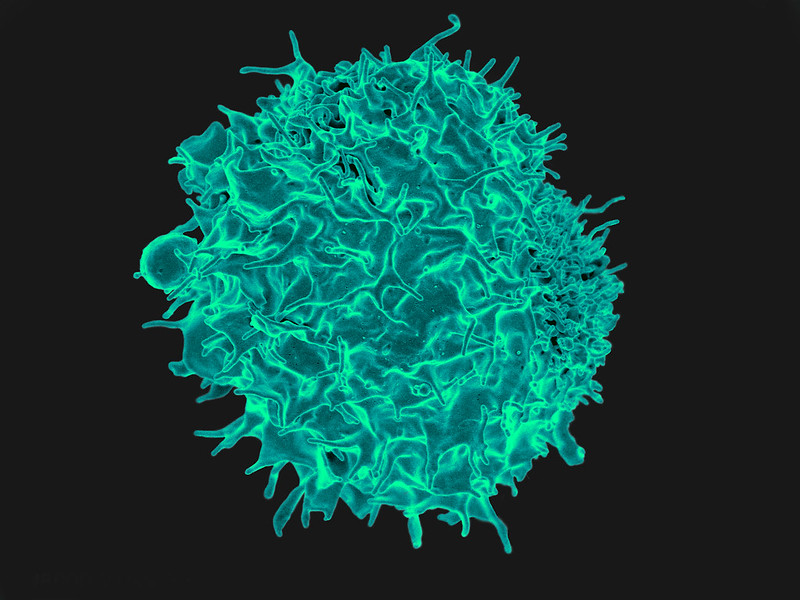

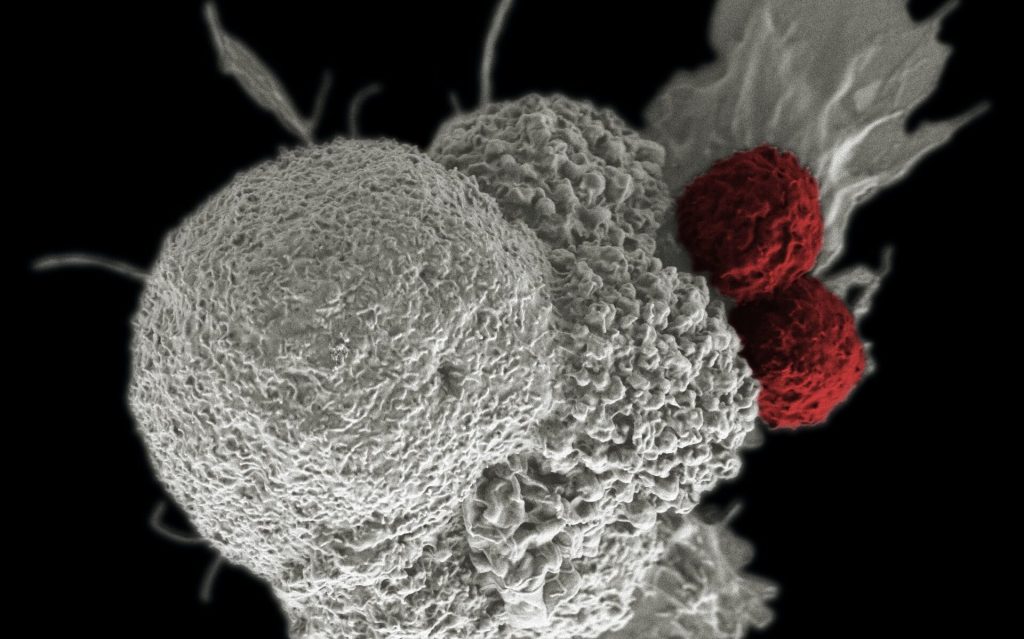

The study revolved human cells’ use of signalling and switch-flipping ions, mainly calcium. When triggered by viral proteins or allergens, T cells open channels in their outer membranes, allowing calcium in to activate signalling pathways that control cell division and secretion of cytokine molecules.

Past work had found that CRAC channels in T cells regulate their ability to multiply into armies of cells designed to fight infections caused by viruses and other pathogens.

The new study showed that the CRAC channel inhibitor reduced allergic asthma and mucus build-up in mice without undermining their immune system’s ability to fight influenza, a main worry of researchers seeking to tailor immune-suppressing drugs for several applications.

“Our study provides evidence that a new class of drugs that target CRAC channels can be used safely to counter allergic asthma without creating vulnerability to infections,” said senior study author Stefan Feske, MD, a professor at NYU Langone Health. “Systemic application of a CRAC channel blocker specifically suppressed airway inflammation in response to allergen exposure.”

Allergic asthma, which is the most common form of the disease, is characterised by increased type 2 (T2) inflammation, which involves T helper (Th) 2 cells, the study authors noted. Th2 cells produce cytokines that play important roles in both normal immune defences, and in disease-causing inflammation that occurs in the wrong place and amount. In allergic asthma, cytokines promote the production of IgE antibodies and the recruitment to the lungs of inflammation-causing immune cells called eosinophils, the hallmarks of the disease.

In the new study, the research team found that deletion of the ORAI1 protein in T cells, which makes up the CRAC channel, or treating mice with the CRAC channel inhibitor CM4620, thoroughly suppressed Th2-driven airway inflammation in response to house dust mite allergens.

Treatment with CM4620 significantly reduced airway inflammation when compared to an inactive control substance, with the treated mice also showing much lower levels of Th2 cytokines and related gene expression. Without calcium entering through CRAC channels, T cells are unable to become Th2 cells and produce the cytokines that cause allergic asthma, the authors say.

Conversely, ORAI1 gene deletion, or interfering with CRAC channel function in T cells via the study drug, did not hinder T cell-driven antiviral immunity, as lung inflammation and immune responses were similar in mice with and without ORAI1.

“Our work demonstrates that Th2 cell-mediated airway inflammation is more dependent on CRAC channels than T cell-mediated antiviral immunity in the lung,” said study co-first author Yin-Hu Wang, PhD. “This suggests CRAC channel inhibition as a promising, potential future treatment approach for allergic airway disease.”

Source: NYU Langone Health via PRNewsWire