Brains do Not Actually ‘Rewire’ Themselves, Scientists Argue

Contrary to the commonly-held view, the brain does not have the ability to rewire itself to compensate for conditions such as stroke, loss of sight or an amputation, say scientists in the journal eLife.

Professors Tamar Makin of Cambridge University and John Krakauer of Johns Hopkins University argue that the notion that the brain, in response to injury or deficit, can reorganise itself and repurpose particular regions for new functions, is fundamentally flawed – despite being commonly cited in scientific textbooks. Instead, they argue that what is occurring is merely the brain being trained to utilise already existing, but latent, abilities.

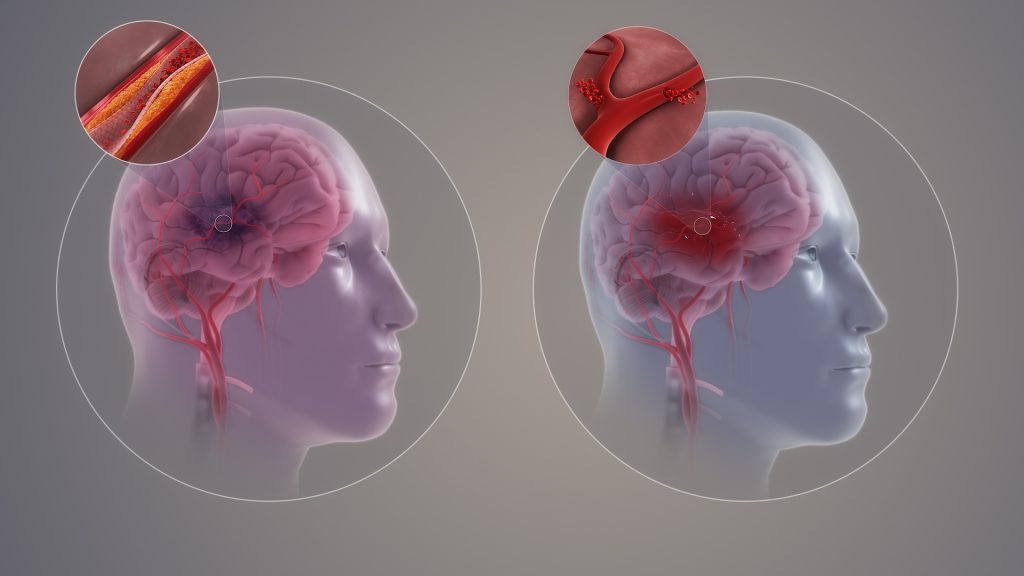

One of the most common examples given is where a person loses their sight – or is born blind – and the visual cortex, previously specialised in processing vision, is rewired to process sounds, allowing the individual to use a form of ‘echolocation’ to navigate a cluttered room. Another common example is of people who have had a stroke and are initially unable to move their limbs repurposing other areas of the brain to allow them to regain control.

Krakauer, Director of the Center for the Study of Motor Learning and Brain Repair at Johns Hopkins University, said: “The idea that our brain has an amazing ability to rewire and reorganise itself is an appealing one. It gives us hope and fascination, especially when we hear extraordinary stories of blind individuals developing almost superhuman echolocation abilities, for example, or stroke survivors miraculously regaining motor abilities they thought they’d lost.

“This idea goes beyond simple adaptation, or plasticity – it implies a wholesale repurposing of brain regions. But while these stories may well be true, the explanation of what is happening is, in fact, wrong.”

In their article, Makin and Krakauer look at a ten seminal studies that purport to show the brain’s ability to reorganise. They argue, however, that while the studies do indeed show the brain’s ability to adapt to change, it is not creating new functions in previously unrelated areas – instead it’s utilising latent capacities that have been present since birth.

For example, a 1980s study by Professor Michael Merzenich at University of California, San Francisco looked at what happens when a hand loses a finger. The hand has a particular representation in the brain, with each finger appearing to map onto a specific brain region. Remove the forefinger, and the area of the brain previously allocated to this finger is reallocated to processing signals from neighbouring fingers, argued Merzenich – in other words, the brain has rewired itself in response to changes in sensory input.

Not so, says Makin, whose own research provides an alternative explanation.

In a study published in 2022, Makin used a nerve blocker to temporarily mimic the effect of amputation of the forefinger in her subjects. She showed that even before amputation, signals from neighbouring fingers mapped onto the brain region ‘responsible’ for the forefinger — in other words, while this brain region may have been primarily responsible for process signals from the forefinger, it was not exclusively so. All that happens following amputation is that existing signals from the other fingers are ‘dialled up’ in this brain region.

Makin, from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at the University of Cambridge, said: “The brain’s ability to adapt to injury isn’t about commandeering new brain regions for entirely different purposes. These regions don’t start processing entirely new types of information. Information about the other fingers was available in the examined brain area even before the amputation, it’s just that in the original studies, the researchers didn’t pay much notice to it because it was weaker than for the finger about to be amputated.”

Another compelling counterexample to the reorganisation argument is seen in a study of congenitally deaf cats, whose auditory cortex appears to be repurposed to process vision. But when they are fitted with a cochlear implant, this brain region immediately begins processing sound once again, suggesting that the brain had not, in fact, rewired.

Examining other studies, Makin and Krakauer found no compelling evidence that the visual cortex of individuals that were born blind or the uninjured cortex of stroke survivors ever developed a novel functional ability that did not otherwise exist.

Makin and Krakauer do not dismiss stories such as blind people navigating using hearing, or individuals who have experienced a stroke regain their motor functions. They argue instead that rather than completely repurposing regions for new tasks, the brain is enhancing or modifying its pre-existing architecture — and it is doing this through repetition and learning.

Understanding the true nature and limits of brain plasticity is crucial, both for setting realistic expectations for patients and for guiding clinical practitioners in their rehabilitative approaches, they argue.

Makin added: “This learning process is a testament to the brain’s remarkable – but constrained – capacity for plasticity. There are no shortcuts or fast tracks in this journey. The idea of quickly unlocking hidden brain potentials or tapping into vast unused reserves is more wishful thinking than reality. It’s a slow, incremental journey, demanding persistent effort and practice. Recognising this helps us appreciate the hard work behind every story of recovery and adapt our strategies accordingly.

“So many times, the brain’s ability to rewire has been described as ‘miraculous’ – but we’re scientists, we don’t believe in magic. These amazing behaviours that we see are rooted in hard work, repetition and training, not the magical reassignment of the brain’s resources.”

The original text of this story is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence.

Source: University of Cambridge