New Evidence for a Chronic Disease Link with Microplastics

Tiny fragments of plastic have become ubiquitous in our environment and our bodies. Higher exposure to these microplastics, which can be inadvertently consumed or inhaled, is associated with a heightened prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases, according to new research being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session (ACC.25).

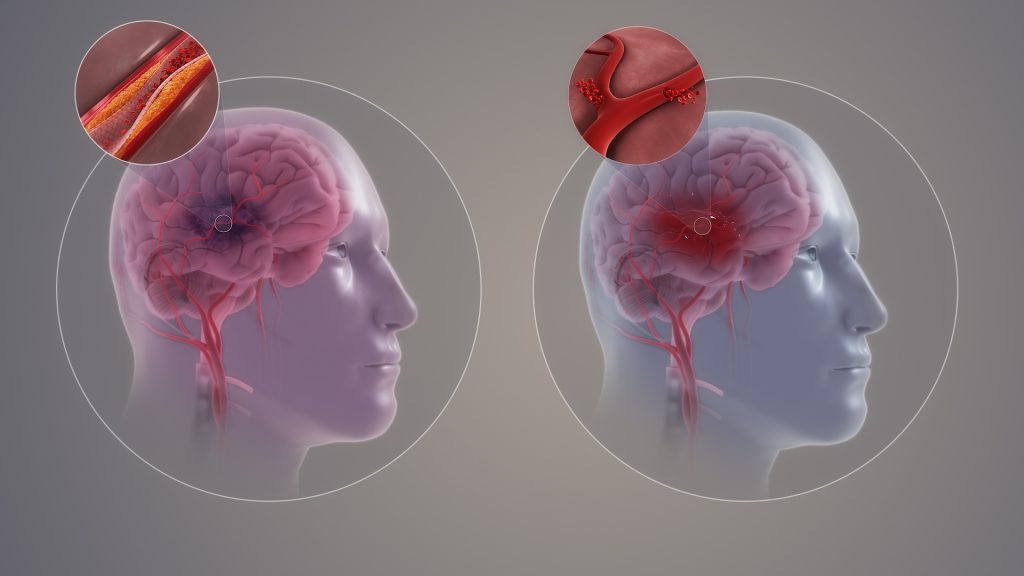

Researchers said the new findings add to a small but growing body of evidence that microplastic pollution represents an emerging health threat. In terms of its relationship with stroke risk, for example, microplastics concentration was comparable to factors such as minority race and lack of health insurance, according to the results.

“This study provides initial evidence that microplastics exposure has an impact on cardiovascular health, especially chronic, noncommunicable conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes and stroke,” said Sai Rahul Ponnana, MA, a research data scientist at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine in Ohio and the study’s lead author. “When we included 154 different socioeconomic and environmental features in our analysis, we didn’t expect microplastics to rank in the top 10 for predicting chronic noncommunicable disease prevalence.”

Microplastics—defined as fragments of plastic between 1 nanometre and 5 millimetres across—are released as larger pieces of plastic break down. They come from many different sources, such as food and beverage packaging, consumer products and building materials. People can be exposed to microplastics in the water they drink, the food they eat and the air they breathe.

The study examines associations between the concentration of microplastics in bodies of water and the prevalence of various health conditions in communities along the East, West and Gulf Coasts, as well as some lakeshores, in the United States between 2015-2019. While inland areas also contain microplastics pollution, researchers focused on lakes and coastlines because microplastics concentrations are better documented in these areas. They used a dataset covering 555 census tracts from the National Centers for Environmental Information that classified microplastics concentration in seafloor sediments as low (zero to 200 particles per square meter) to very high (over 40 000 particles per square metre).

The researchers assessed rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke and cancer in the same census tracts in 2019 using data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They also used a machine learning model to predict the prevalence of these conditions based on patterns in the data and to compare the associations observed with microplastics concentration to linkages with 154 other social and environmental factors such as median household income, employment rate and particulate matter air pollution in the same areas.

The results revealed that microplastics concentration was positively correlated with high blood pressure, diabetes and stroke, while cancer was not consistently linked with microplastics pollution. The results also suggested a dose relationship, in which higher concentrations of microplastic pollution are associated with a higher prevalence of disease. However, researchers said that evidence of an association does not necessarily mean that microplastics are causing these health problems. More studies are required to determine whether there is a causal relationship or if this pollution is occurring alongside another factor that leads to health issues, they said.

Further research is also needed to determine the amount of exposure or the length of time it might take for microplastics exposure to have an impact on health, if a causal relationship exists, according to Ponnana. Nevertheless, based on the available evidence, it is reasonable to believe that microplastics may play some role in health and we must take steps to reduce exposures, he said. While it is not feasible to completely avoid ingesting or inhaling microplastics when they are present in the environment, given how ubiquitous and tiny they are, researchers said the best way to minimise microplastics exposure is to curtail the amount of plastic produced and used, and to ensure proper disposal.

“The environment plays a very important role in our health, especially cardiovascular health,” Ponnana said. “As a result, taking care of our environment means taking care of ourselves.”

In a separate study presented at ACC.25, researchers from a different group reviewed the scientific literature and found that studies showed a strong correlation between microplastics in plaques in the heart’s arteries and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, suggesting that the presence of microplastics could play a role in the onset or exacerbation of serious heart problems.

Source: American College of Cardiology