Nanorobots Transform Stem Cells into Bone Cells with a Little Push

New method for the targeted production of specific cells

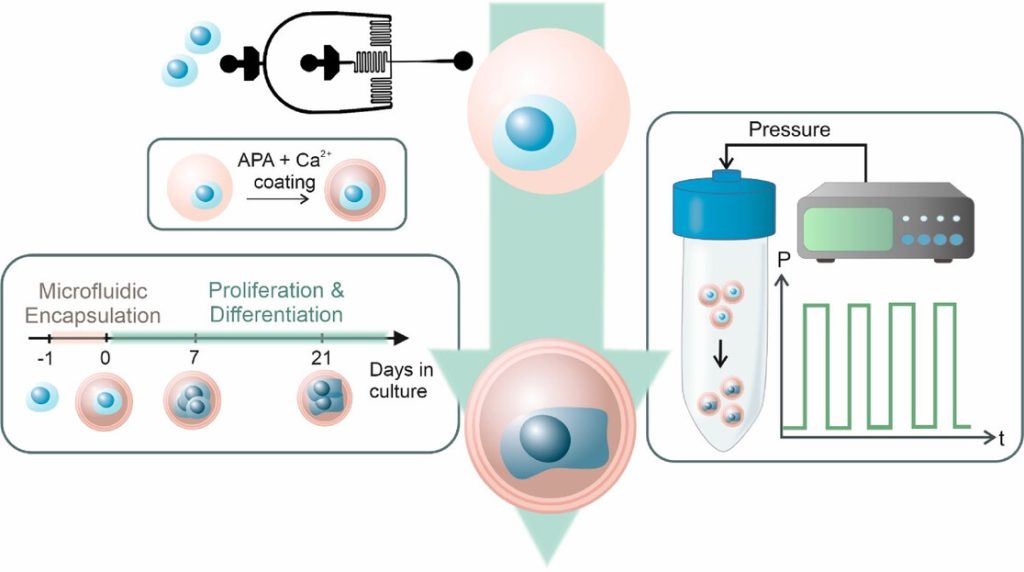

Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. MSCs (blue) were singly encapsulated using a microfluidic approach within calcium-crosslinked, RGD-functionalized alginate microgels (pink), followed by a secondary APA and calcium coating to enhance stability. Encapsulated cells were cultured for 21 days and subjected to cyclic hydrostatic pressure in regular cell culture media without any growth factors. Source: İyisan et al., Small Science, 2025.

For the first time, researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have succeeded in using nanorobots to stimulate stem cells with such precision that they are reliably transformed into bone cells. To achieve this, the robots exert external pressure on specific points in the cell wall. The new method offers opportunities for faster treatments in the future.

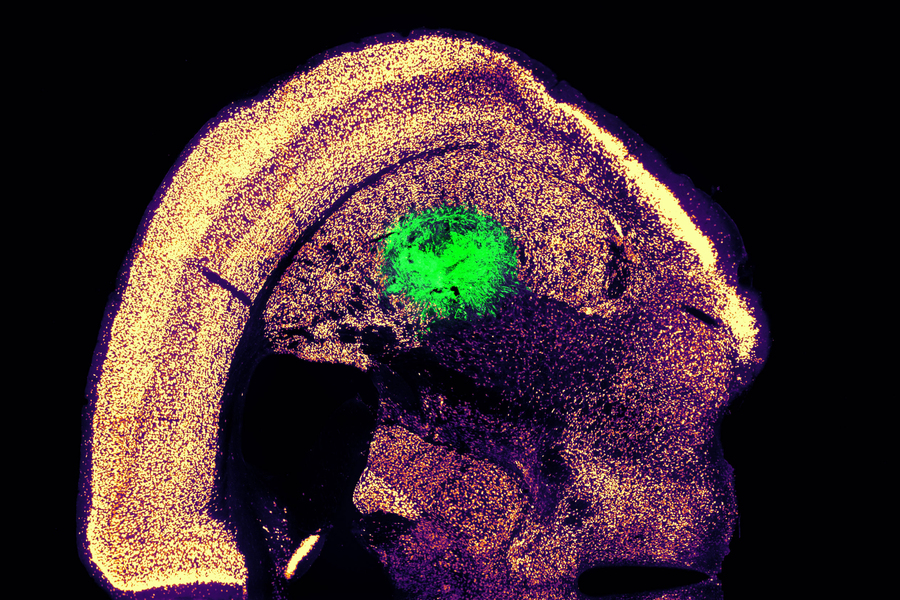

Prof Berna Özkale Edelmann’s nanorobots consist of tiny gold rods and plastic chains. Several million of them are contained in a gel cushion measuring just 60 micrometres, together with a few human stem cells. Powered and controlled by laser light, the robots, which look like tiny balls, mechanically stimulate the cells by exerting pressure. “We heat the gel locally and use our system to precisely determine the forces with which the nanorobots press on the cell – thereby stimulating it,” explains the professor of nano- and microrobotics at TUM. This mechanical stimulation triggers biochemical processes in the cell. Ion channels change their properties, and proteins are activated, including one that is particularly important for bone formation.

The research is described in Advanced Materials and Small Science.

Heart and cartilage cells: finding the correct stress pattern

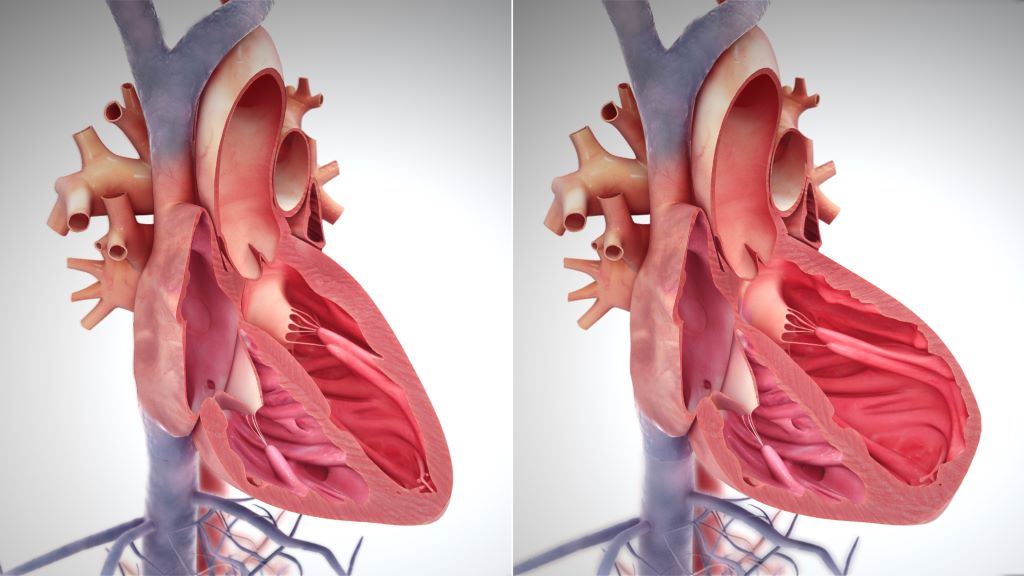

If stimulation is carried out at the right rhythm and with the right (low) force, a stem cell can be reliably triggered to develop into a bone cell within three days. This process can be completed within three weeks. “The corresponding stress pattern can also be found for cartilage and heart cells,” asserts Berna Özkale Edelman. “It’s almost like at the gym: we train the cells for a particular area of application. Now we just have to find out which stress pattern suits each cell type,” says the head of the Microbiotic Bioengineering Lab at TUM.

Mechanical forces pave the way for transformation into bone cells

The research team produces bone cells using mesenchymal stem cells. These cells are considered to be the body’s ‘repair cells’. They are approximately 10 to 20 micrometres in size and are generally capable of developing into bone, cartilage or muscle cells, for example. The challenge: The transformation into differentiated cells is complex and has been difficult to control until now. “We have developed a technology that allows forces to be applied to the cell very precisely in a three-dimensional environment,” says TUM scientist Özkale Edelmann. “This represents an unprecedented advance in the field.” The researchers believe that this method can even be used to produce cartilage and heart cells from human stem cells.

Automation is the next step

For treatments, doctors will ultimately need far more differentiated cells – around one million. “That’s why the next step is to automate our production process so that we can produce more cells more quickly,” says Prof Özkale Edelmann.

Source: Technical University Munich