Efficacy of 6-monthly HIV Prevention Jab Confirmed in Second Major Study

In June, we heard what could be this year’s biggest HIV breakthrough: a twice-yearly injection can prevent HIV infection. Findings from a second large study of the jab has now confirmed that it works. Elri Voigt goes over the new findings and unpacks the licenses that are expected to facilitate the availability of generic versions of the jab in over a hundred countries, including South Africa.

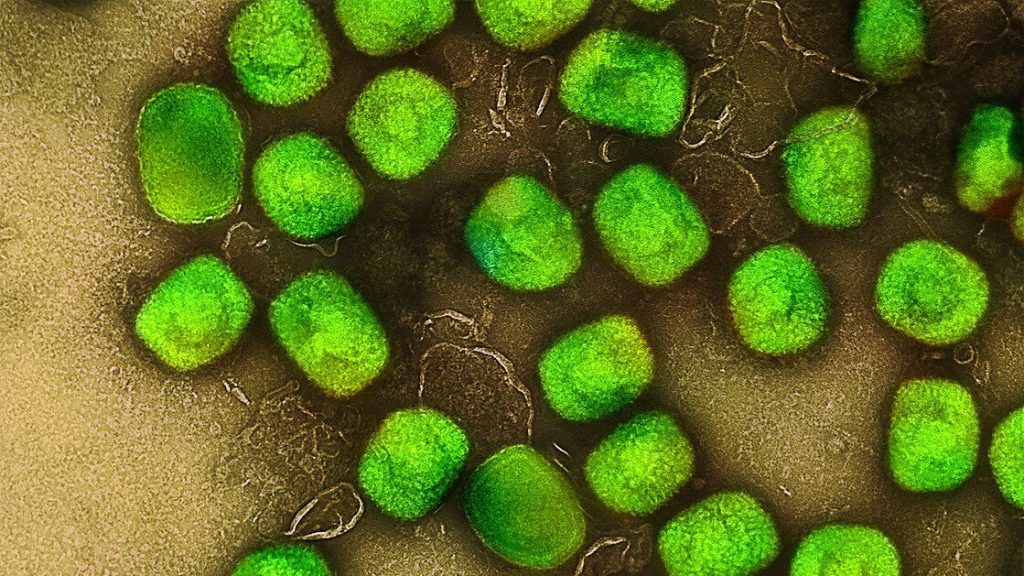

The second of two pivotal studies of a six-monthly HIV prevention injection containing the antiretroviral drug lenacapavir has confirmed that the jab works remarkably well.

The first study, called PURPOSE 1, found that the jab is safe and highly effective at preventing HIV infection in women. The second, called PURPOSE 2, found the same for cisgender men, transgender men, transgender women and non-binary people who have sex with men assigned male at birth.

Interim findings from PURPOSE 2 were presented last week at the HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P) conference in Lima, Peru.

The researchers compared the safety and efficacy of lenacapavir injections every six months to a daily HIV prevention pill – a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, called F/TDF. The results have not yet been published in a peer reviewed journal, but is expected to be soon, according to Principal Investigator for PURPOSE 2 Dr Colleen Kelley, a professor of medicine at Emory University’s School of Medicine.

The new results come hot on the heels of findings from PURPOSE 1 – previously reported on by Spotlight and published in one of the world’s top medical journals: the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the PURPOSE 1 study, none of the 2 134 people receiving the lenacapavir injection got HIV during the study. In PURPOSE 2, there were two HIV infections among the 2 179 people receiving the injection. These numbers are dramatically better than those for HIV prevention pills and for people in the communities where the study was done who were not receiving prevention injections or pills.

These findings mean the evidence is now in place for the manufacturer, Gilead Sciences, to file with regulatory authorities to register lenacapavir injections for HIV prevention. Such registration is required before the jab can be marketed for prevention. Lenacapavir injections are already registered in some countries as a last resort treatment for HIV, but not yet in South Africa.

“Now that we have a comprehensive dataset across multiple study populations, Gilead will work urgently with regulatory, government, public health and community partners to ensure that, if approved, we can deliver twice-yearly lenacapavir for PrEP worldwide, for all those who want or need PrEP,” Daniel O’Day, the chairperson and Chief Executive Officer of Gilead said in a press release. (PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, refers to taking antiretrovirals to prevent HIV infection.)

Top line findings

The interim results presented at HIVR4P by Kelley, showed that when compared to the background HIV incidence calculated in the study, lenacapavir reduced HIV infections by 96%. And when compared to the F/TDF prevention pill, the injection reduced HIV infections by 89%.

Among the 3 265 participants enrolled in the study, 11 people acquired HIV- two of the 2 179 people who were assigned to the lenacapavir arm and nine of the 1 086 participants assigned to the prevention pill arm. This translated to HIV incidence of 0.93 per 100 person years in the prevention pill arm compared to only 0.1 per 100 person years in the lenacapavir arm.

This was compared to the background incidence, which was determined when screening eligible participants for HIV. Out of 4 634 people screened for the study, 378 or 8.2% were diagnosed with HIV. Based on further laboratory testing, it was estimated that of those 378 people, 45 or 11.9% recently acquired HIV (classified as being within the last 120 days or so). This latter group provided the background HIV incidence, which was estimated to be 2.37 per 100 person years.

This is a novel study design, Kelley told Spotlight, because this calculation was used to estimate the HIV incidence that would have occurred in a placebo group without actually enrolling a placebo group.

“It’s no longer ethical to have a placebo group in HIV PrEP trials because we know that we have effective PrEP agents,” she said. “Yet, it’s almost essential to have a placebo group when you design a clinical trial so that you can really say how effective your medication, your new agent is [compared] to having nothing.”

When asked at a press conference about the two breakthrough infections in the lenacapavir arm, Kelley said the analysis for this is ongoing and will hopefully be available at a future conference and in a journal soon. She said that the two breakthrough infections in the lenacapavir arm were detected by routine testing during the study.

Kelley added that around 90% of participants in the two study arms were able to receive their injection on time. “So, we at least know that the injections were delivered in a timely fashion for almost all participants,” she said.

Whether or not the two infections occurred in people who had received the jabs on time and according to the study protocol will be closely watched as more study details is shared in the coming months.

To be enrolled in the study, participants had to meet several criteria. They had to be older than 16, never received HIV prevention injections before, weigh more than 35kg, have good kidney function, not have been tested for HIV in the last 12 weeks, and had to have been sexually active in the last 12 months.

All study participants were given a pill a day and an injection, those in the lenacapavir arm received two 1.5 ml lenacapavir injections every six months and a daily placebo pill, while those in the prevention pill arm received the daily F/TDF pill and a placebo injection every six months.

The study was conducted across seven countries, with 6 sites located in South Africa and others in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Thailand, and the United States, according to study data on Gilead’s website.

Safety data

Overall, Kelley said lenacapavir was safe and well-tolerated despite some side effects, mainly related to the injections. A total of 43 people dropped out of the study due to side effects.

The most common adverse event in the study was injection site reactions. There were more injection site reactions in the lenacapavir arm compared to the prevention pill arm. 29 people dropped out of the study because of these, 26 in the lenacapavir arm and 3 in the prevention pill arm (people in this study arm received placebo jabs).

The most common injection site reaction were subcutaneous nodules – these are harmless, usually invisible, small lumps under the skin. Nodules occur because lenacapavir is injected under the skin where it forms a drug depot. Injection site reactions and nodule size decreased with subsequent injections. This side effect and trend of decreasing reactions was also noted in the PURPOSE 1 study. Other injection site reactions were pain and erythema which is a type of skin rash.

According to Kelley, there were no serious adverse events related to injection site reactions.

When injection site reactions are excluded, according to Kelley, the other adverse events were similar across both arms, with 74% of participants in each arm experiencing an adverse event. The majority were mild or moderate.

Seven participants in each study arm dropped out due to side effects that weren’t related to injection site reactions. Those who discontinued from the lenacapavir arm will be given prevention pills for a year. This is done to protect these participants, Kelley explained, from potentially acquiring HIV when lenacapavir levels wane, as well as to reduce the risk of potential drug resistance developing.

There were a few serious adverse events, although Kelley told Spotlight she does not currently have any additional information on what these were. She explained that a serious adverse event is generally classified as something like hospitalisation, a life-threatening condition, an important medical event or adverse pregnancy outcome.

“Usually when we look at something like this, we look at the rates compared in the two arms of the study and it was 3% in the LEN [lenacapavir] arm and 4% in the F/TDF arm, so they were equal, essentially the same in both study arms,” Kelly said.

There were six deaths during the study, but none were related to the study drugs.

Next steps for lenacapavir

Now that the interim results have been announced, both studies have been unblinded and entered an open-label phase where participants have the choice of switching to or continuing with the injection.

Professor Linda-Gail Bekker, the Chief Executive Officer at the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, recently said on a webinar hosted by the South African Health Technologies Advocacy Coalition, that study participants are now able to use the PrEP option they’d prefer – either oral PrEP or the injection. This means all participants will be able to access lenacapavir through the studies if they wanted to use it.

But it will likely be a while before anyone outside of these studies can access lenacapavir as HIV prevention.

“This is an incredible intervention. Now we have to make sure everyone can get it and that’s going to be the most important next step, ensuring that everyone who needs this drug has access,” Kelley told Spotlight.

Gilead’s generic licensing agreement and pricing

What we do know so far about the next steps for lenacapavir is that the process to allow for generic manufacturing has started. This month, Gilead released its voluntary licensing agreements with six generic companies for manufacturing cheaper versions of lenacapavir.

Dr Andrew Gray, a senior lecturer in Pharmacology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, told Spotlight that no South African firms have been included in the voluntary licenses – four of the generic licensees are in India, one is in Pakistan, and one is in Egypt.

“In essence, they [the generic companies] are allowed to sell their generic versions in a number of identified countries, specified by Gilead,” Gray said. The agreement lists 120 countries, including South Africa.

Gilead itself will also be prioritising the registration of lenacapavir in 18 countries, which it said represent about 70% of the HIV burden in the countries named in the license. The list includes South Africa, Uganda, and Botswana. Gilead says it will start filing for registration with regulatory authorities by the end of the year.

It will be important to see how quickly Gilead seeks regulatory approval for lenacapavir with the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), Gray said. Registration with SAHPRA will be required before the injection can be rolled out in South Africa.

Some countries won’t be able to procure generics

Gilead received criticism for several omissions from the list of countries that the generic manufacturers can sell to. The US-based HIV advocacy group AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, among others, pointed out the exclusion of several countries which have high HIV incidence. Some of those countries participated in PURPOSE 2- namely Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Peru.

A spokesperson from Gilead told Spotlight the manufacturer’s access policy included tailored approaches to ensure rapid and broad access of lenacapavir and it objectively considered the countries where a voluntary licence would provide the most benefit.

“Gilead’s voluntary licence primarily covers countries based on economic need and HIV burden, which are primarily low- and lower-middle income countries. The voluntary licence also covers certain middle-income countries with limited access to healthcare,” the spokesperson said.

Acknowledging that some middle-income countries do have a high HIV burden, Gilead is “exploring several innovative strategies to support access to LEN for PrEP (if approved), including tiered pricing, and are working with payors to establish fast, efficient pathways to help reach people who need or want PrEP”, said the spokesperson.

“Ensuring access in middle-income and upper-middle income countries, including those in Latin America, is a priority for Gilead. Planning for these countries, incorporating input from advocates and global health organizations, is ongoing and updates will be shared as discussions progress,” the spokesperson added. “Additionally, Gilead is committed to ensuring that individuals who participated in the PURPOSE studies have been offered and will be able to stay on open label lenacapavir until it is available in their country.”

The company’s decision to license generic manufacturers directly is at odds with earlier calls from several activist groups and UNAIDS to license via the UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool.

Pricing

It will also be important to see if Gilead will disclose a single exit price for the South African market, according to Gray.

In its press release announcing the voluntary licensing agreement, Gilead stated it will “support low-cost access to the drug in high-incidence, resource-limited countries through a two-part strategy: establishing a robust voluntary licensing program and planning to provide Gilead-supplied product at no profit to Gilead until generic manufacturers are able to fully support demand”.

It is too early in the process to reveal a price for lenacapavir yet, the spokesperson from Gilead told Spotlight.

“While Gilead prepares for global regulatory filings, it is too early to disclose the price of lenacapavir for HIV prevention. Our pledge is to price our medicines to reflect the value they deliver to people, patients, healthcare systems and society. For Gilead-branded lenacapavir, we do plan to price it at no profit to Gilead in 18 select high-incidence, resource-limited countries until generic manufacturers are able to fully support demand,” the spokesperson said.

Spotlight previously reported on research that estimated that if produced at sufficient volumes, the price of lenacapavir could be drastically reduced to levels likely considered affordable by the South African government. For instance, if enough volume was produced to supply 10 million people with PrEP, the price for the injection could be as low as $40 (under R800) per person per year. At the moment, Gilead supplies lenacapavir for HIV treatment in wealthy countries for about $40 000 per person per year.

Gilead’s lenacapavir product will be the first to register in South Africa and will almost certainly be the only lenacapavir product available here for several years – that is because it is expected to take generic manufacturers a few years before they can start producing generic lenacapavir. Based on calculations made for other PrEP products, it seems unlikely that the Department of Health would be willing to procure lenacapavir at a price significantly above R1 000 per person per year. The HIV prevention pill currently costs government around R800 per person per year.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence