Inside the SAMRC’s Race to Rescue Health Research in SA

By Catherine Tomlinson

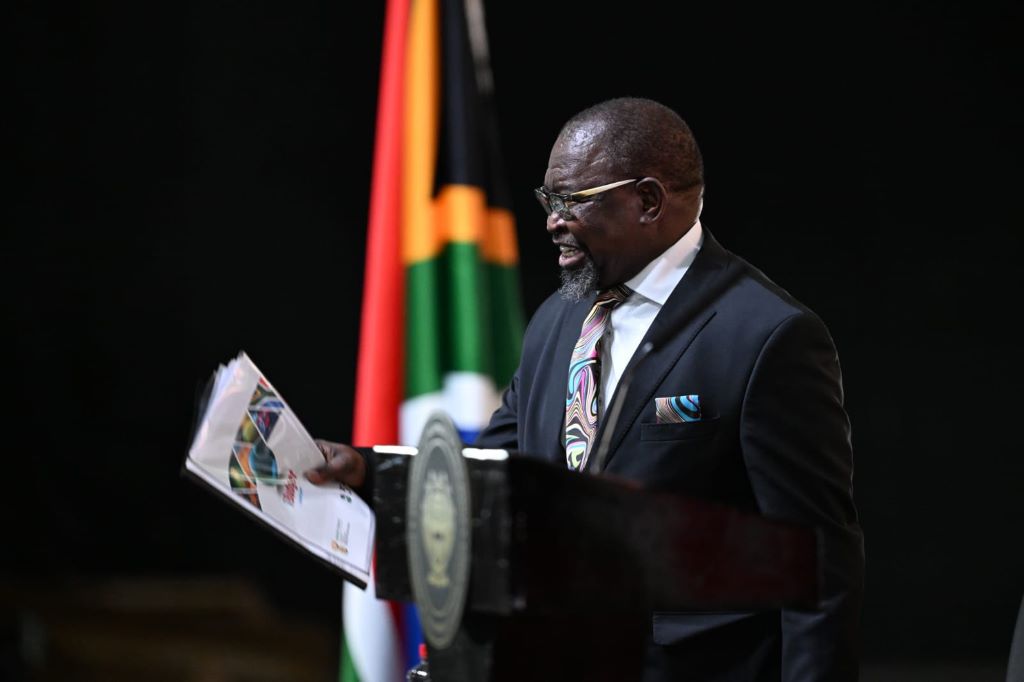

Health research in South Africa has been plunged into crisis with the abrupt termination of several large research grants from the US, with more grant terminations expected in the coming days and weeks. Professor Ntobeko Ntusi, head of the South African Medical Research Council, tells Spotlight about efforts to find alternative funding and to preserve the country’s health research capacity.

Health research in South Africa is facing an unprecedented crisis due to the termination of funding from the United States government. Though exact figures are hard to pin down, indications are that more than half of the country’s research funding has in recent years been coming from the US.

Many health research units and researchers that receive funding from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) have in recent weeks been notified that their grants have been terminated. This funding is being slashed as part of the efforts by US President Donald Trump’s administration to reduce overall federal spending and end spending that does not align with its political priorities.

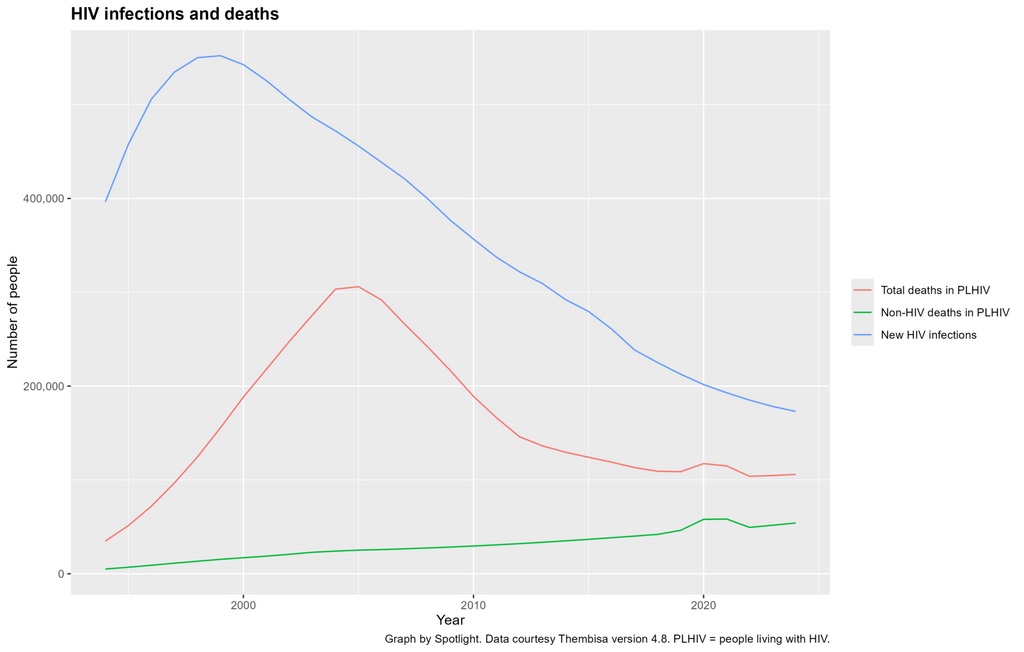

Specifically, the administration has sought to end spending supporting LGBTQ+ populations and diversity, as well as equity and inclusion. As many grants for HIV research have indicators of race, gender, and sexual orientation in their target populations and descriptions, this area of research has been particularly hard hit by the cuts. There have also been indications that certain countries, including South Africa and China, would specifically be targeted with NIH cuts.

On 7 February, President Donald Trump issued an executive order stating that the US would stop providing assistance to South Africa in part because it passed a law that allowed for the expropriation of land without compensation, and separately because the South African government took Israel to the International Court of Justice on charges of genocide in Gaza.

Prior to the NIH cuts, some local research funded through other US entities such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were also terminated.

How much money is at risk?

“In many ways the South African health research landscape has been a victim of its own success, because for decades we have been the largest recipients of both [official development assistance] funding from the US for research [and] also the largest recipients of NIH funding outside of the US,” says president and CEO of the SAMRC Professor Ntobeko Ntusi.

Determining the exact amount of research funds we get from the US is challenging. This is because funding has come from several different US government entities and distributed across various health research organisations. But the bulk of US research funding in South Africa clearly came from the NIH, which is also the largest funder of global health research.

According to Ntusi, in previous years, the NIH invested, on average, US$150 million – or almost R3 billion – into health research in South Africa every year.

By comparison, the SAMRC’s current annual allocation from government is just under R2 billion, according to Ntusi. “Our baseline funding, which is what the national treasury reflects [approximately R850 million], is what flows to us from the [Department of Health],” he says, adding that they also have “huge allocations” from the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation. (Previous Spotlight reporting quoted the R850 million figure from Treasury’s budget documents, and did not take the additional funds into account.)

How is the SAMRC tracking US funding terminations

Ntusi and his colleagues have been trying to get a clearer picture of the exact extent and potential impacts of the cuts.

While some US funding given to research units in South Africa flows through the SAMRC, the bulk goes directly to research units from international research networks, larger studies, and direct grants. Keeping track of all this is not straight-forward, but Ntusi says the SAMRC has quite up to date information on all the terminations of US research awards and grants.

“I’ve been communicating almost daily with the deputy vice-chancellors for research in all the universities, and they send me almost daily updates,” says Ntusi. He says heads of research units are also keeping him informed.

According to him, of the approximately US$150 million in annual NIH funding, “about 40%…goes to investigator-led studies with South Africans either as [principal investigators] or as sub-awardees and then the other 60% [comes from] network studies that have mostly sub-awards in South Africa”.

Figures that Ntusi shared with Spotlight show that large tertiary institutions like the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Cape Town, and the University of Stellenbosch, could in a worst case scenario lose over R200 million each, while leading research units, like the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation and the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, could each lose tens of millions. The SAMRC figures indicate that while many grants have already been terminated, there are also a substantial number that have not been terminated.

Where will new money come from?

Ntusi says the SAMRC is coordinating efforts to secure new funding to address the crisis.

“We have been leading a significant fundraising effort, which…is not for the SAMRC, but for the universities who are most affected [and] also other independent research groups,” he says. “As the custodian of health research in the country, we are looking for solutions not just for the SAMRC but for the entire health research ecosystem.”

Ntusi explains that strategically it made more sense to have a coordinated fundraising approach rather than repeating what happened during COVID-19 when various groups competed against each other and approached the same funders.

“Even though the SAMRC is leading much of this effort, there’s collective input from many stakeholders around the country,” he says, noting that his team is in regular communication with the scientific community, the Department of Health, and Department of Science, Technology and Innovation.

The SAMRC is also asking the Independent Philanthropic Association of South Africa, and large international philanthropies for new funding. He says that some individuals and philanthropies have already reached out to the SAMRC to find out how they can anonymously support research endeavours affected by the cuts.

Can government provide additional funds?

Ntusi says that the SAMRC is in discussions with National Treasury about providing additional funds to support health researchers through the funding crisis.

The editors of Spotlight and GroundUp recently called on National Treasury to commit an extra R1 billion a year to the SAMRC to prevent the devastation of health research capacity in the country. They argued that much larger allocations have previously been made to bail out struggling state-owned entities.

Government has over the last decade spent R520 billion bailing out state-owned entities and other state organs.

How will funds raised by the SAMRC be allocated?

One dilemma is that it is unlikely that all the lost funding could be replaced. This means tough decisions might have to be made about which projects are supported.

Ntusi says that the SAMRC has identified four key areas in need of support.

The first is support for post-graduate students. “There’s a large number of postgraduate students…who are on these grants” and “it’s going to be catastrophic if they all lose the opportunity to complete their PhDs,” he says.

Second is supporting young researchers who may have received their first NIH grant and rely entirely on that funding for their work and income, says Ntusi. This group is “really vulnerable [to funding terminations] and we are prioritising [their] support…to ensure that we continue to support the next generation of scientific leadership coming out of this country,” he says.

A third priority is supporting large research groups that are losing multiple sources of funding. These groups need short-term help to finish ongoing projects and to stay afloat while they apply for new grants – usually needing about 9 to 12 months of support, Ntusi explains.

The fourth priority, he says, is to raise funding to ethically end clinical and interventional studies that have lost their funding, and to make sure participants are connected to appropriate healthcare. Protecting participants is an important focus of the fundraising efforts, says Ntusi, especially since many people involved in large HIV and TB studies come from underprivileged communities.

Ultimately, he says they hope to protect health research capacity in the country to enable South African health researchers to continue to play a meaningful and leading role in their respective research fields.

“If you reflect on what I consider to be one of the greatest successes of this country, it’s been this generation of high calibre scientists who lead absolutely seminal work, and we do it across the entire value chain of research,” says Ntusi. “I would like to see…South Africa [continue to] make those meaningful and leading pioneering contributions.”

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.