Autoimmune Disease Linked to Doubling in Depression, Anxiety, Bipolar Risks

Risks higher in women than in men with the same condition

Chronic exposure to systemic inflammation may explain associations, say researchers

Living with an autoimmune disease is linked to a near doubling in the risk of persistent mental health issues, such as depression, generalised anxiety, and bipolar disorder, with these risks higher in women than in men, finds a large population-based UK study, published in the open access journal BMJ Mental Health.

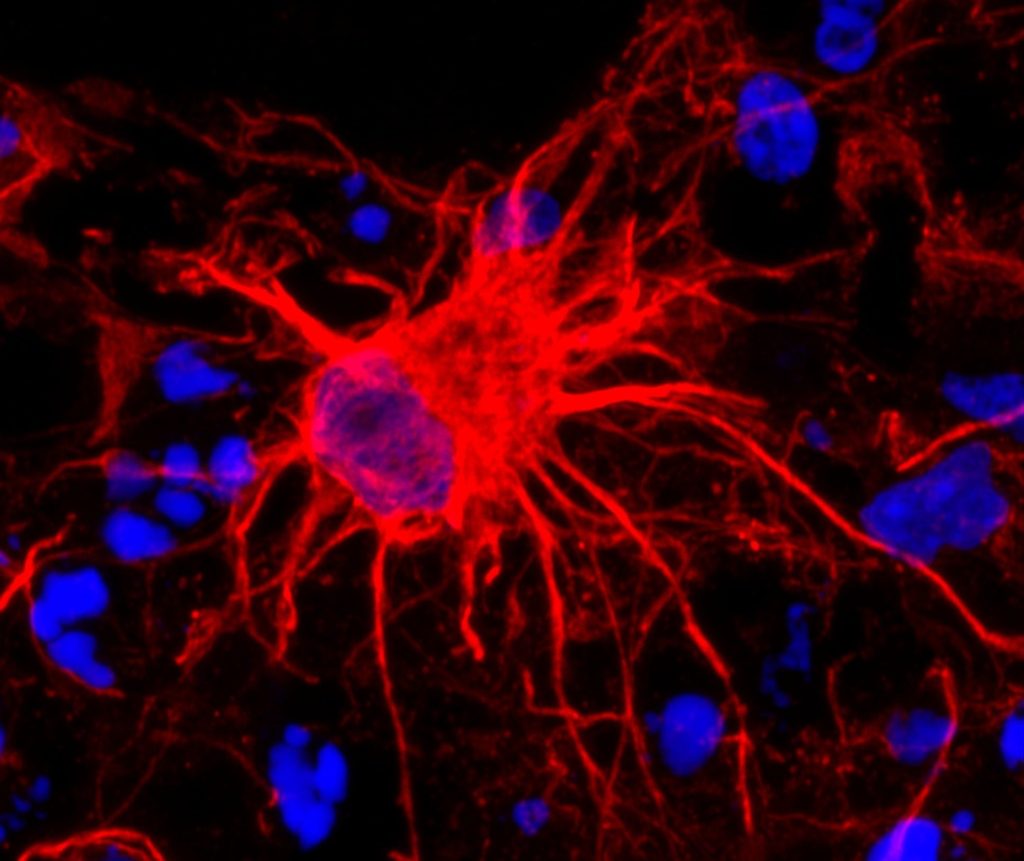

Chronic exposure to the systemic inflammation caused by the autoimmune disease may explain the associations found, say the researchers.

A growing body of evidence suggests that inflammation is linked to mental ill health, but many of the published studies have relied on small sample sizes, limiting their statistical power, note the researchers.

In a bid to overcome this, they drew on data from 1.5 million participants in the recently established Our Future Health dataset from across the UK. Participants’ average age was 53; just over half (57%) were women; and 90% identified as White.

On recruitment to Our Future Health, participants completed a baseline questionnaire to provide personal, social, demographic, health and lifestyle information.

Health information included lifetime diagnoses–including for their biological parents–for a wide range of disorders, including autoimmune and psychiatric conditions.

Six autoimmune conditions were included in the study: rheumatoid arthritis; Graves’ syndrome (thyroid hormone disorder); inflammatory bowel disease; lupus, multiple sclerosis; and psoriasis.

The mental health conditions of interest were self-reported diagnoses of affective disorders, defined as depression, bipolar, or anxiety disorder.

In all, 37 808 participants reported autoimmune conditions and 1 525 347 didn’t. Those with autoimmune conditions were more likely to be women (74.5% vs 56.5%) and more likely to report lifetime diagnoses of affective disorders for their biological parents: 8% vs 5.5% for fathers; 15.5% vs 11% for mothers.

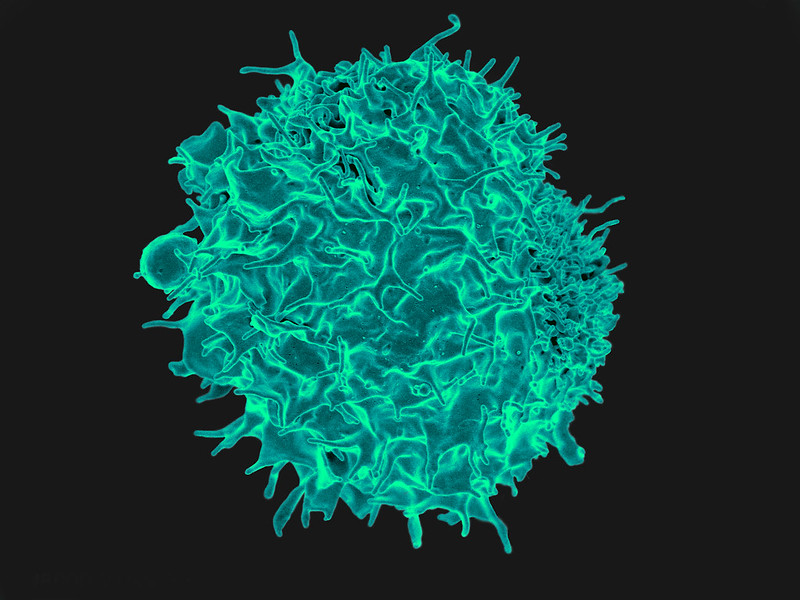

Chronic and pathogenic immune system activation—including the presence of markers of inflammation—is a hallmark of many autoimmune conditions. And in the absence of direct measurements of inflammatory biomarkers, an autoimmune condition was regarded as a proxy for chronic inflammation in this study.

The lifetime prevalence of any diagnosed affective disorder was significantly higher among people with an autoimmune disorder than it was among the general population: 29% vs 18%.

Similar associations in lifetime prevalence emerged for depression and anxiety: 25.5% vs just over 15% for depression; and just over 21% vs 12.5% for anxiety.

While the overall prevalence of bipolar disorder was much lower, it was still significantly higher among those with an autoimmune disorder than it was among the general population: just under 1% compared with 0.5%.

The prevalence of current depression and anxiety was also higher among people with autoimmune conditions.

And the prevalence of affective disorders was significantly and consistently higher among women than it was among men with the same physical health conditions: 32% compared to 21% among participants with any autoimmune disorder.

The reasons for this aren’t clear, say the researchers, but “theories suggest that sex hormones, chromosomal factors, and differences in circulating antibodies may partly explain these sex differences,” they write.

“Women (but not men) with depression exhibit increased concentrations of circulating cytokines and acute phase reactants compared with non-depressed counterparts. It is therefore possible that women may experience the compounding challenges of increased occurrence of autoimmunity and stronger effects of immune responses on mental health, resulting in the substantially higher prevalence of affective disorders observed in this study,” they add.

Overall, the risk for each of the affective disorders was nearly twice as high—87-97% higher—in people with autoimmune conditions, and remained high even after adjusting for potentially influential factors, including age, household income, and parental psychiatric history.

No information was available on the time or duration of illness, making it impossible to determine whether autoimmune conditions preceded, co-occurred with, or followed, affective disorders, note the researchers.

No direct measurements of inflammation were made either, and it was therefore impossible to establish the presence, nature, timing or severity of inflammation, they add.

“Although the observational design of this study does not allow for direct inference of causal mechanisms, this analysis of a large national dataset suggests that chronic exposure to systemic inflammation may be linked to a greater risk for affective disorder,” they conclude.

“Future studies should seek to determine whether putative biological, psychological, and social factors—for example, chronic pain, fatigue, sleep or circadian disruptions and social isolation—may represent potentially modifiable mechanisms linking autoimmune conditions and affective disorders.”

And they suggest that it may be worth regularly screening people diagnosed with autoimmune disease for mental health conditions, especially women, to provide them with tailored treatment early on.

Source: BMJ