Study Reveals Association Between Semaglutide Use and Optic Neuropathy

Researchers from Mass Eye and Ear have discovered an association between semaglutide use and an increased risk of nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION) in patients with type 2 diabetes, overweight or obesity. The findings, which appear in JAMA Ophthalmology, only show an association and cannot establish causation.

Though NAION is relatively rare, occurring in in about 10 in 100 000, it is the second most common cause of optic nerve blindness, behind glaucoma, and it is the most common cause of sudden optic nerve blindness. Caused by decreased blood flow to the optic disc, it usually affects only one eye but in 15% of cases both eyes are involved. There are no treatments for this disease and little prospect for improvement, although it is painless.

The study was led by Joseph Rizzo, MD, director of the Neuro-Ophthalmology Service at Mass Eye and Ear and the Simmons Lessell Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School.

In mid-2023 Rizzo, a resident (study co-author Seyedeh Maryam Zekavat, MD, PhD) and other Mass Eye and Ear neuro-ophthalmologists noticed a disturbing trend – three patients in their practice had been diagnosed with vision loss from this relatively uncommon optic nerve disease in just one week. They did notice however that all three were taking semaglutide.

“The use of these drugs has exploded throughout industrialised countries and they have provided very significant benefits in many ways, but future discussions between a patient and their physician should include NAION as a potential risk,” said Rizzo, corresponding author of the study. “It is important to appreciate, however, that the increased risk relates to a disorder that is relatively uncommon.”

This prompted the Mass Eye and Ear research team to run a retrospective analysis of their patient population to see if they could identify a link between this disease and these drugs.

They performed matched cohort study of 16 827 patients revealed higher risk of NAION in patients prescribed semaglutide compared with patients prescribed non–GLP-1 receptor agonist medications for diabetes or obesity.

The researchers found that patients with diabetes who were prescribed and took semaglutide were four times (hazard ratio [HR], 4.28) more likely to be receive a NAION diagnosis. The odds increased to more than seven times (HR, 7.64) when the prescription was for weight control in obesity.

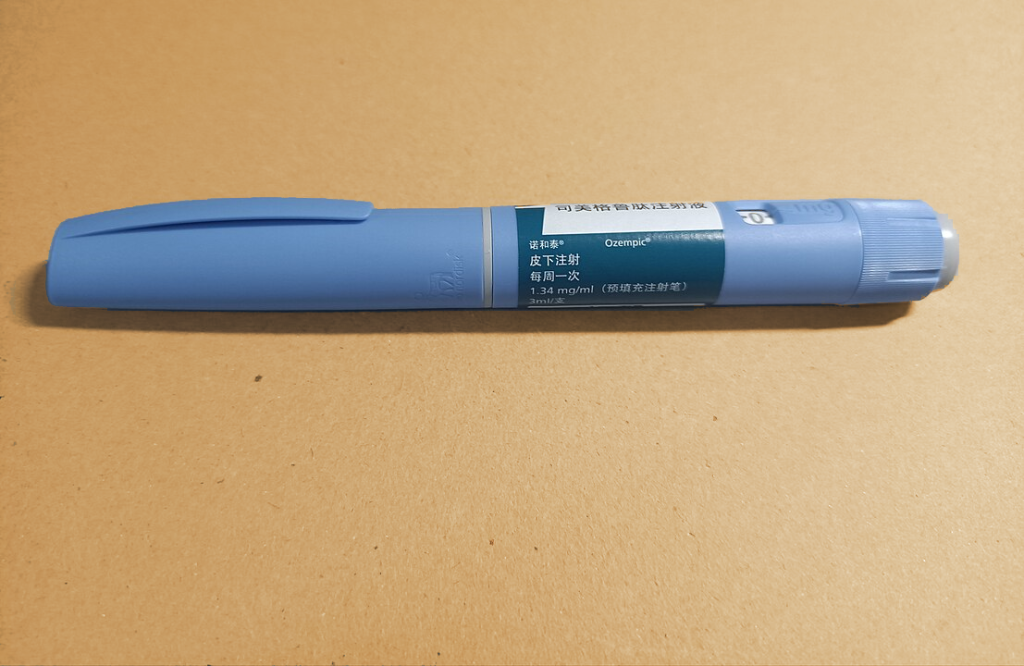

The researchers analysed the records of more than 17 000 Mass Eye and Ear patients treated over the six years since Ozempic was released and divided the patients in those who were diagnosed with either diabetes or overweight/ obesity. The researchers compared patients who had received prescriptions for semaglutide compared to those taking other diabetes or weight loss drugs. Then, they analysed the rate of NAION diagnoses in the groups, which revealed the significant risk increases.

Study limitations include the fact that Mass Eye and Ear sees an unusually high number of people with rare eye diseases, and the number of NAION cases seen over the six-year study period is relatively small. With small case numbers, statistics can change quickly, Rizzo noted. Medication adherence could also not be assessed.

Only correlation can be shown by the study, not causality. How or why this association exists remains unknown. Likewise, the reason for the reported difference between diabetic and overweight groups – but this does not appear to result from a difference in baseline characteristics. The optic nerve is known to host GLP-1 receptors, but the study did not adequately address all the confounding factors. They also caution against generalising the results (from a majority white population) since Black individuals have a lower risk of NAION.

“Our findings should be viewed as being significant but tentative, as future studies are needed to examine these questions in a much larger and more diverse population,” Rizzo said. “This is information we did not have before and it should be included in discussions between patients and their doctors, especially if patients have other known optic nerve problems like glaucoma or if there is pre-existing significant visual loss from other causes.”