Oestrogen and Progesterone Stimulate the Body to Make Opioids

Female hormones can suppress pain by making immune cells near the spinal cord produce opioids, a new study from researchers at UC San Francisco has found. This stops pain signals before they get to the brain.

The discovery could help with developing new treatments for chronic pain. It may explain why some painkillers work better for women than men and why postmenopausal women, whose bodies produce less of the key hormones oestrogen and progesterone, experience more pain.

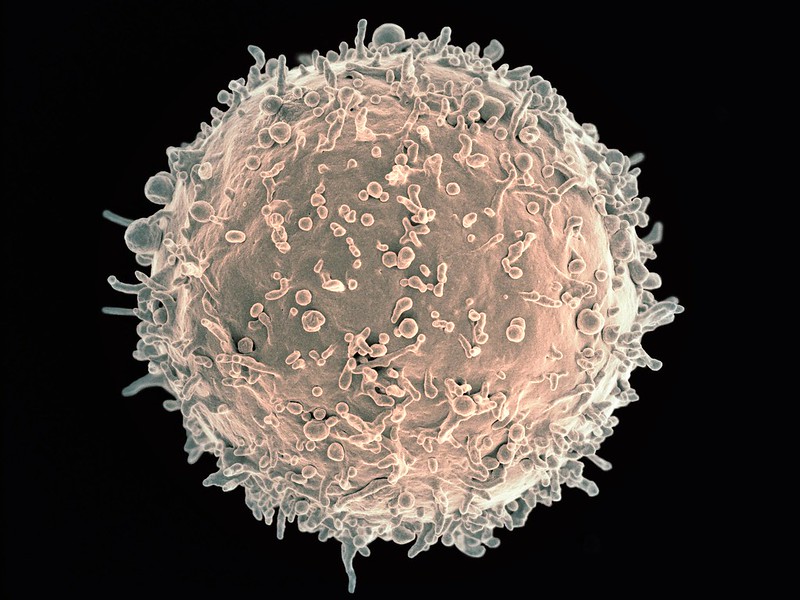

The work reveals an entirely new role for T regulatory immune cells (T-regs), which are known for their ability to reduce inflammation.

“The fact that there’s a sex-dependent influence on these cells – driven by oestrogen and progesterone – and that it’s not related at all to any immune function is very unusual,” said Elora Midavaine, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow and first author of the study, which appears in Science.

The researchers looked at T-regs in the protective layers that encase the brain and spinal cord in mice. Until now, scientists thought these tissue layers, called the meninges, only served to protect the central nervous system and eliminate waste. T-regs were only discovered there in recent years.

“What we are showing now is that the immune system actually uses the meninges to communicate with distant neurons that detect sensation on the skin,” said Sakeen Kashem, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of dermatology. “This is something we hadn’t known before.”

That communication begins when a neuron, often near the skin, receives a stimulus and sends a signal to the spinal cord.

The team found that the meninges surrounding the lower part of the spinal cord harbour an abundance of T-regs. To learn what their function was, the researchers knocked the cells out with a toxin.

The effect was striking: Without the T-regs, female mice became more sensitive to pain, while male mice did not. This sex-specific difference suggested that female mice rely more on T-regs to manage pain.

“It was both fascinating and puzzling,” said Kashem, who co-led the study with Allan Basbaum, PhD. “It actually made me sceptical initially.”

Further experiments revealed a relationship between T-regs and female hormones that no one had seen before: Estrogen and progesterone were prompting the cells to churn out enkephalin, a naturally occurring opioid.

Exactly how the hormones do this is a question the team hopes to answer in a future study. But even without that understanding, the awareness of this sex-dependent pathway is likely to lead to much-needed new approaches for treating pain.

In the short run, it may help physicians choose medications that could be more effective for a patient, depending on their sex. Certain migraine treatments, for example, are known to work better on women than men.

This could be particularly helpful for women who have gone through menopause and no longer produce oestrogen and progesterone, many of whom experience chronic pain.

The researchers have begun looking into the possibility of engineering T-regs to produce enkephalin on a constant basis in both men and women.