‘Synbiotic’ Offers Superior Anti-inflammatory Benefits to Omega-3 or Prebiotic Alone

A new study, led by experts at the University of Nottingham, has found that combining certain types of dietary supplements is more effective than single prebiotics or omega-3 in supporting immune and metabolic health, which could lower the risk of conditions linked to chronic inflammation.

The findings of the study, which are published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, show that a synbiotic – a combination of naturally fermented kefir and a diverse prebiotic fibre mix – produces the most powerful anti-inflammatory effects among the three common dietary supplements tested.

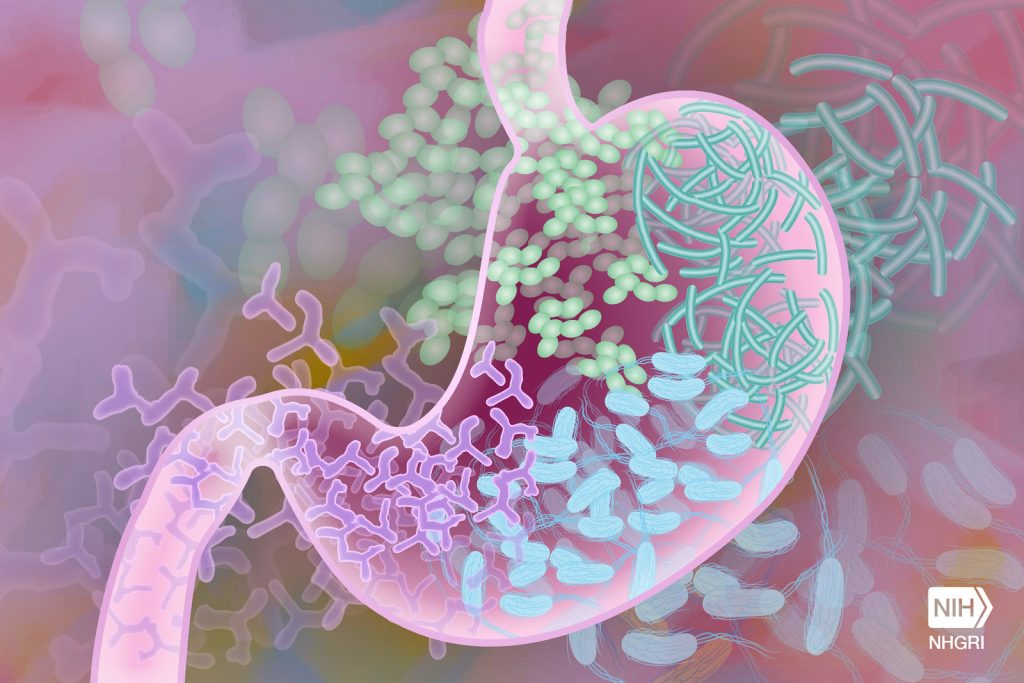

The kefir and prebiotic mix contains a mx of naturally occurring probiotic bacteria and yeasts, which form during the traditional fermentation of goat’s milk with live kefir grains. These grains are living cultures that house dozens of beneficial microbial species.

When you combine kefir (rich in live beneficial microbes) with a diverse prebiotic fibre (which feeds them), there is a synbiotic effect – the fibre nourishes the microbes, helping them thrive and produce beneficial metabolites like butyrate, which has anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects throughout the body.

Over six weeks, healthy participants taking the synbiotic saw the broadest reduction in inflammation-related proteins compared to those taking omega-3 or fibre alone. The findings suggest that pairing beneficial microbes with prebiotic fibre could help support immune and metabolic health more effectively than single supplements.

Systemic inflammatory markers are signals in the blood that show how much inflammation is happening throughout the body, not just in one specific area like the gut or an infection. The findings of the study showed that the participants’ overall levels of inflammation across their whole body went down, suggesting an improvement in general immune balance and lower risk for conditions linked to chronic inflammation (like heart disease or other metabolic conditions).

The next stage of the research would be to test the supplements on people with certain conditions to see the effectiveness.

The study was led by Dr Amrita Vijay in the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham.

Our study shows that while all three dietary approaches reduced inflammation, the synbiotic – combining fermented kefir with a diverse prebiotic fibre mix – had the most powerful and wide-ranging effects. This suggests that the interaction between beneficial microbes and dietary fibre may be key to supporting immune balance and metabolic health.

Dr Amrita Vijay

Source: University of Nottingham