The Gut Microbiome can Affect Symptoms of Hypopituitarism

In research published in PLOS Genetics, scientists have shown that the balance of bacteria in the gut can influence symptoms of hypopituitarism in mice. They also showed that aspirin was able to improve hormone deficiency symptoms in mice with this condition.

People with mutations in a gene called Sox3 develop hypopituitarism, where the pituitary gland doesn’t make enough hormones. It can result in growth problems, infertility and poor responses of the body to stress.

The scientists at the at the Francis Crick Institute removed Sox3 from mice, causing them to develop hypopituitarism around the time of weaning (starting to eat solid food).

They found that mutations in Sox3 largely affect the hypothalamus in the brain, which instructs the pituitary gland to release hormones. However, the gene is normally active in several brain cell types, so the first task was to ask which specific cells were most affected by its absence.

The scientists observed a reduced number of cells called NG2 glia, suggesting that these play a critical role in inducing the pituitary gland cells to mature around weaning, which was not known previously. This could explain the associated impact on hormone production.

The team then treated the mice with a low dose of aspirin for 21 days. This caused the number of NG2 glia in the hypothalamus to increase and reversed the symptoms of hypopituitarism in the mice.

Although it’s not yet clear how aspirin had this effect, the findings suggest that it could be explored as a potential treatment for people with Sox3 mutations or other situations where the NG2 glia are compromised.

An incidental discovery revealed the role of gut bacteria in hormone production

When the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) merged with the Crick in 2015, mouse embryos were transferred from the former building to the latter, and this included the mice with Sox3 mutations.

When these mice reached the weaning stage at the Crick, the researchers were surprised to find that they no longer had the expected hormonal deficiencies.

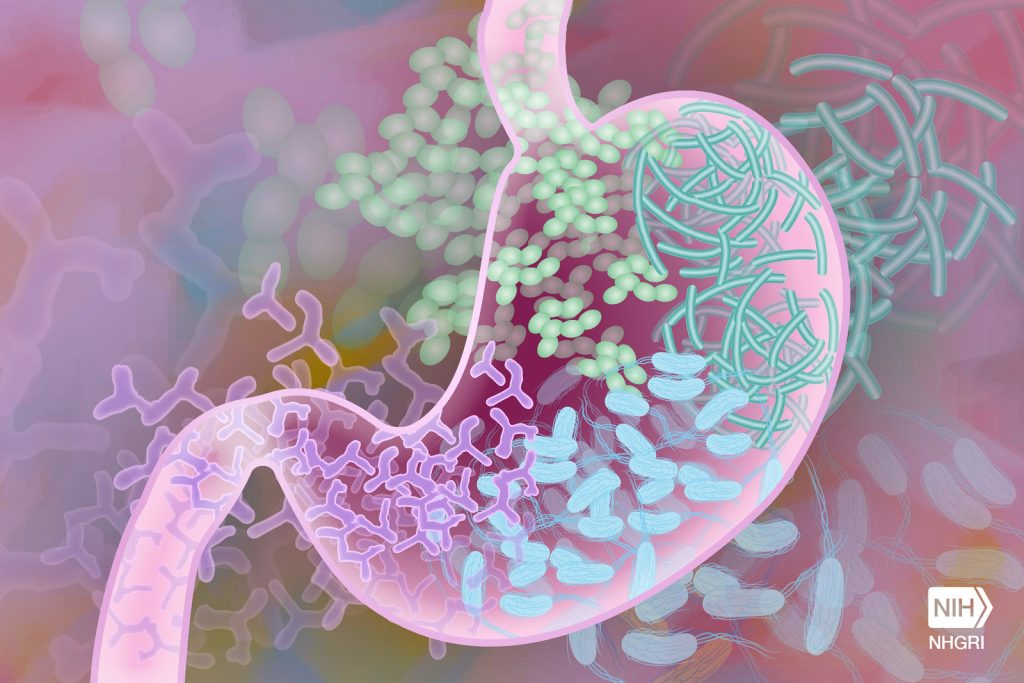

After exploring a number of possible causes, lead author Christophe Galichet compared the microbiome – bacteria, fungi and viruses that live in the gut – in the mice from the Crick and mice from the NIMR, observing several differences in its makeup and diversity. This could have been due to the change in diet, water environment, or other factors that accompanied the relocation.

He also examined the number of NG2 glia in the Crick mice, finding that these were also at normal levels, suggesting that the Crick-fed microbiome was somehow protective against hypopituitarism.

To confirm this theory, Christophe transplanted faecal matter retained from NIMR mice into Crick mice, observing that the Crick mice once again showed symptoms of hypopituitarism and had lower numbers of NG2 glia.

Although the exact mechanism is unknown, the scientists conclude that the make-up of the gut microbiome is an example of an important environmental factor having a significant influence on the consequences of a genetic mutation, in this case influencing the function of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.

Source: Francis Crick Institute