Semaglutide Cuts CVD Events by 20% in People with Obesity or Overweight but not Diabetes

In a large, international clinical trial, people with obesity or overweight but not diabetes taking semaglutide for more than three years had a 20% lower risk of cardiovascular disease outcomes and lost an average of 9.4% of their body weight.

Semaglutide, a GLP-1 medication primarily prescribed for people with Type 2 diabetes, is also FDA-approved for weight loss in people with obesity.

These results were shared in a late-breaking science presentation at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 and the full manuscript was also published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“This news is very encouraging for people with overweight or obesity because no treatment specifically directed at the management of obesity and overweight in people without Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes has been tested in a randomised trial and been shown to influence cardiovascular outcomes,” said lead study author A. Michael Lincoff, MD.

While prior research has confirmed the benefits of semaglutide in managing blood sugar, decreasing cardiovascular disease events and reducing weight in people with Type 2 diabetes, this study specifically investigated the potential impact of semaglutide on cardiovascular disease in people with overweight or obesity and cardiovascular disease who did not have either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

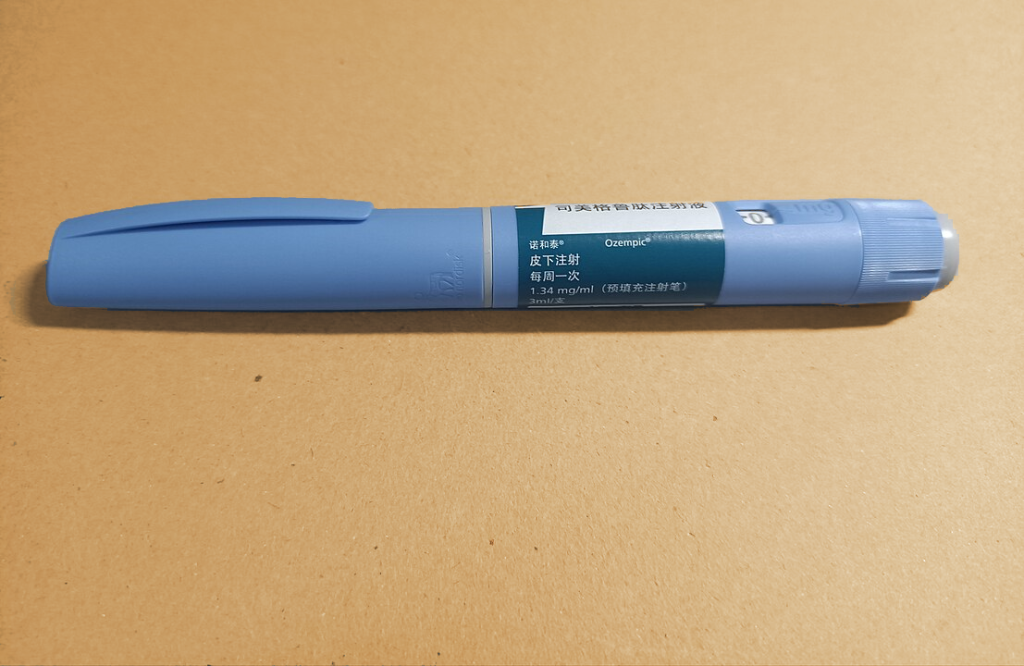

In this randomised, controlled, double-blind trial, participants were assigned to take either 2.4mg of semaglutide (the FDA-approved semaglutide dose for weight management) or a placebo once a week, which is higher than the FDA-approved semaglutide dose limit for Type 2 diabetes of 2.0mg/week. Each person in the study used a ‘pen’ to inject the medicine or placebo into a skin fold in their stomach, thigh or upper arm each week on the same day, and the dose started at 0.24mg and gradually increased every four weeks up to 2.4mg, and mean follow-up for all participants was 40 months.

In addition to taking either semaglutide or placebo for the trial, all participants also received standard of care treatment for cardiovascular disease, such as cholesterol modifying medications, antiplatelet therapies, beta blockers or other treatments. The authors note that heart disease diagnoses varied among the participants, therefore, treatment was adjusted to meet each individual’s diagnosis and needs, as well as the treatment guidelines in their country of residence.

The study, which ran from October 2018 through June 2023, indicated the following:

- There was a 20% reduction in the risk of heart attacks, strokes or death due to cardiovascular disease in the participants who took semaglutide, compared to the participants in the placebo group.

- In the semaglutide group, the participants’ body weight was reduced, on average, by 9.4% compared to a reduction of 0.9% among the adults in the placebo group.

- There were no new safety concerns found in the study, which researchers note is encouraging since the SELECT trial is the largest and longest (4.5 years) trial of semaglutide in adults without Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

- The number of serious adverse events was lower in the semaglutide group. Previous studies of medications of the GLP-1 receptor agonist class have shown an association with gallbladder disorders, and in SELECT, there was a slightly higher rate of gallbladder disorders in the semaglutide vs placebo group (2.8% vs 2.3%, respectively).

- Semaglutide was stopped more frequently than placebo for gastrointestinal intolerance, a known side effect of this class of medications; however, there was no higher rate of serious gastrointestinal events.

- The researchers noted that this medication did not lead to an increased rate of pancreatitis, which has been a concern with prior medications of this type.

- Of note, other weight-loss medications that are not GLP-1 receptor agonists have been associated with increased risks of psychiatric disorders or cancer; these risks were not elevated with semaglutide in the SELECT trial.

“It’s been estimated that within about ten years, over half of the world’s population will have overweight or obesity,” said Dr Lincoff. “And while GLP-1 medications are frequently prescribed for patients with vascular disease and Type 2 diabetes, there is a significant number of people who do not have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes but do have vascular disease and overweight or obesity for whom these medications are often not available due to access to care issues, insurance coverage or other factors. This population may now potentially benefit from semaglutide, and importantly, our results indicate the magnitude of cardiovascular risk reduction with semaglutide among people without Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes is the same as what we have seen in people with Type 2 diabetes. Our findings expand the opportunity to treat patients who have overweight or obesity and existing heart disease without Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, and we have a chance to significantly reduce their risk of a secondary cardiovascular event including death.”

Among the study limitations were including adults with prior cardiovascular disease, thereby not investigating primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (people with no history of a heart attack, stroke and/or peripheral artery disease). In addition, 28% of the study participants were female, which is not proportionate to the number of women with cardiovascular disease and overweight or obesity in the general population.

Additional analyses will include identifying the mediators of the cardiovascular benefit to determine to what extent the results were driven by reduction of metabolically unhealthy body fat, positive impacts on inflammation or blood sugar, direct effects of the medication itself on plaque build-up in the arteries, or a combination of one or more variables.

Source: American Heart Association