FDA-Approved Drug Halts EBV-Driven Lymphoma by Disrupting a Key Cancer Pathway

Scientists at The Wistar Institute have discovered that a class of FDA-approved cancer drugs known as PARP1 inhibitors can effectively combat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-driven lymphomas. The findings, published in the Journal of Medical Virology, demonstrate that these drugs, which work by blocking the activity of the PARP1 enzyme, can halt tumour growth by interfering with the EBV’s ability to activate key cancer-promoting genes.

“We’ve uncovered a completely different mechanism for how PARP inhibitors work in EBV-positive cancers,” said Italo Tempera, PhD, associate professor at Wistar’s Ellen and Ronald Caplan Cancer Center and senior author of the study. “Instead of preventing DNA damage from repairing itself in the tumours, like these drugs do in other cancers, they essentially cut off the virus’s ability to hijack cellular machinery to drive cancer growth. This opens up exciting possibilities for repurposing existing FDA-approved drugs to treat EBV-associated cancers.”

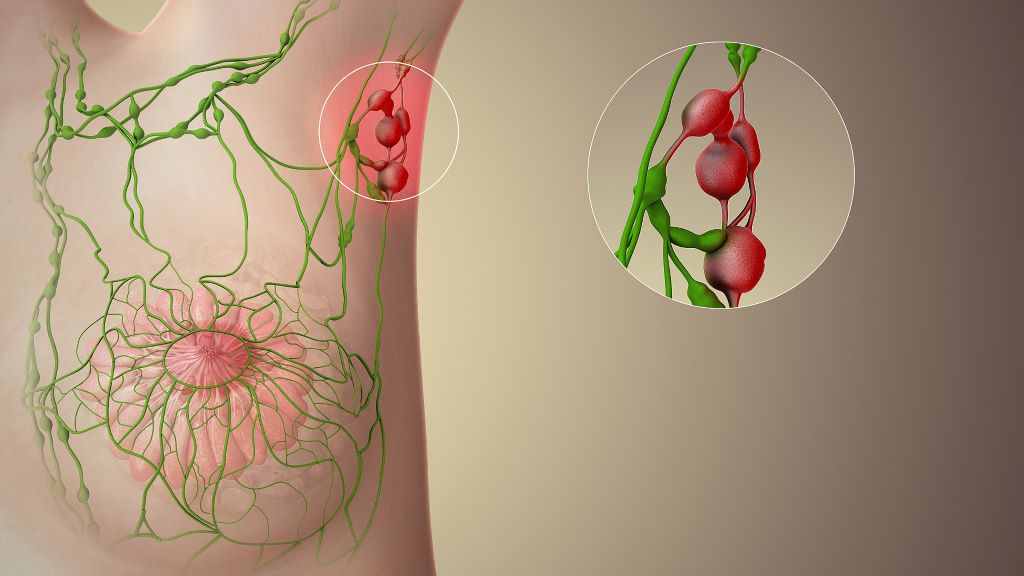

EBV infects over 90% of the global population. While most people with the virus remain symptom-free, immunocompromised individuals such as people with HIV and transplant recipients have an increased risk of EBV causing several types of cancer, including various lymphomas and carcinomas. Despite the virus’s clear role in driving these malignancies, no specific therapies currently target EBV-driven cancer.

In search of such a therapy, Tempera and his research team focused on PARP1, a cellular protein that is known primarily for its role in DNA repair. In cancer treatment, PARP inhibitors typically work by preventing cancer cells from repairing their DNA, causing them to die. However, Tempera’s team had previously discovered that PARP1 plays a very different role in EBV infection: It helps control which genes are accessible and active, essentially acting as a master regulator of gene expression.

“Think of PARP1 as a key that opens up DNA to make certain genes readable,” explained Tempera. “EBV uses this key to unlock cancer-promoting genes. When we block PARP1, we’re essentially taking away the key so the virus can’t get in and use our DNA for its own purposes.”

Using a mouse model of EBV-driven lymphoma, the researchers treated the animals with BMN 673 (talazoparib/talzenna), a PARP inhibitor that has already been approved for breast cancer treatment. Compared to controls, the treated mice showed an 80% reduction in tumour growth, and the cancer’s ability to spread to other organs was significantly reduced. Further, when the team analysed the tumours, they found no increase in DNA damage in the treated animals – the hallmark of how PARP inhibitors typically work. Instead, they discovered that PARP1 inhibition disrupted a critical partnership between the viral protein EBNA2 and the cellular oncogene MYC.

“EBNA2 is like the conductor of an orchestra, directing cellular genes to play a cancer symphony,” said Tempera. “It specifically turns on MYC, which is one of the most important cancer-promoting genes. When we inhibit PARP1, EBNA2 can’t effectively activate MYC anymore, and the whole cancer program falls apart.”

The findings have significant therapeutic implications. Because PARP inhibitors are already FDA-approved and their safety profiles are well established, the path to clinical application could be accelerated compared to developing entirely new drugs.

The research also suggests this approach might work beyond EBV-associated lymphomas. The team is now investigating whether PARP inhibitors could be effective against other EBV-driven cancers, including nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinomas. Additionally, given EBV’s suspected role in autoimmune diseases, the researchers are exploring whether PARP1’s regulation of viral gene expression might contribute to these conditions.

“This work really showcases the power of understanding fundamental viral biology,” said Tempera. “We’re taking insights from basic virology research and translating them into potential therapies. With further development, this approach could provide new hope for patients with EBV-associated cancers who currently have limited treatment options.”

Source: Wistar Institute