NICD Issues Lassa Fever Alert over KZN Case

The National Institute for Communicable diseases has reported that a case of Lassa fever was diagnosed in a man from KwaZulu-Natal on 12 May 2022. The man had extensive travel history in Nigeria before returning to South Africa. He fell ill after entering South Africa and was hospitalised in a Pietermaritzburg hospital. The diagnosis of Lassa fever was confirmed by lab tests. Sadly, the man succumbed to the infection.

Contact tracing and monitoring is underway. No secondary cases of Lassa fever have been confirmed at the time of this report. In February 2022, three cases of Lassa fever had been reported in the UK, with the first travelling from Mali and the other two resulting from secondary transmission.

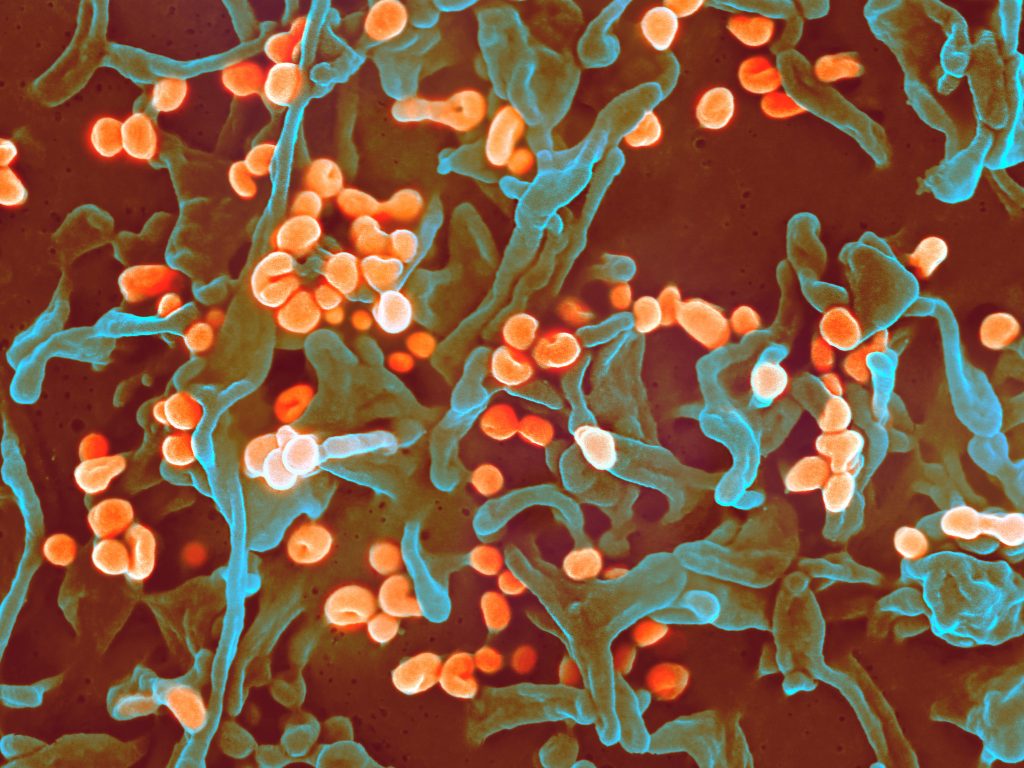

Originally discovered in 1969, Lassa fever is a rodentborne viral haemorrhagic fever endemic to West African countries and is caused by Lassa virus. Up to 300 000 cases of Lassa fever, with about 5000 deaths, are recorded annually in the endemic countries. Currently there is no vaccine for Lassa fever. The clinical course of Lassa fever is either not recognised or mild in 80% of patients; however, about 20% of patients might experience severe disease, including facial swelling, hepatic and renal abnormalities, pulmonary oedema, and haemorrhage. Although overall case-fatality rates for patients with Lassa fever is about 1%, rates among hospitalised case-patients are >15%. Intravenous administration of the antiviral drug ribavirin has become the standard of care for treatment of Lassa fever, but data on the efficacy of intravenous ribavirin are limited. The original study among Lassa fever patients in Sierra Leone found survival to be significantly higher (p = 0.0002) among those who obtained ribavirin within the first 6 days of illness (55%) compared with those who never received the drug (5%).

The natural reservoir of this virus in endemic countries is the Mastomys rat. The rats are persistently infected, shedding the virus in their urine and faeces. Humans can come into contact with the virus through direct contact or inhalation of the virus in areas that are infested with the infected rats. For example, contact with contaminated materials, ingestion of contaminated food or inhalation of air that has been contaminated with urine droplets. Person-to-person transmission of the virus does not occur readily and the virus is not spread through casual contact.

Person-to-person transmission is not common and is mostly associated with the hospital-setting where healthcare workers have contact with the infected blood and bodily fluids of a patient. Cases of Lassa fever in travellers returning from endemic countries are reported from time-to-time. In 2007 a case of Lassa fever was diagnosed in South Africa. That case involved a Nigerian citizen with extensive travel history in rural parts of Nigeria before falling ill, and he received medical treatment in South Africa. There were no reported secondary cases of Lassa fever on this occasion. Recently, in February 2022, an imported case of Lassa fever with secondary cases were identified in the United Kingdom.

Source: NICD