Nerve Stimulation Fails When the Brain is not ‘Listening’

Various diseases can be treated by stimulating the vagus nerve in the ear with electrical signals, but the results can be ‘hit or miss’. A study recently published in Frontiers in Physiology has now shown that the electrical signals must be synchronised with the body’s natural rhythms – heartbeat and breathing.

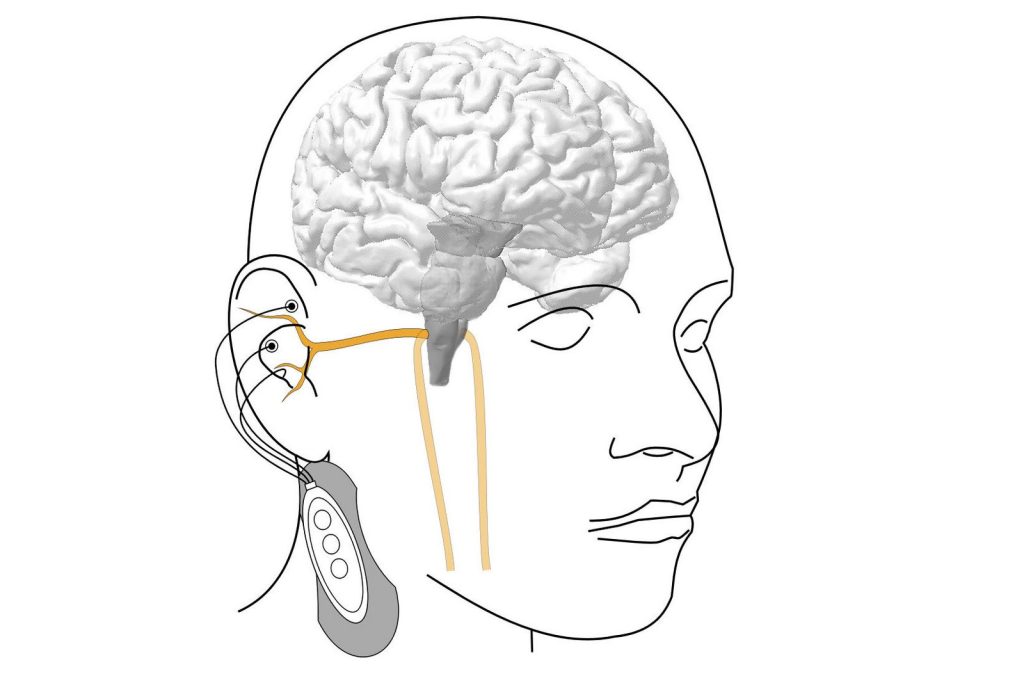

Some health problems, from chronic pain and inflammation to neurological diseases, can also be treated by nerve stimulation, for example with the help of electrodes that are attached to the ear and activate the vagus nerve. This method is sometimes referred to as an ‘electric pill’.

However, vagus nerve stimulation does not always work the way it is supposed to. A study conducted by TU Wien (Vienna) in cooperation with the Vienna Private Clinic now shows how this can be improved: Experiments demonstrate that the effect is very good when the electrical stimulation is synchronised with the body’s natural rhythms – the actual heartbeat and breathing.

The ‘electric pill’ for the parasympathetic nervous system

The vagus nerve plays an important role in our body: it is the longest nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system, the part of the nervous system that is significantly involved in the precise control of the internal organs and blood circulation, and is responsible for recovery and building up the body’s own reserves. A branch of the vagus nerve also leads from the brain directly into the ear, which is why small electrodes in the ear can be used to activate the vagus nerve, stimulate the brain and thus influence various functions of the body.

“However, it turns out that this stimulation does not always produce the expected results,” says Prof Eugenijus Kaniusas from the Institute of Biomedical Electronics at TU Wien. “The electrical stimulation does not have an effect on the nervous system at all times. You could say that the brain is just not always listening. It’s as if there is a gate to the control centre of the nervous system that is sometimes open and then closed again, and this can change in less than a second.”

Five people have now been examined in a pilot study. Their vagus nerve was electrically activated to lower their heart rate. It is already known from previous studies that heart rate is a potential indicator of whether stimulation therapy is beneficial or not.

It was shown that the temporal connection between the stimulation and the heartbeat plays a decisive role. If the vagus nerve is stimulated at a rhythm that is not synchronised with the heartbeat, hardly any effect can be observed. However, if the stimulation signals are always applied when the heart is contracting (during systole), a strong effect can be observed – much stronger than if stimulation is applied during the relaxation phase of the heart, diastole.

Breathing is also important in this context: the stimulation was significantly more effective during the inhalation phase than during the exhalation phase.

“Our results show that synchronising vagus nerve stimulation with the heartbeat and breathing rhythm significantly increases effectiveness. This could help to improve the success of treatment for chronic illnesses, especially for those who have not previously responded to this therapy for reasons that are as yet unexplained,” says Eugenijus Kaniusas.

Larger clinical studies to follow

If nerve stimulation can be customised electronically so that it is tailored to the body’s own individual rhythms at any given time, it should be possible to achieve significantly greater successes than has been possible to date. Future studies should examine larger and clinically relevant patient groups and develop even more precise algorithms in order to be able to tailor the stimulation even more precisely to individual needs.

“This technology could be an effective and non-invasive way of modulating the autonomic nervous system in a targeted and gentle manner – a potential milestone in the neuromodulatory treatment of various chronic diseases,” believes Dr Joszef Constantin Szeles from the Vienna Private Clinic.

Source: Vienna University of Technology