Debunking Myths About Mpox

Myths are widely held beliefs about various issues, including illness and disease. They come about through frequent storytelling and retelling. Dr Themba Hadebe, Clinical Executive at Bonitas Medical Fund, helps debunks myths about monkeypox (mpox).

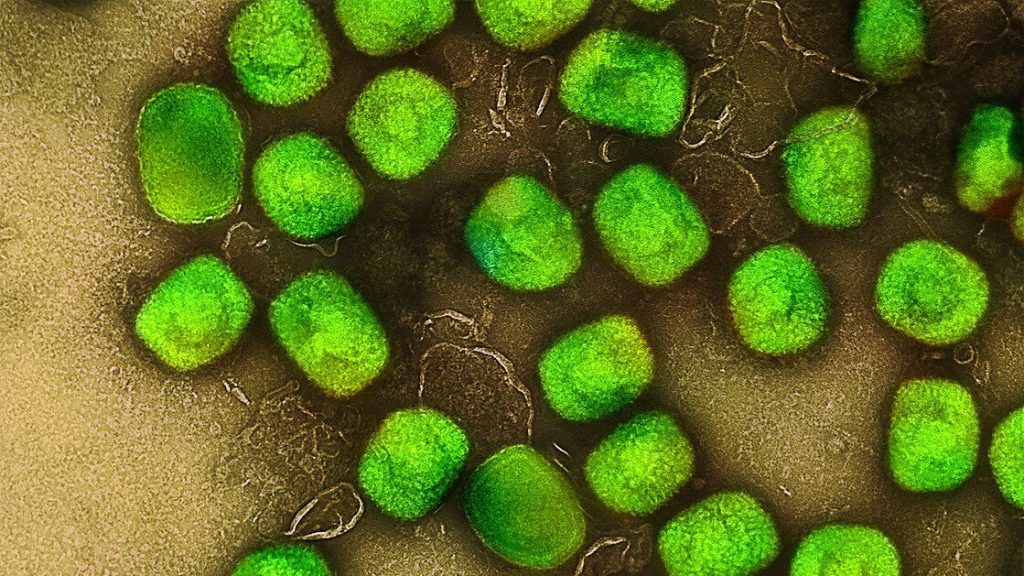

Myth 1: Mpox (formerly monkeypox) is a new disease created in a lab

Fact: The mpox virus was discovered in Denmark (1958) in a colony of monkeys at a laboratory kept for research. The first reported human case was in 1970 in the DRC. Mpox is a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be spread between animals and people. It is found regularly in parts of Central and West Africa and can spread from person to person or occasionally from animals to people.

Myth 2: Mpox comes from monkeys

Fact: Despite its name, monkeypox does not come from monkeys. The disease earned the name when the ‘pox like’ outbreaks happened in the research monkeys. While monkeys can get mpox, they are not the reservoir (where a disease typically grows and multiplies). The reservoir appears to be rodents.

Myth 3: Only a handful of people have contracted mpox

Fact: Globally, more than 97 000 cases and 186 deaths were reported across 117 countries in the first four months of 2024. South Africa is among the countries currently experiencing an outbreak. On the 5 July, it was reported that the number of mpox cases in the country has risen to 20. This after four more cases have been confirmed in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal in the last few days.

15 patients have, however been given a clean bill of health.

Myth 4: It is easy to diagnose mpox

Fact: It is easy to mistake mpox for something else. While the rash can be mistaken for chickenpox, shingles or herpes, there are differences between these rashes. Symptoms of mpox include fever, sore throat, headache, muscle aches, back pain, low energy and swollen lymph nodes. Fever, muscle aches and a sore throat appear first. The rash begins on the face and spreads over the body, extending to the palms of the hands and soles of the feet and develops over 2-4 weeks in stages. The ‘pox’ dip in the centre before crusting over.

Laboratory confirmation is required. A sample of one of the sores is diagnosed by a PCR test for the virus (MPXV).

Myth 5: Mpox is easily treated

Fact: ‘Currently,’ says the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), ‘there is no registered treatment for mpox in South Africa. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of TPOXX for treatment of severe cases, in immunocompromised people’. However, the Department of Health (DoH) has only obtained this treatment, with approval on a compassionate use basis, for the five known patients with severe disease.

There is no mpox vaccine currently available in South Africa.

Myth 6: You can get mpox from being in a crowd or from a public toilet seat

Fact: Mpox is not like Covid-19 which is highly contagious. It spreads through direct contact via blood, bodily fluid, skin or mucous lesions or respiratory droplets.

It can also spread though bites and scratches. Studies have shown that the virus can stay on surfaces but it is not spreading in that way or in a public setting. The risk of airborne transmission appears low.

Myth 7: Mpox is deadly

Fact: While mpox lesions can look similar to smallpox lesions, mpox infections are much milder and are rarely fatal. That said, symptoms can be severe in some patients, needing hospitalisation and, in rare cases, result in death. It is, however, painful and very unpleasant. So, it is important to avoid infection.

Myth 8: Mpox is sexually transmitted

Fact: You can become infected though close, direct contact with the lesions, rash, scabs or certain bodily fluids of someone who has mpox. Even though this could imply transmission though sexual activity, it is not limited to that. You can also be exposed if you are in close physical proximity to infected people, such as spouses or young children who sleep in the same bed.

Myth 9: I can’t protect myself from getting Mpox

Fact: You can take precautions: Avoid handling clothes, sheets, blankets or other materials that have been in contact with an infected animal or person. Wash your hands well with soap and water after any contact with an infected person or animal and clean and disinfect surfaces. Practice safe sex and use personal protective equipment (PPE) when caring for someone infected with the virus.

Myth 10: You can’t stop other people being infected by you

Fact: You may not protect them by 100% but you can isolate. Also, alert people who have had recent contact with you. Wash your hands regularly with soap and water or use hand sanitiser, especially before or after touching sore and disinfected shared spaces. Cover lesions when around other people, keep skin dry and uncovered (unless in a room with someone else).

Mpox is a notifiable medical condition but is treatable, if you are concerned, call the DoH toll free number of 0800 029 999 but remember, your GP is your first port of call for all your healthcare needs.