How to Stop Melanoma’s Incredibly Swift Evasion of Treatment

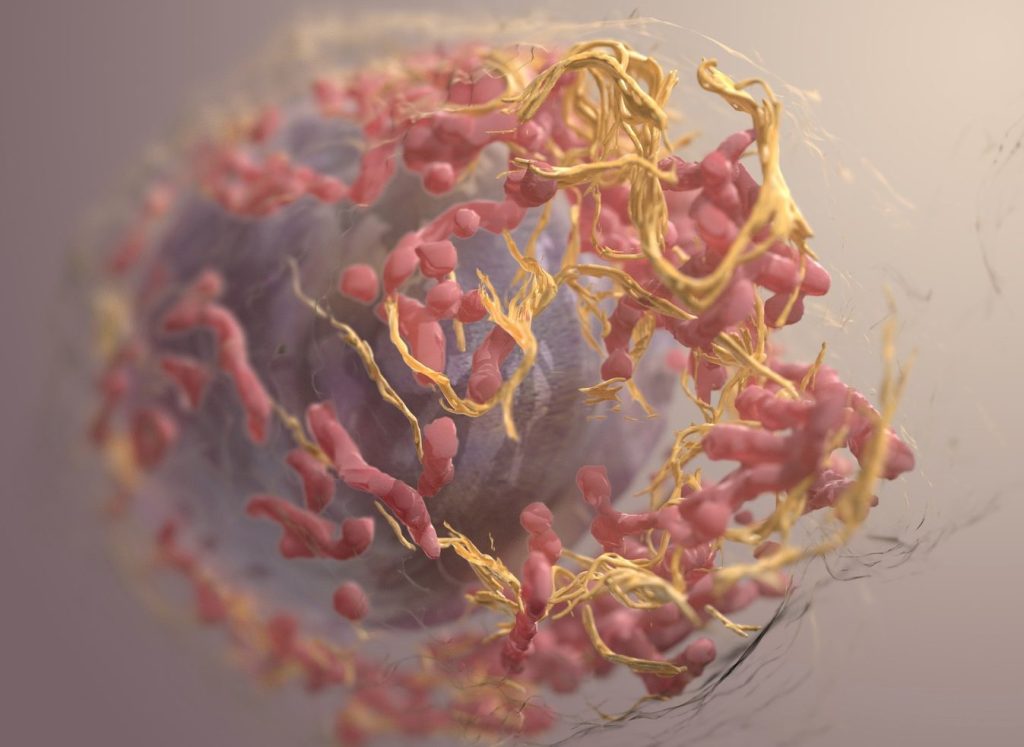

Researchers have uncovered a stealth survival strategy that melanoma cells use to evade targeted therapy, offering a promising new approach to improving treatment outcomes.

The study, published in Cell Systems and conducted by researchers at the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) identifies a non-genetic, reversible adaptation mechanism that allows melanoma cells to survive treatment with BRAF inhibitors. By identifying and blocking this early response, researchers proposed a combination therapy that could delay resistance and enhance the effectiveness of existing treatments.

Cracking the Code of Melanoma’s Drug Escape

Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is often driven by mutations in the BRAF gene, which fuels uncontrolled tumor growth. While BRAF inhibitors (such as vemurafenib) initially halt tumor growth, many tumors quickly adapt and survive treatment, leading to therapy failure.

Unlike traditional resistance driven by genetic mutations, this study uncovers an early, dynamic adaptation process that occurs within hours to days of drug treatment – long before genetic resistance takes hold. Surprisingly, this process does not rely on reactivating the BRAF-ERK pathway, which is the usual resistance mechanism.

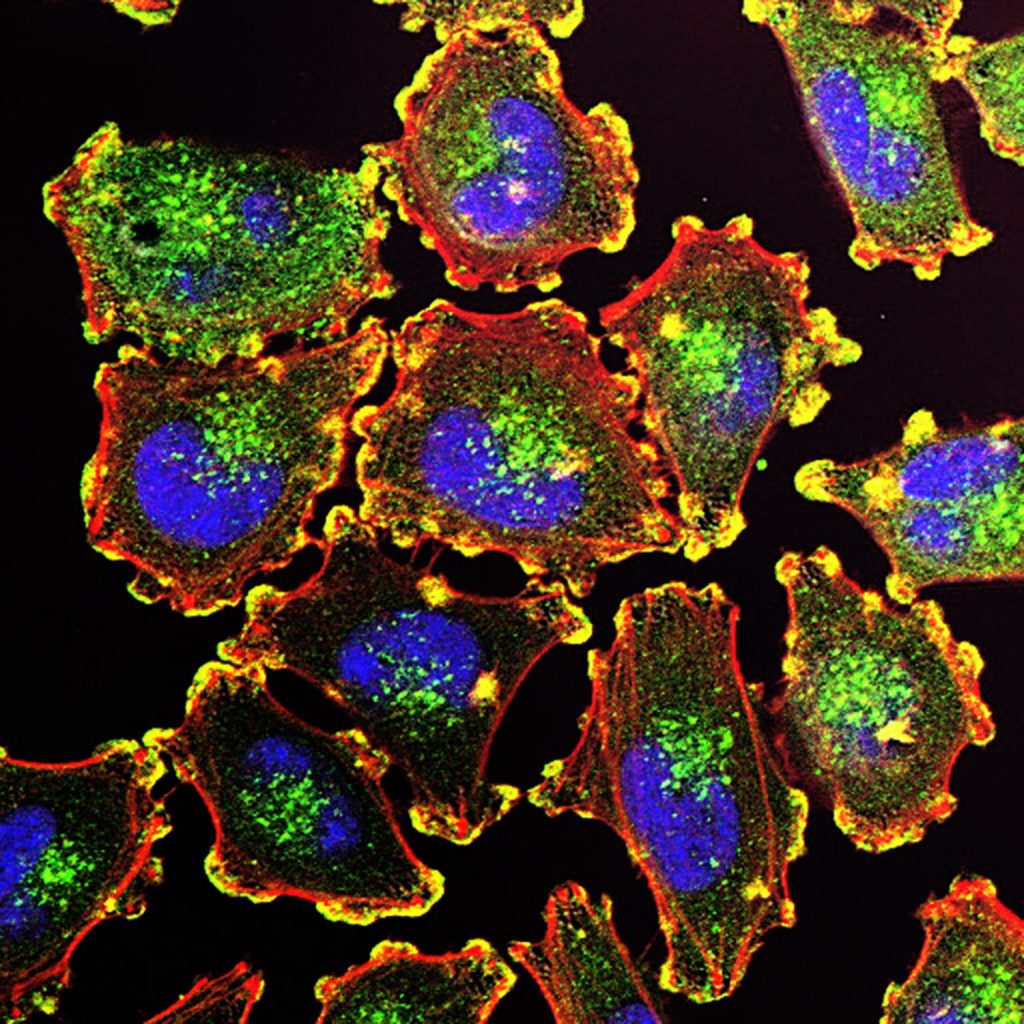

Using cutting-edge mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomics and deep transcriptomics analyses, researchers mapped the molecular shifts in melanoma cells over minutes, hours, and days of BRAF inhibitor treatment.

“We found that while the BRAF-ERK signaling pathway was quickly and durably suppressed, cancer cells did not rely on reactivating ERK to survive. Instead, they triggered an alternative SRC family kinase (SFK) signaling pathway, which promoted cell survival and eventual recovery,” said Chunmei Liu, PhD, a bioinformatics scientist at ISB and co-first author of the paper.

Turning a Weakness Into a Target

A key discovery in this study came when researchers linked SFK activation to reactive oxygen species (ROS), a cellular stress response that builds up under BRAF inhibition. As ROS levels surged, SFK activity spiked, helping melanoma cells withstand treatment. However, this adaptation was reversible – when treatment was removed, cells returned to their original state.

Recognizing this Achilles’ heel, the team tested a combination approach: pairing BRAF inhibitors with the SFK inhibitor dasatinib.

“By adding dasatinib, we blocked this adaptive escape mechanism, significantly reducing melanoma cell survival and stabilising tumours in animal models,” said ISB Associate Professor Wei Wei, PhD, co-corresponding author.

Importantly, SFK inhibition alone had little effect on melanoma cells, highlighting the need for a strategic combination therapy to suppress melanoma adaptation before resistance fully develops.

“This approach has the potential to prolong the effectiveness of BRAF inhibitors and improve patient outcomes,” said ISB President and Professor Jim Heath, PhD, co-corresponding author.

Looking Ahead: A Path to the Clinic

Beyond uncovering a key mechanism of drug adaptation, this research underscores the importance of early intervention to prevent it from happening. It also highlights ROS accumulation and SFK activation as potential biomarkers for identifying patients who may benefit from this combination therapy.

Further preclinical studies and clinical trials will be necessary to validate this combination therapy strategy and determine its potential for broader clinical use.

Source: Institute for Systems Biology