Pilot IBS Study Suggests Mediterranean Diet May be an Alternative to Low FODMAP

A pilot study from Michigan Medicine researchers found that the Mediterranean diet may provide symptom relief for people with irritable bowel syndrome. For the study, which was published in Neurogastroenterology & Motility, participants were randomised into two groups, one following the Mediterranean diet and the other following the low FODMAP diet, a common restrictive diet for IBS.

In the Mediterranean diet group, 73% of the patients met the primary endpoint for symptom improvement, versus 81.8% in the low FODMAP group.

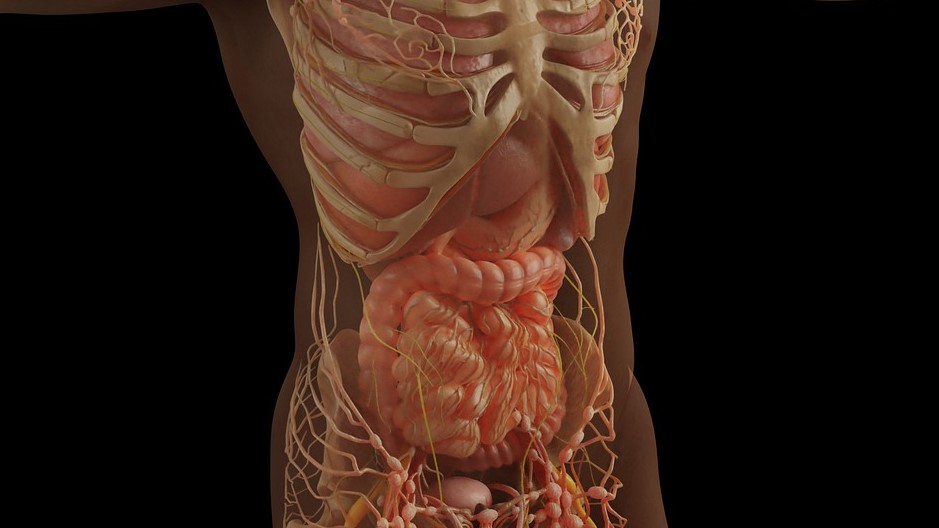

Irritable bowel syndrome affects an estimated 4-11% of all people, and a majority of patients prefer dietary interventions to medication. The low FODMAP diet leads to symptom improvement in more than half of patients, but is restrictive and hard to follow.

Previous investigations from Michigan Medicine researchers into more accessible alternative diets led to a proposed “FODMAP simple,” which attempted to only restrict the food groups in the FODMAP acronym that are most likely to cause symptoms.

“Restrictive diets, such as low FODMAP, can be difficult for patients to adopt,” said Prashant Singh, MBBS, Michigan Medicine gastroenterologist and lead author on the paper.

“In addition to the issue of being costly and time-consuming, there are concerns about nutrient deficiencies and disordered eating when trying a low FODMAP diet. The Mediterranean diet interested us as an alternative that is not an elimination diet and overcomes several of these limitations related to a low FODMAP diet.”

The Mediterranean diet is already popular among physicians for its benefits to cardiovascular, cognitive, and general health. Previous research on the effect of the Mediterranean diet on IBS, however, had yielded conflicting results.

In this pilot study, two groups of patients, diagnosed with either IBS-D (diarrhoea) or IBS-M (mixed symptoms of constipation or diarrhoea), were provided with either a Mediterranean diet or the restriction phase of a low FODMAP diet for four weeks.

The primary endpoint was an FDA-standard 30% reduction in abdominal pain intensity after four weeks.

This study was the first randomised controlled trial to compare the Mediterranean diet to another potential diet. While the Mediterranean diet did provide symptom relief, the low FODMAP group experienced a greater improvement measured by both abdominal pain intensity and IBS symptom severity score.

Researchers found the results of this pilot study, which 20 patients completed, sufficiently encouraging to warrant future, larger controlled trials to investigate the potential of the Mediterranean diet as an effective intervention for patients with IBS.

“This study adds to a growing body of evidence which suggests that a Mediterranean diet might be a useful addition to the menu of evidence-based dietary interventions for patients with IBS,” said William Chey, MD, chief of Gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, president-elect of the American College of Gastroenterology, and senior author on the paper.

The researchers believe studies comparing long-term efficacy of the Mediterranean diet with long-term outcomes following the reintroduction and personalisation phases of low FODMAP are needed.