Genetic Analysis Reveals Secrets of Vlad Dracula the Impaler

Mediaeval tyrant and inspiration for vampires, protein analysis reveals health secrets about Vlad the Impaler

New research analysing ancient protein residues left in letters written by the sadistic 15th century tyrant – and vampire inspiration – Vlad Dracula the Impaler suggests that he suffered from a number of health conditions. One of these conditions seemingly confirms one of the more outlandish tales about him – that he cried tears of blood.

Vlad the Impaler got his nickname because he impaled thousands of people on stakes: enemies (mainly the Ottoman Empire), criminals and anyone suspected of conspiring against his rule. He was eventually defeated in 1460, but the newly invented printing press spread the tale of his gruesome deeds all over Europe. Tales surrounding him may have inspired the iconic character of Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula in 1897. Nevertheless, more modern vampire stories such as Netflix’s ‘Castlevania’ make use of Vlad as inspiration.

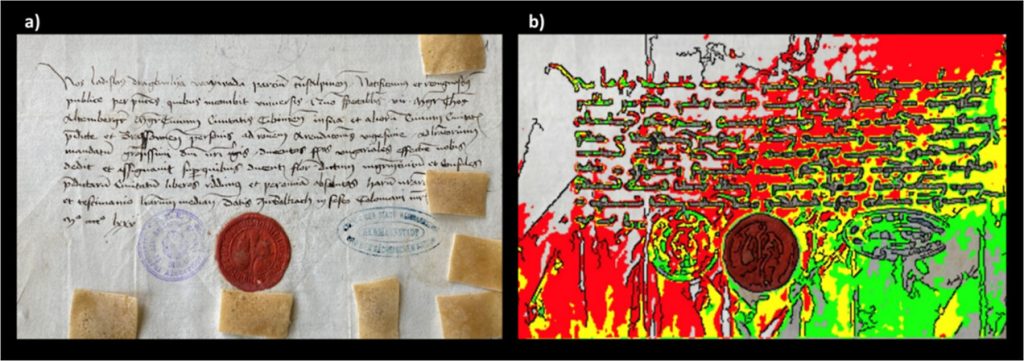

This terrifying reputation made him an interesting topic for a bit of genetic archaeology in a paper published in Analytical Chemistry. Using sophisticated proteomic techniques, scientists analysed three letters written in 1457 and 1475 by the voivode of Wallachia, Vlad III, also known as Vlad the Impaler, or Vlad Dracula. This allowed them to tease out information about the man who wrote the letters as well as general information about the environmental conditions of 15th century Wallachia, a place of regional trade and conflict as well as disease transmission.

While centuries-old paper is unlikely to hold entire DNA strands, scientists were still able to piece together genetic information about the writer. The technique depends on the notion that a person’s writing hand will tend to rest on the paper being written upon, rubbing off a surprising amount of organic molecules in the process. They applied ethylene vinyl acetate to the papers, and with mass spectrometry, they discovered over 500 peptides – short chains of amino acids – with about 100 being of human origin, which they looked up in database searches.

The researchers noted that while many mediaeval people may have handled these papers, it is also presumable that the most prominent ancient proteins can be attributed to the one who wrote and signed them – Prince Vlad the Impaler.

First, they discovered proteins pointing to ciliopathy, which affects the cellular cilia or the cilia anchoring structures, the basal bodies or ciliary function. This can manifest in a wide range of disorders, ranging from cerebral malformation to liver disease and intellectual disability.

They also uncovered signs of an undetermined inflammatory disease which likely involved his skin and respiratory tract.

Proteomics data also suggests that, according to some stories, he might also have suffered from a pathological condition called haemolacria – he could shed tears admixed with blood. This appears to confirm what some stories said about Vlad – that he sometimes cried tears of blood. While it is a known medical condition, it would have no doubt been terrifying for superstitious mediaeval people to behold when seen in someone with a reputation like Vlad the Impaler’s.

Non-human peptides also proved to be a window into the conditions of the time, hinting at common foods, pests and diseases. Database searches of the identified, as potential endogenous original components, 3 proteins from bacteria, 24 from viruses, 4 from fungi, 17 from insects (suggesting fruit flies), and 5 from plants (including rice, wheat and thale cress). Of the bacteria, they noted that some peptides related to Enterobacterales are specific to Yersinia pestis, the pathogenic bacterium causing plague, whereas another group is specific to E. coli.