New Study Supports Caution on Corticosteroids Use in Lupus Heart Condition

A new study of more than 2900 patients provides evidence that it’s likely best to use as little corticosteroid medicine as possible when treating people who have lupus pericarditis, a common heart complication of the autoimmune disease Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE).

This study, funded by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and led by Johns Hopkins Medicine cardiologists and rheumatologists who led the study say their analysis of data affirms that using steroids to curb heart inflammation and other painful symptoms for lupus patients is also a risk factor for recurring pericarditis,.

Results of this study were published in JAMA Network Open.

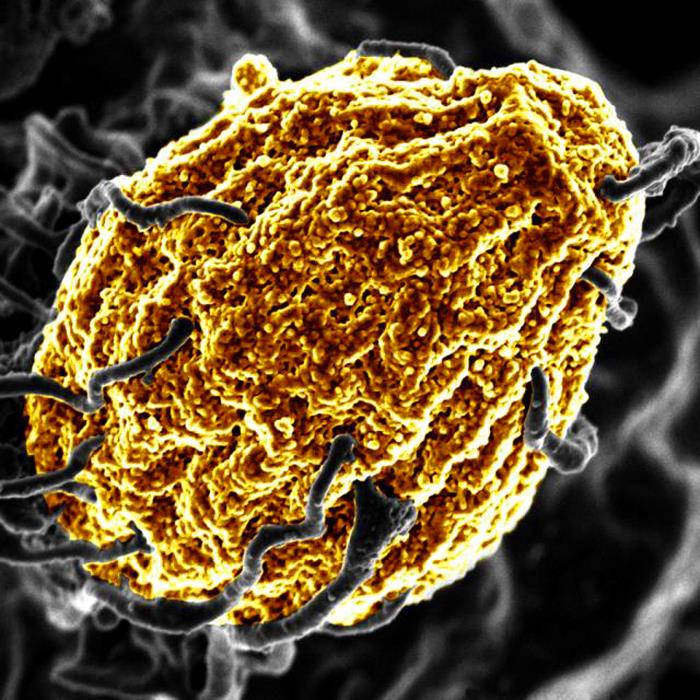

The American Heart Association defines pericarditis as inflammation of the pericardium, the twin-layered sac-like structure surrounds the heart to hold it in place and help protect it. Pericarditis typically presents as chest pain that can be exacerbated by lying flat and improved by leaning forward. This pain can last anywhere from a few days to several months. Treatment options for pericarditis include use of colchicine, an anti-inflammatory medication that prevents the recurrence of pericarditis, and corticosteroids.

Pericarditis occurs in 15% to 30% of patients with SLE, a chronic autoimmune disease that causes the body’s immune system to attack its own tissues. “It is well known that, in the general population, one fifth of patients who experience pericarditis end up experiencing one or more recurrences. Surprisingly, even though pericarditis is the most common cardiac complication of Lupus, we could not find any information on recurrent of pericarditis in this patient population,” says Dr Luigi Adamo, MD, PhD, director of Cardiac Immunology at Johns Hopkins University and co-senior author of this study.

Researchers set out to address this gap in knowledge and examine the risk factors contributing to the recurrence.

For the new analysis, researchers used data gathered among the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, a large ongoing study group that includes information on 2,931 patients diagnosed with SLE between 1988 to 2023 and the investigators focused on data from 590 patients also diagnosed with pericarditis. Pericarditis in the data set was identified using the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment – SLE Disease Activity Index (SELENA-SLEDAI), a standard tool in the assessment of SLE clinical activity.

Study results showed that 20% of patients with Lupus who experienced pericarditis had a recurrence. Recurrent pericarditis was most prevalent among patients within the first year of pericarditis onset, with recurrence decreasing in the following years. Younger patients and those with uncontrolled disease were at greater risk of recurrence. It was noted that oral prednisone therapy, a tool frequently used to treat pericarditis in patients with autoimmune diseases, was associated with a higher chance of pericarditis recurrence in patients with SLE.

“The cardiology literature has shown that use of corticosteroids increases the risk of recurrent pericarditis in the general population. Nevertheless, steroids are very frequently used by rheumatologists to treat lupus pericarditis. Therefore, the findings from this study underscore the importance of minimising oral corticosteroid use in patients with lupus and indicate the need for alternative strategies.” said Andrea Fava, MD, a rheumatologist who specialises in care of patients with lupus and co-senior author of the study.

Source: Johns Hopkins Medicine