Low-carb Diet’s Colorectal Cancer Risk is Mediated by the Gut Microbiome

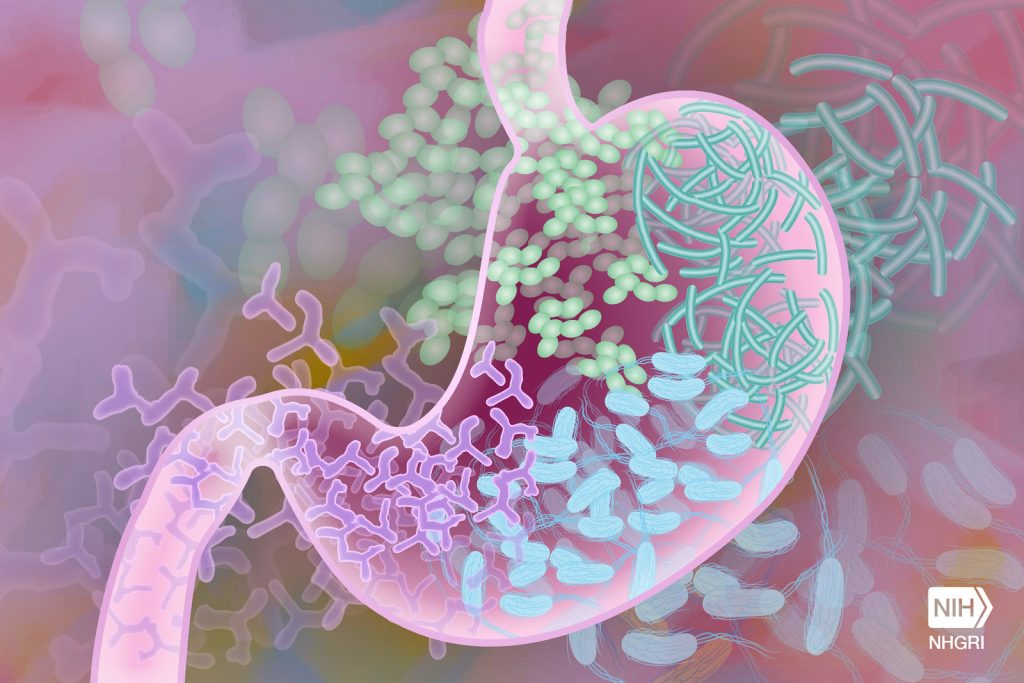

Researchers from the University of Toronto have shown how a low-carbohydrate diet can worsen the DNA-damaging effects of some gut microbes to cause colorectal cancer.

The study, published in the journal Nature Microbiology, compared the effects of three different diets: normal, low-carb, or Western-style with high fat and high sugar, each in combination with specific gut bacteria on colorectal cancer development in mice.

They found that a unique strain of E. coli bacteria, when paired with a diet low in carbs and soluble fibre, drives the growth of polyps in the colon, which can be a precursor to cancer.

“Colorectal cancer has always been thought of as being caused by a number of different factors including diet, gut microbiome, environment and genetics,” says senior author Alberto Martin, a professor of immunology at U of T’.

“Our question was, does diet influence the ability of specific bacteria to cause cancer?”

To answer this question, the researchers, led by postdoctoral fellow Bhupesh Thakur, examined mice that were colonized with one of three bacterial species that had been previously linked to colorectal cancer and fed either a normal, low-carb or Western-style diet.

Only one combination, a low-carb diet paired with a strain of E. coli that produces the DNA-damaging compound colibactin, led to the development of colorectal cancer.

The researchers found that a diet deficient in fibre increased inflammation in the gut and altered the community of microbes that typically reside there, creating an environment that allowed the colibactin-producing E. coli to thrive.

They also showed that the mice fed a low-carb diet had a thinner layer of mucus separating the gut microbes from the colon epithelial cells. The mucus layer acts as a protective shield between the bacteria in the gut and the cells underneath. With a weakened barrier, more colibactin could reach the colon cells to cause genetic damage and drive tumour growth. These effects were especially strong in mice with genetic mutations in the mismatch repair pathway that hindered their ability to fix damaged DNA.

While both Thakur and Martin emphasize the need to confirm these findings in humans, they are also excited about the numerous ways in which their research can be applied to prevent cancer.

Defects in DNA mismatch repair are frequently found in colorectal cancer, which is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer in Canada. An estimated 15 per cent of these tumours having mutations in mismatch repair genes. Mutations in these genes also underlie Lynch syndrome, a genetic condition that significantly increases a person’s risk of developing certain cancers, including colorectal cancer.

“Can we identify which Lynch syndrome patients harbour these colibactin-producing microbes?” asks Martin. He notes that for these individuals, their findings suggest that avoiding a low-carb diet or taking a specific antibiotic treatment to get rid of the colibactin-producing bacteria could help reduce their risk of colorectal cancer.

Martin points out that a strain of E. coli called Nissle, which is commonly found in probiotics, also produces colibactin. Ongoing work in his lab is exploring whether long-term use of this probiotic is safe for people with Lynch syndrome or those who are on a low-carb diet.

Thakur is keen to follow up on an interesting result from their study showing that the addition of soluble fibre to the low-carb diet led to lower levels of the cancer-causing E. coli, less DNA damage and fewer tumours.

“We supplemented fibre and saw that it reduced the effects of the low-carb diet,” he says. “Now we are trying to find out which fibre sources are more beneficial, and which are less beneficial.”

To do this, Thakur and Martin are teaming up with Heather Armstrong, a researcher at the University of Alberta, to test whether supplementation with a soluble fibre called inulin can reduce colibactin-producing E. coli and improve gut health in high-risk individuals, like people with inflammatory bowel disease.

“Our study highlights the potential dangers associated with long-term use of a low-carb, low-fibre diet, which is a common weight-reducing diet,” says Martin.

“More work is needed but we hope that it at least raises awareness.”

Source: University of Toronto