Sitting Less may Prevent Back Pain – Even Without Exercise

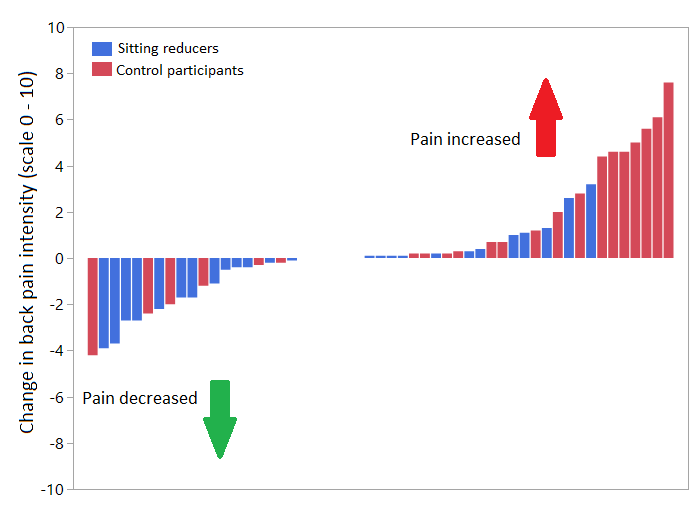

A new study from the University of Turku showed that reducing daily sitting prevented back pain from worsening over six months. The results, published in BMJ Open, strengthen the current understanding of the link between activity and back pain as well as the mechanisms related to back pain.

Intuitively, it is easy to think that reducing sitting would help with back pain, but previous research data is surprisingly scarce. The study from the Turku PET Centre and UKK Institute in Finland investigated whether reducing daily sitting could prevent or relieve back pain among overweight or obese adults who spend the majority of their days sitting. The participants were able to reduce their sitting by 40 min/day, on average, during the six-month study.

“Our participants were quite normal middle-aged adults, who sat a great deal, exercised little, and had gained some extra weight. These factors not only increase the risk for cardiovascular disease but also for back pain,” says Doctoral Researcher and Physiotherapist Jooa Norha from the University of Turku in Finland.

Previous results from the same and other research groups have suggested that sitting may be detrimental for back health but the data has been preliminary.

Robust methods for studying the mechanisms behind back pain

The researchers also examined potential mechanisms behind the prevention of back pain.

”However, we did not observe that the changes in back pain were related to changes in the fattiness or glucose metabolism of the back muscles,” Norha says.

Individuals with back pain have excessive fat deposits within the back muscles, and impaired glucose metabolism, or insulin sensitivity, can predispose to pain. Nevertheless, back pain can be prevented or relieved even if no improvements in the muscle composition or metabolism take place. The researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET imaging that is based on a radioactive tracer to measure the back muscles.

“If you have a tendency for back pain or excessive sitting and are concerned for your back health, you can try to figure out ways for reducing sitting at work or during leisure time. However, it is important to note that physical activity, such as walking or more brisk exercise, is better than simply standing up,” Norha points out.

The researchers wish to remind that switching between postures is more important than only looking for the perfect posture.

Source: University of Turku