TB Alters Liver Metabolism and could Promote Diabetes, Study Shows

Scientists from the University of Leicester have discovered that tuberculosis disrupts glucose metabolism in the body. The findings, which have now been published in PLoSPathogens complement the understanding that diabetes worsens the symptoms of tuberculosis. Importantly, they now say, undiagnosed tuberculosis could be pushing vulnerable patients towards metabolic disease such as diabetes.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the most devastating infectious diseases worldwide, killing over 4,000 people every day. Prevention through the development of improved vaccines remains a priority for the World Health Organisation. Currently only one vaccine exists for TB and this is predominantly given to infants and young children to help protect them from severe forms of infection.

Scientists at the University are researching tuberculosis in the hope of creating improved vaccines and are specifically looking at ways in which undiagnosed and subclinical infection can impact health. This new discovery, they say, could pave the way to define the molecular pathways by which the immune response changes liver metabolism, thereby allowing for the creation of targeted interventions.

Professor Andrea Cooper from the University’s Leicester Tuberculosis Research Group (LTBRG), is among the authors on the paper.

She said: “Our paper changes the focus from diabetes making TB worse to the possibility that late diagnosis of TB can contribute to disruption of glucose metabolism, insulin resistance and therefore can promote progress towards diabetes in those that are susceptible.

“As diabetes compromises drug treatment, our paper also supports the idea that metabolic screening should be involved in any drug or vaccine trials.”

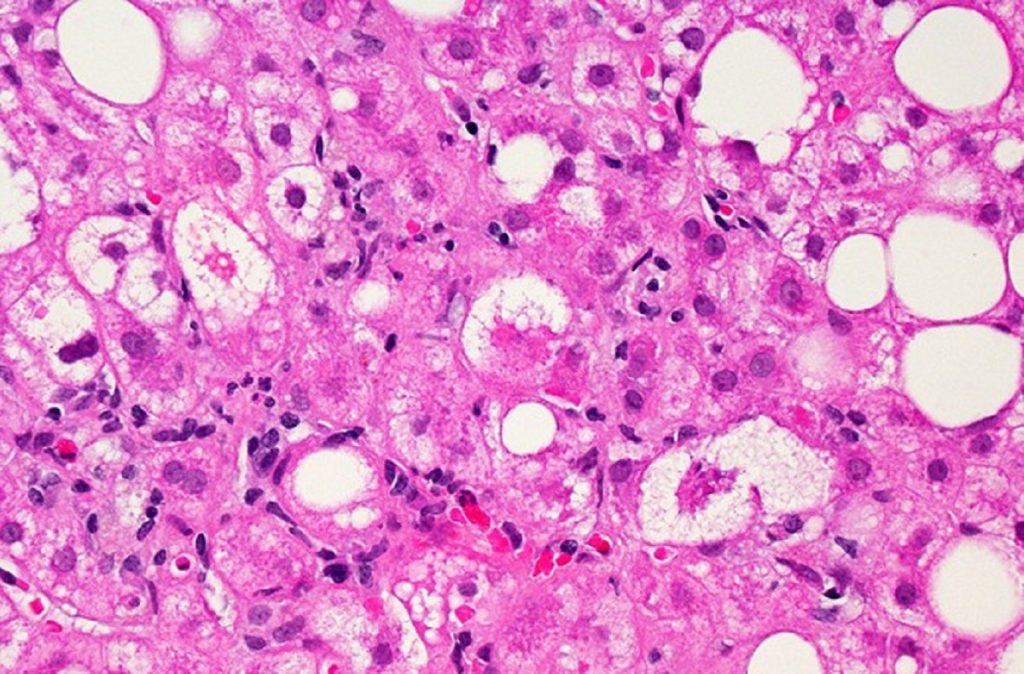

The study first used laboratory models of pulmonary TB to examine the changes happening within the liver during the early stages of infection. It found that an immune response was triggered within the liver cells and glucose metabolism was altered.

First author Dr Mrinal Das then reanalysed published metabolic data from humans, where he found that liver glucose metabolism was also disrupted when people progressed to TB from latent infection.

Professor Cooper added: “Our future aim is to define the molecular pathways by which the immune response is changing liver metabolism, allowing us to potentially create targeted interventions.

“We will also be investigating how latent TB (which is infection with the bacterial agent of TB without significant symptoms) might be impacting metabolic health in humans.”

Source: University of Leicester