Higher Doses of Lithium might Relieve Long COVID, Research Suggests

A small University at Buffalo clinical trial has found that at low doses, lithium aspartate is ineffective in treating the fatigue and brain fog that is often a persistent feature of long COVID; however, a supplemental dose-finding study found some evidence that higher doses may be effective.

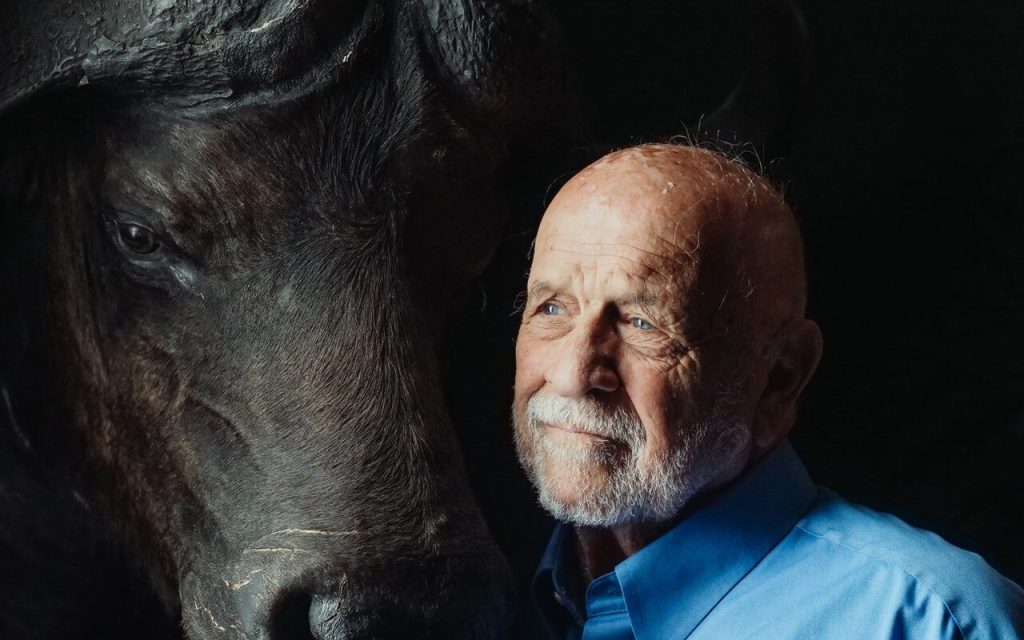

Published in JAMA Network Open, the study was led by Thomas J. Guttuso, Jr., MD, professor of neurology in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB and a physician with UBMD Neurology.

“It’s a negative study with a positive twist,” Guttuso concludes.

Because long COVID is believed to stem from chronic inflammation and lithium has known anti-inflammatory actions, Guttuso had recommended that a patient of his try low-dose lithium for persistent long COVID symptoms. He was surprised when this patient reported a near full resolution of fatigue and brain fog within a few days of initiating lithium aspartate at 5mg a day.

Relief from symptoms

Based on this single case, Guttuso became interested in lithium aspartate as a potential treatment for long COVID and recommended it to other such patients.

According to Guttuso, 9 of 10 long COVID patients he treated with lithium aspartate 5-15mg a day saw very good benefit in terms of improvements to their fatigue and brain fog symptoms.

“Based on those nine patients, I had high hopes that we would see an effect from this randomized controlled trial,” says Guttuso. “But that’s the nature of research. Sometimes you are unpleasantly surprised.”

The randomised controlled trial showed no benefit from 10-15mg a day of lithium aspartate compared to patients receiving a placebo.

After one patient from the study subsequently increased the lithium aspartate dosage to 40mg a day and experienced a marked reduction in fatigue and brain fog symptoms, Guttuso decided to then conduct a dose-finding study designed to explore if a higher dose of lithium aspartate may be effective.

The three participants who completed the dose-finding study reported greater declines in fatigue and brain fog with the higher dose of 40-45mg per day. This was especially true in the two patients with blood lithium concentrations of 0.18 and 0.49mmol/L compared to one patient with a level of 0.10mmol/L who saw partial improvements.

“This is a very small number of patients, so these findings can only be seen as preliminary,” says Guttuso. “Perhaps achieving higher blood levels of lithium may provide improvements to fatigue and brain fog in long COVID.”

Dosage may be too low

He notes that it is possible the randomized controlled trial was ineffective because the dose of lithium aspartate that was used was too low.

“The take-home message is that very low dose lithium aspartate, 10-15 milligrams a day, is ineffective in treating the fatigue and brain fog of long COVID,” says Guttuso. “Perhaps we need to do another randomised controlled trial that uses higher lithium aspartate dosages that achieve blood lithium levels of 0.18-0.50mmol/L to determine if they could be effective.”

An estimated 17 million people have long COVID in the US, and worldwide the number is estimated at 65 million.

“There currently are no evidence-based therapies for long COVID,” says Guttuso. He hopes that the National Institutes of Health will view lithium as worth studying through a trial with higher dosages; the NIH is allocating an additional $500 million to study long COVID therapies that appear to be promising.

Guttuso adds that if a subsequent randomised controlled trial finds that higher dosages of lithium aspartate are effective, long COVID patients would still need to discuss taking it with their health care providers; in addition, he says, if they do begin taking it at higher dosages, blood lithium levels should be monitored.

Source: University at Buffalo