Lassa Virus Endemic Area may Grow in Coming Decades

Analysing decades of environmental data associated with Lassa virus outbreaks, researchers projected that areas hospitable to Lassa virus spread may extend from West Africa into Central and East Africa in the next several decades. With this expansion and expected African population growth, the human population living in the areas where the virus should theoretically be able to circulate may rise by more than 600 million.

“Our analysis shows how climate, land use, and population changes in the next 50 years could dramatically increase the risk of Lassa fever in Africa,” says first author Raphaëlle Klitting, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at Scripps Research during the study, which is published in Nature Communications.

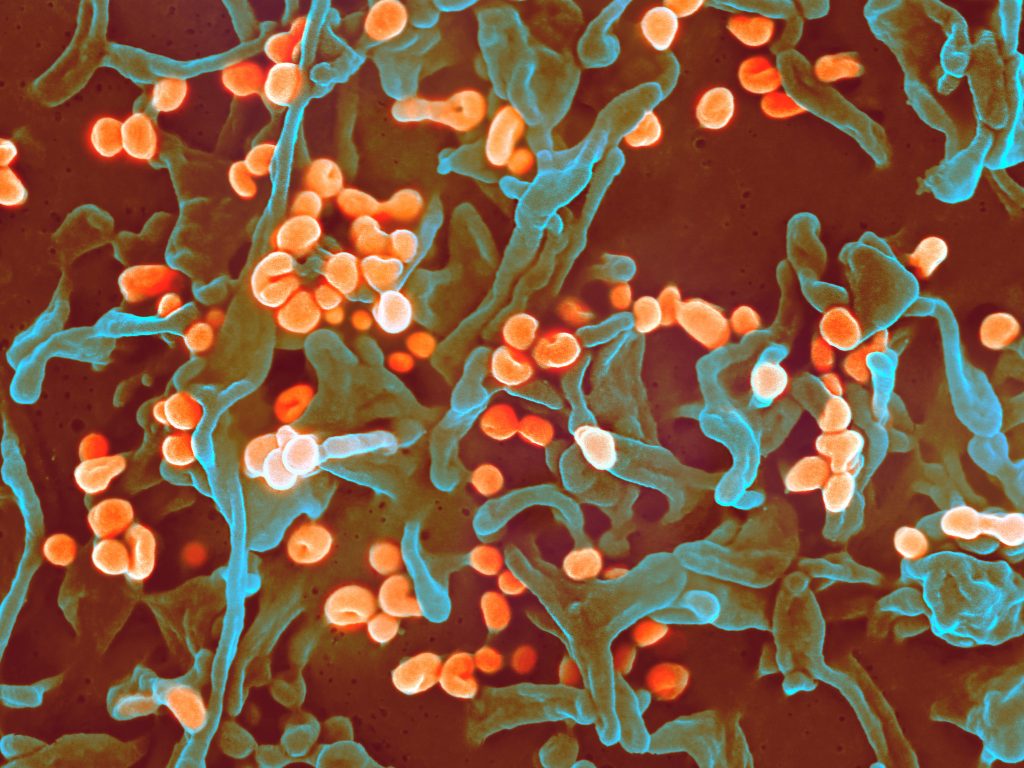

Lassa virus is a zoonotic pathogen found in the Natal multimammate rat (Mastomys natalensis), most likely transmitted to humans via its droppings. While an estimated 80% of infections are mild or asymptomatic, the remaining cases are more severe, with signs and symptoms that can include haemorrhaging from the mouth and gut, hypotension, and potentially permanent hearing loss. Mortality rate in hospitalised patients can be up to 80%.

An estimated several hundred thousand infections occur each year, chiefly in Nigeria and several other West African countries. So far there is no approved vaccine or highly effective drug treatment.

Although the primary animal reservoir for Lassa virus is known, the virus spreads in only a subset of the areas where the animal is found. Thus, it is possible that environmental factors also help determine whether and where significant viral transmission can occur. In the study, the researchers developed an ‘ecological niche’ model of Lassa virus transmission, using environmental data at sites of known spread.

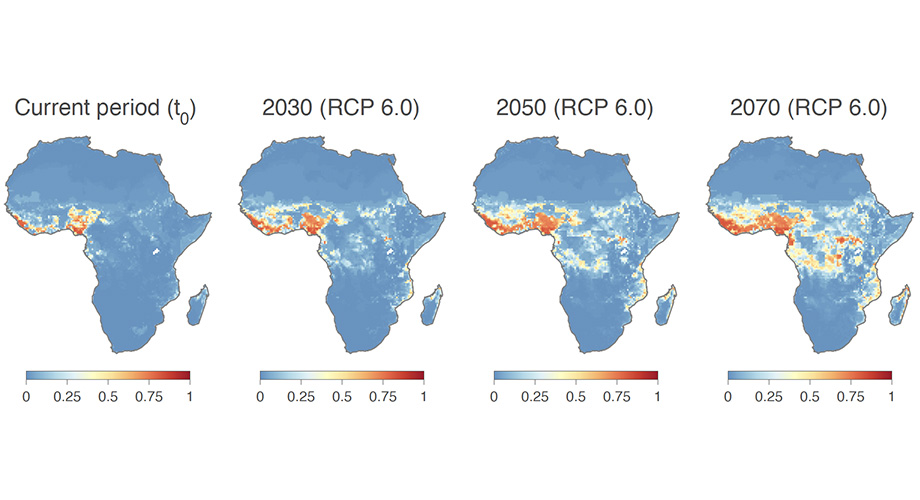

Combining the model with projections of climate and land-use changes in Africa in the next several decades, as well as the known range of the Natal multimammate rat, the researchers estimated the areas of Africa that could support Lassa virus transmission currently, and in the years 2030, 2050, and 2070. The projected current areas corresponded well to known endemic areas in West Africa, but the estimates for future decades suggested a vast expansion within and beyond West Africa.

“We found that several regions will likely become ecologically suitable for virus spread in Central Africa, including in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and even in East Africa, in Uganda,” Klitting said.

Currently Africa’s population is undergoing rapid growth; the researchers therefore considered projections of this population growth for the areas of current and potential future Lassa virus circulation. They found that the number of people potentially exposed to the virus could increase from about 92 million today to 453 million by 2050, and 700 million by 2070 – an increase of over 600%.

More hopefully, the researchers examined the dynamics of the spread of Lassa virus using data on sequenced viral genomes sampled at various locations in West Africa and found that virus dispersal appeared to be slow. They concluded that, unless transmission dynamics change drastically in the new location where the virus circulates, the virus’s spread into new ecologically suitable areas in the coming decades may also be slow.

The authors say that the findings should inform African public health policies, for example, by encouraging officials to add Lassa virus to lists of viruses under epidemiologic surveillance in parts of Central and East Africa.

“With the ongoing climate change and increasing impact of human activities on the environment, further comprehensive studies of the ecology and spread of zoonotic and vector-borne diseases are needed to anticipate possible future changes in their distribution as well as their impact on public health,” said senior author Simon Dellicour, PhD, of the University of Brussels.

Source: Scripps Research Institute