New Intervention Boosts Diagnosis and Care of Brain Infection

University of Liverpool researchers have worked with global partners to identify and successfully implement an intervention package that has significantly improved the diagnosis and management of brain infections in hospitals across Brazil, India, and Malawi.

The study, published in The Lancet, was coordinated by researchers at the University of Liverpool in collaboration with international partners and implemented across 13 hospitals.

The intervention included:

• A clinical algorithm which offered a flowchart of guidance for clinicians on how to manage the first crucial hours and days of suspected brain infections, including which tests (blood tests, lumbar puncture, brain scans) and treatments to administer.

• A lumbar puncture pack, providing clinicians with sample containers, equipment, and guidance to ensure proper cerebrospinal fluid collection and testing, addressing challenges like knowing how much fluid to take and which tests to request.

• A panel of laboratory tests to enable correct and timely testing for a wide range of pathogens, addressing gaps in availability and sequencing of tests, with the main goal of identifying the cause of infection.

• Training for clinicians and lab staff to enhance their knowledge and skills in diagnosing and managing brain infections, including proper use of the new intervention tools.

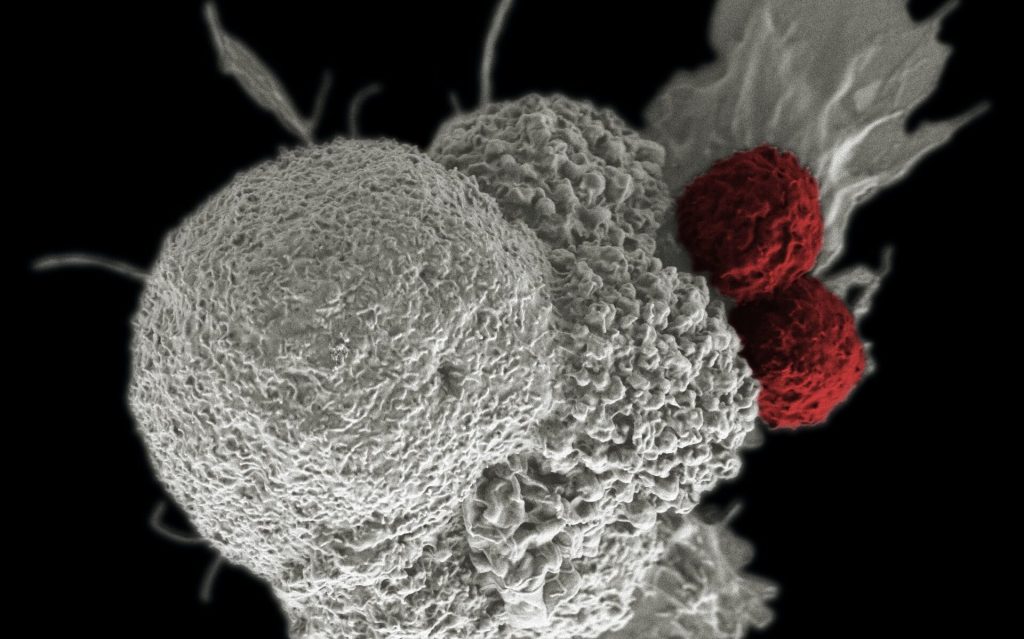

These measures led to significant improvements in diagnosing patients with suspected acute brain infections, such as encephalitis and meningitis. Both conditions cause significant mortality and morbidity, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where diagnosis and management are hindered by delayed lumbar punctures, limited testing, and resource constraints. Improved diagnosis and optimal management are a focus for the World Health Organization (WHO) in tackling meningitis and reducing the burden of encephalitis.

As a result of the intervention package, the proportion of patients receiving a syndromic diagnosis (confirming they had a brain infection) increased from 77% to 86%, while the microbiological diagnosis rate (identifying the exact pathogen) rose from 22% to 30%. In addition to improving diagnosis, the intervention enhanced the performance of lumbar punctures, optimised initial treatment, and improved patients’ functional recovery after illness.

Lead author Dr Bhagteshwar Singh, Clinical Research Fellow, Clinical Infection, Microbiology & Immunology said: “Following patients and their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples through the hospital system, we tailored our intervention to address key gaps in care. The results speak for themselves: better diagnosis, better management, and ultimately, better outcomes for patients. Unlike most studies, we embedded improvements into routine care, so the impact continues well beyond the study.”

Corresponding author Professor Tom Solomon, Chair of Neurological Science at the University of Liverpool and Director of The Pandemic Institute, added: “We increased microbiological diagnoses by one-third across very diverse countries, which has profound implications for treatment and public health globally. As we scale this up in more hospitals and feed it into national and international policy, including WHO’s work on defeating meningitis and controlling encephalitis, the potential impact is enormous.”

The intervention was co-designed by clinicians, lab specialists, hospital administrators, researchers, and policymakers in each country, ensuring it was feasible and sustainable. Professor Priscilla Rupali, lead researcher from Christian Medical College, Vellore, India, also commented: “The co-design process ensured that the intervention would work within local healthcare settings and could be sustained beyond the study. We are already incorporating the findings into India’s national Brain Infection Guidelines, ensuring long-term benefits for patient care.”

The intervention package is freely available as a toolkit for adaptation in different settings: https://braininfectionsglobal.tghn.org/resources/brain-infections-global-tools/.

Source: University of Liverpool