Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine Tech Tapped to Treat Cancer

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine’s success against SARS-CoV-2 has prompted scientists to develop a vaccine for cancer, using Oxford’s viral vector vaccine technology.

When tested in mouse tumour models, the two-dose therapeutic cancer vaccine increased the numbers of anti-tumour T cells infiltrating the tumours and improved the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Compared to immunotherapy alone, combination with the vaccine resulted in a greater reduction in tumour size and improved survival.

The study, which was done by Professor Benoit Van den Eynde’s group at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, University of Oxford in collaboration with co-authors Professor Adrian Hill and Dr Irina Redchenko at the University’s Jenner Institute, has been published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer.

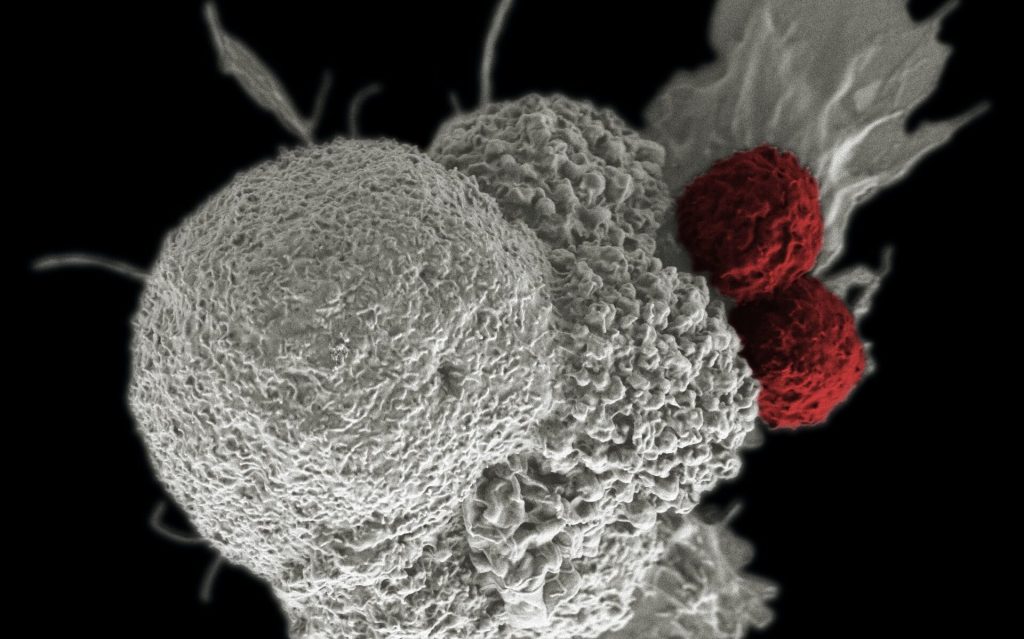

Cancer immunotherapy has improved outcomes for some cancer patients. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy works by unleashing anti-tumour T cells to allow them to kill cancer cells. However, in the majority of cancer patients, anti-PD-1 therapy is still ineffective .

One reason for the poor efficacy of anti-PD-1 cancer therapy is that some patients have low levels of anti-tumour T cells. Oxford’s vaccine technology generates strong CD8+ T cell responses, which are necessary for strong anti-tumour effects.

The team developed a two-dose therapeutic cancer vaccine with different prime and boost viral vectors, one of which is the same as the vector in the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID vaccine. In order to create a vaccine treatment that specifically targets cancer cells, the vaccine was designed to target two MAGE-type proteins found on the surface of many types of cancer cells.

Preclinical experiments in mouse tumour models demonstrated that the cancer vaccine increased the levels of tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and enhanced the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. The combined vaccine and anti-PD-1 treatment resulted in a greater reduction in tumour size and improved the survival of the mice compared to anti-PD-1 therapy alone.

Benoit Van den Eynde, Professor of Tumour Immunology at the University of Oxford, said: “We knew from our previous research that MAGE-type proteins act like red flags on the surface of cancer cells to attract immune cells that destroy tumours.

“MAGE proteins have an advantage over other cancer antigens as vaccine targets since they are present on a wide range of tumour types. This broadens the potential benefit of this approach to people with many different types of cancer.

“Importantly for target specificity, MAGE-type antigens are not present on the surface of normal tissues, which reduces the risk of side-effects caused by the immune system attacking healthy cells.”

Human trials in 80 patients with non-small cell lung cancer will be launched later this year.

Adrian Hill, Lakshmi Mittal and Family Professorship of Vaccinology and Director of the Jenner Institute, University of Oxford, said: “This new vaccine platform has the potential to revolutionise cancer treatment. The forthcoming trial in non-small cell lung cancer follows a Phase 2a trial of a similar cancer vaccine in prostate cancer undertaken by the University of Oxford that is showing promising results.

“Our cancer vaccines elicit strong CD8+ T cell responses that infiltrate tumours and show great potential in enhancing the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy and improving outcomes for patients with cancer.”

Source: Oxford University