Case Reveals a Rare Side Effect of Cancer Immunotherapy

The genetically modified CAR-T cells meant to treat the cancer themselves turned cancerous

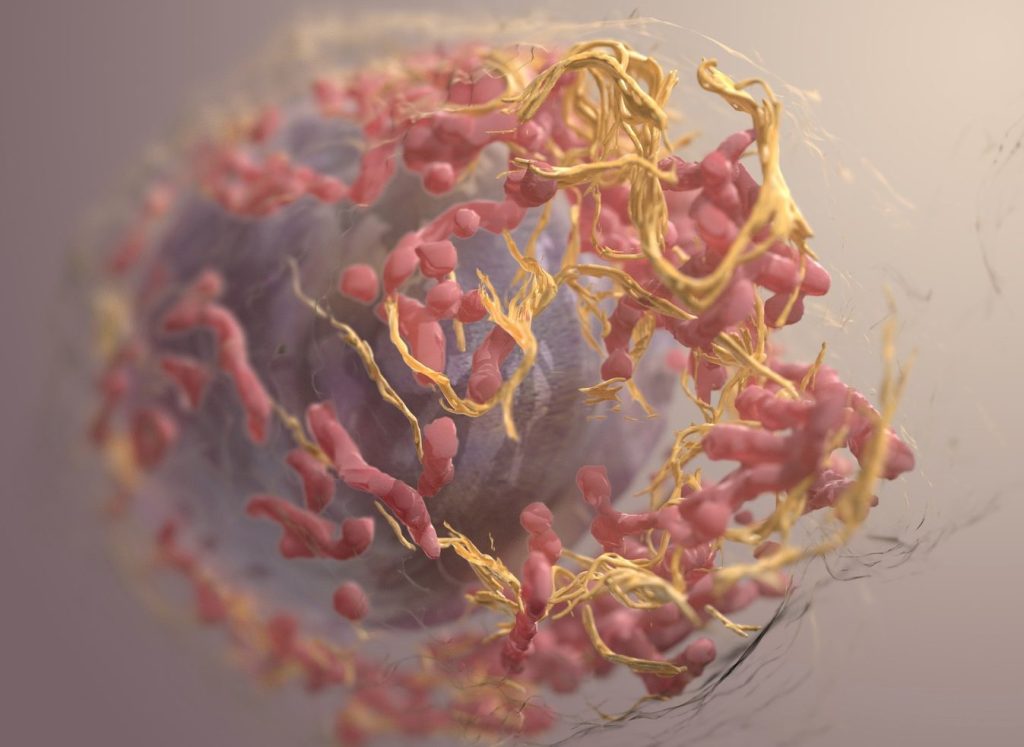

Some forms of blood cancer, such as multiple myeloma and lymphoma, are malignant diseases that originate from immune cells, specifically lymphocytes. In recent years, CAR-T cell therapies have become an essential part of the treatment of patients whose lymphoma or multiple myeloma has relapsed. This involves genetically modifying the patient’s own T lymphocytes (T cells) in order to specifically recognise and eliminate the cancer cells using a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

One special case is the subject of an article published in Nature Medicine. A 63-year-old patient with multiple myeloma developed T cell lymphoma in the blood, skin and intestine nine months after undergoing CAR-T cell therapy at the University Hospital of Cologne. The tumour developed from the genetically modified T cells that were used in the treatment.

The initiators of this collaborative project, Professor Marco Herling, managing senior physician at the University of Leipzig Medical Center and Dr Till Braun, research group leader at the University Hospital of Cologne, have world-renowned expertise in understanding the rare but difficult-to-treat T cell lymphomas. “This is one of the first documented cases of such lymphoma following CAR-T cell therapy. The findings of this study will help us to better understand the risks associated with the therapy and possibly prevent them in the future,” says Professor Maximilian Merz, who led the current study as corresponding author together with Professor Marco Herling from the University of Leipzig Medical Center.

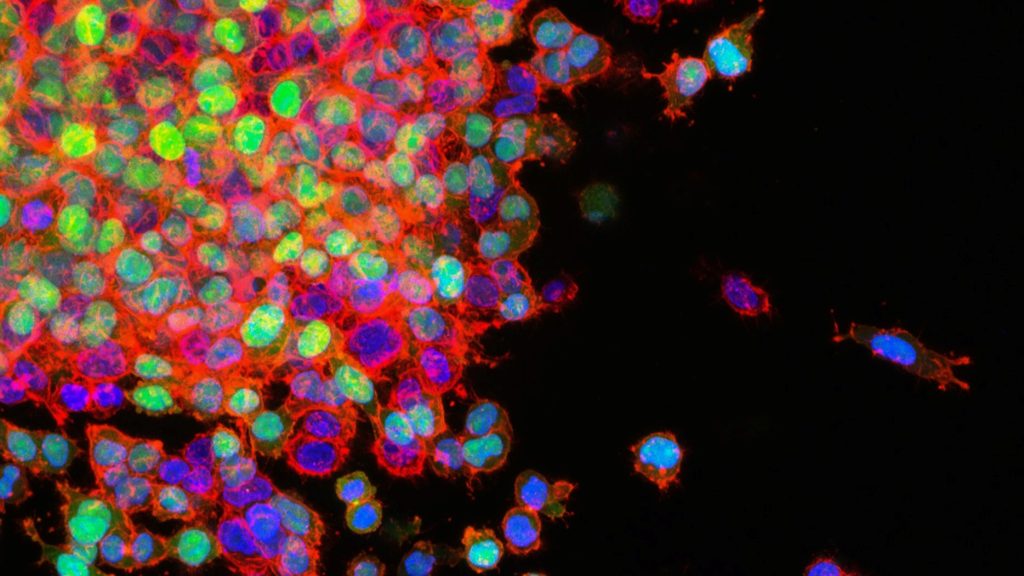

The researchers discovered that it was not just current genetic alterations of the T cells that caused the tumour. Pre-existing genetic changes in the patient’s haematopoietic cells also played a role. The researchers used cutting-edge technologies to study the tumour’s development in detail. Various methods of next-generation sequencing – an advanced, high-throughput technology for analysing DNA and RNA sequences – were used to study the phenomenon. Whole-genome sequencing was used to identify genetic alterations, while single-cell RNA sequencing analysed the transcriptome of the CAR-T cells to investigate genes and signalling pathways.

These methods had previously been developed in close collaboration between the research groups of Professor Merz at the University of Leipzig Medical Center and Dr Kristin Reiche at the Fraunhofer IZI. The close collaboration between clinicians and basic scientists in the field of CAR-T cell therapy allowed for the case to be analysed in a very short time. The University of Leipzig Medical Center is one of the leading centres in Europe for the treatment of multiple myeloma with CAR-T cells and of T cell lymphoma. “This case provides valuable insights into the emergence and development of CAR-bearing T cell lymphoma following innovative immunotherapies and highlights the importance of genetic predispositions for potential side effects,” says Professor Merz, Senior Physician at the Department for Hematology, Cell Therapy and Hemostaseology at the University of Leipzig Medical Center.

The researchers are planning further scientific studies to better understand similar cases and identify risk factors. The aim is to be able to predict and prevent such side effects after CAR-T cell therapies, which are currently being used more and more widely, in the future. The high relevance of the topic of secondary tumours after CAR-T cell therapy has now been highlighted in a second scientific paper. The same research team submitted a manuscript to the high-impact journal Leukemia that systematically summarises this patient case and the nine other recently published cases of T cell lymphoma from CAR-T cells worldwide. Normally, it takes several weeks to months for peer reviewers to accept a scientific paper for publication. In this case, the manuscript was accepted for publication within a day. “It is important to create a real, data-based awareness of the rarity of this complication, at far less than one per cent, and the mechanisms by which it occurs,” says Professor Herling.

Source: Universität Leipzig