Too Few Children with HIV are Virally Suppressed

Globally, less than two thirds of children and adolescents living with HIV who are receiving treatment are virally suppressed, according to new research published in The Lancet HIV.

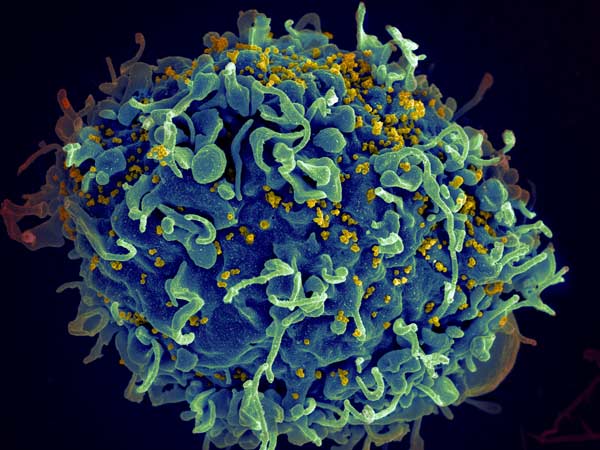

Viral suppression [PDF] for HIV means that treatments are protecting health and preventing the transmission of HIV to others. UNAIDS has set a target of achieving 95% viral suppression among all people living with HIV on treatment by 2030.

“We estimate viral suppression one, two and three years after people start taking antiviral treatment, so that we can understand how well the treatments are working over time,” said Professor Matthew Law from the Kirby Institute.

“The data among adults on treatment in our studies show that viral suppression was achieved in an estimated 79% of adults at one year, and 65% at three years. However, viral suppression is poorer among children, at an estimated 64% at one year and 59% at three years.”

Senior study author, Dr Azar Kariminia from the Kirby Institute, said there are unique barriers to achieving viral suppression for children and adolescents. “It can be challenging for them to take treatment regularly, and children rely on caregivers who are often having to manage their own medical needs. There are also a range of factors that stem from stigma and discrimination, including a fear of disclosing the child’s HIV status.”

For this study, the researchers analysed data from 21 594 children/adolescents and 255 662 adults from 148 sites in 31 countries who initiated treatment between 2010 and 2019.

Dr Annette Sohn, from amfAR’s TREAT Asia program, is Co Principal Investigator for IeDEA Asia-Pacific (along with Prof. Law). She says that “while there has been substantial progress in the global response to HIV, the needs of children and adolescents often fall behind those of adults. Our efforts must extend beyond ensuring access to paediatric medicines to address the social and developmental challenges they face in growing up with HIV if we are to achieve the WHO targets by 2030.”

Viral load testing is essential to find out whether HIV treatments are working effectively. It is recommended by WHO at six and 12 months following the initiation of treatment, and then every 12 months thereafter. While viral load testing is common in high-income countries, scaling up accessible viral load testing in resource-limited settings remains a challenge.

With Australian government funding, the Kirby Institute and the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR) are partnering with the PNG government and a consortium of partners are implementing a program called ‘ACT-UP PNG’ which will scale up HIV viral load testing in two provinces with high HIV rates.

“Our work is ensuring that infants and children are afforded the same access to testing and treatment as other people with HIV,” says Dr Janet Gare from the PNGIMR and a Co-Principal Investigator on ACT-UP-PNG.

Instead of doing viral load testing in distant laboratories, ACT-UP PNG provides same-day molecular point-of-care testing in HIV clinics.

“This brings HIV viral load testing closer to patients, which currently includes children aged 10 and older, and adolescents,” says Dr Gare. “However, we are also pioneering the implementation of a diagnostic platform that will allow the same access to timely HIV viral load testing and results for infants six to eight weeks of age, and children up to nine years, who are currently unable to be included in point-of-care methods.”

Scientia Associate Professor Angela Kelly-Hanku says that these technologies will make testing for viral suppression in infants and children easier.

“We cannot end AIDS without addressing the inequalities that exist between paediatric and adult HIV programs. Projects like ACT-UP make a real difference and bring us closer to achieving the UNAIDS targets.”

Source: University of New South Wales