SA Unveils Ambitious New HIV Campaign amid Aid Crisis

By Ufrieda Ho

Amid major disruptions caused by aid cuts from the United States government, the health department aims to enrol a record number – an additional 1.1 million – of people living with HIV on life-saving antiretroviral medicine this year. Experts tell Spotlight it can’t be business as usual if this ambitious programme is to have a chance of succeeding.

Government’s new “Close the Gap” campaign launched at the end of February has set a bold target of putting an additional 1.1 million people living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment by the end of 2025.

Around 7.8 million people are living with HIV in the country and of these, 5.9 million are on treatment, according to the National Department of Health. The target is therefore to have a total of seven million people on treatment by the end of the year. Specific targets have also been set for each of the nine provinces.

The initiative is aimed at meeting the UNAIDS 95–95–95 HIV testing, treatment and viral suppression targets that have been endorsed in South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB, and STIs 2023 – 2028. The targets are that by 2030, 95% of people living with HIV should know their HIV status, 95% of people who know their status should be on treatment, and 95% of people on treatment should be virally suppressed (meaning there is so little HIV in their bodily fluids that they are non-infectious).

Currently, South Africa stands at 96–79–94 against these targets, according to the South African National Aids Council (SANAC). This indicates that the biggest gap in the country’s HIV response lies with those who have tested positive but are not on treatment – the second 95 target.

But adding 1.1 million people to South Africa’s HIV treatment programme in just ten months would be unprecedented. The highest number of people who started antiretroviral treatment in a year was the roughly 730 000 in 2011. In each of the last five years, the number has been under 300 000, according to figures from Thembisa, the leading mathematical model of HIV in South Africa. According to our calculations, if South Africa successfully adds 1.1 million people to the HIV treatment programme by the end of 2025, the score on the second target would rise to just above 90%.

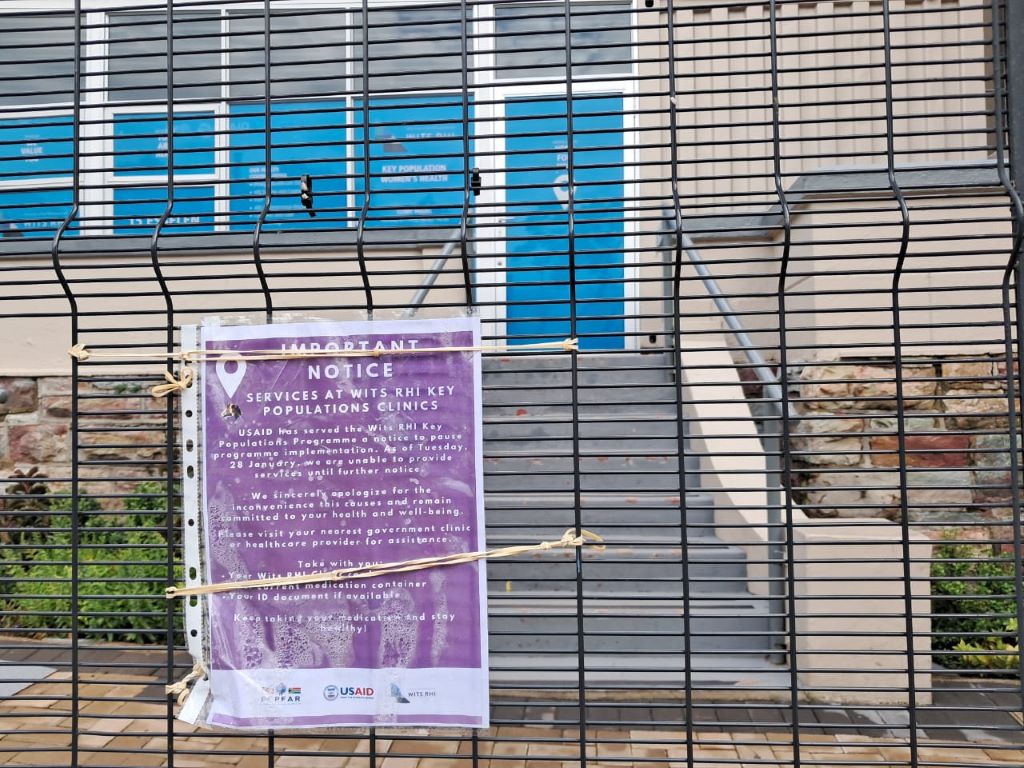

The ambitious new campaign launches at a moment of crisis in South Africa’s HIV response. Abrupt funding cuts from the United States government – the PEPFAR funding – has meant that the work of several service-delivery NGOs have ground to a halt in recent weeks.

These NGOs played an important role in getting people tested and in helping find people and supporting them to start and restart treatment. The focus of many of these NGOs was on people in marginalised but high-risk groups, including sex workers, people who use drugs and those in the LGBTQI community. As yet, government has not presented a clear plan for how these specialised services might continue.

“We will need bridging finance for many of these NGOs to contain and preserve the essential work that they were doing till we can confer these roles and responsibilities to others,” says Professor Francois Venter, of the Ezintsha Research Centre at the University of the Witwatersrand.

He says good investment in targeted funding for NGOs is a necessary buffer to minimise “risks to the entire South African HIV programme” and the looming consequences of rising numbers of new HIV cases, more hospitalisations, and inevitably deaths.

Disengaging from care

South Africa’s underperformance on the second 95 target is partly due to people stopping their treatment. The reasons for such disengagement from HIV care can be complex. Research has shown it is linked to factors like frequent relocations, which means people have to restart treatment at different clinics over and over. They also have to navigate an inflexible healthcare system. A systematic review identified factors including mental health challenges, lack of family or social support, long waiting times at clinics, work commitments, and transportation costs.

Venter adds that while people are disengaged from care, they are likely transmitting the virus. The addition of new infections for an already pressured HIV response contributes to South Africa’s sluggish creep forward in meeting the UNAIDS targets.

The health department has not been strong on locating people who have been “lost” to care, says Venter. This role was largely carried out by PEPFAR-supported NGOs that are now unable to continue their work due to the withdrawal of crucial US foreign aid.

Inexpensive interventions

Other experts working in the HIV sector, say the success of the Close the Gap campaign will come down to scrapping programmes and approaches that have not yielded success, using resources more efficiently, strategic investment, and introducing creative interventions to meet the service delivery demands of HIV patients.

Key among these interventions, is to improve levels of professionalism in clinics so patients can trust the clinics enough to restart treatment.

Professor Graeme Meintjes of the Department of Medicine at the University of Cape Town says issues like improving staff attitudes and updating public messaging and communications are inexpensive interventions that can boost “welcome back” programmes.

“The Close the Gap campaign must utilise media platforms and social media platforms to send out a clear message, so people know the risks of disengagement and the importance of returning to care. The longer someone interrupts their treatment and the more times this happens, the more they are at risk of opportunistic infections, severe complications, getting very sick and needing costly hospitalisations,” he says.

Clinics need to provide friendly, professional services that encourage people to return to and stay on treatment, Meintjes says, and services need to be flexible. These could include more external medicine pick-up points, scripts filled for longer periods, later clinic operating hours, and mobile clinic services.

“We need to make services as flexible as possible. People can’t be scolded for missing an appointment – life happens. Putting these interventions in place are not particularly costly, in fact it is good clinical practice and make sense in terms of health economics by avoiding hospitalisations that result from prolonged treatment interruptions,” he says.

The Close the Gap campaign, Meintjes adds, should reassure people that HIV treatment has advanced substantially over the decades. The drugs work well and now have far fewer side effects, with less risk of developing resistance. More patients are stable on the treatment for longer and most adults manage their single tablet once-a-day regime easily.

Insights from our experiences

Professor Linda-Gail Bekker, Chief Executive Officer at the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, says to get closer to the target of 1.1 million people on treatment by year-end will mean using resources better.

“Additional funding is always welcome, so are new campaigns that catalyse and energise. But we also need to stop doing the things we know don’t have good returns. For instance, testing populations of people who have been tested multiple times and aren’t showing evidence of new infections occurring in those populations,” she says.

There is also a need for better data collection and more strategic use of data, Bekker says. Additionally, she suggests a status-neutral approach, meaning that if someone tests positive, they are referred for treatment, while those who test negative are directed to effective prevention programmes, including access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for people at high risk of exposure through sex or injection drug use.

But Bekker adds: “We need to be absolutely clear; these people aren’t going to come to us in our health facilities, or we would have found them already. We have to do the work that many of the PEPFAR-funded NGOs were doing and that is going to the last mile to find the last patient and to bring them to care.”

She says the impact of the PEPFAR funding cuts can therefore not be downplayed. “The job is going to get harder with fewer resources that were specifically directed at solving this problem.”

Venter names another approach that has not worked. This, he says, is the persistence of treating HIV within an integrated health system. Overburdened clinics have simply not coped, he adds, with being able to fulfil the ideal of a “one-stop-shop” model of healthcare.

Citing an example, he says: “Someone might come into a clinic with a stomach ache and be vomiting, they might be treated for that but there’s no investigation or follow-up to find out if it might be HIV-related, for instance. And once that person is out of the door, they’re gone.”

Campaign specifics still lacking

The Department of Health did not answer Spotlight’s questions about funding for the Close the Gap campaign; what specific projects in the campaign will look like; or how clinics and clinic staff will be equipped or supported in order to find the 1.1 million people. There is also scant details of the specifics of the campaign online.

Speaking to the public broadcaster after the 25 February campaign launch, Health Minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi said South Africa is still seeing 150 000 new infections every year. He said they will reach their 1.1 million target through a province-by-province approach. He used the Eastern Cape as an example.

“When you look at the 1.1 million, it can be scary – it’s quite big. But if you go to the provinces – the Eastern Cape needs to look for 140 000 people. Then you come to their seven districts, that number becomes much less. So, one clinic could be looking for just three people,” he said.

Nelson Dlamini, SANAC’s communications manager, says the focus will be to bring into care 650 000 men, as men are known to have poor health-seeking habits. Added to this will be a focus on adolescents and children who are living with HIV.

He says funding for the Close the Gap campaign will not be shouldered by the health department alone.

“This is a multisectoral campaign. Other departments have a role to play, these include social development, basic education, higher education and training, etc, and civil society themselves,” Dlamini says.

The province-by-province approach to reach the target of finding 1.1 million additional people is guided by new data sources.

“Last year, SANAC launched the SANAC Situation Room, a data hub which pulls data from multiple sources in order for us to have the most accurate picture on the status of the epidemic,” says Dlamini.

These include the Thembisa and Naomi model outputs and data from the District Health Information System and Human Sciences Research Council, he says adding that SANAC is working to secure data sharing agreements with other sectors too.

Dlamini however says the health department, rather than SANAC, will provide progress reports on the 10-month project.

Republished from Spotlight under a Creative Commons licence.

Read the original article.