A New Heart Failure Treatment Targets Abnormal Hormone Activity

Scientists have discovered a potential new treatment for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart disease that is notoriously difficult to treat. The diseased heart cells were found to have high levels of glucagon activity, a pancreatic hormone that raises blood glucose levels. The scientists then demonstrated that a drug that blocks the hormone’s activity can significantly improve heart function.

In heart failure, which is considered a global pandemic, the heart can no longer pump blood effectively. Globally, an estimated 64 million people live with this condition with HFpEF accounting for around half of the cases.

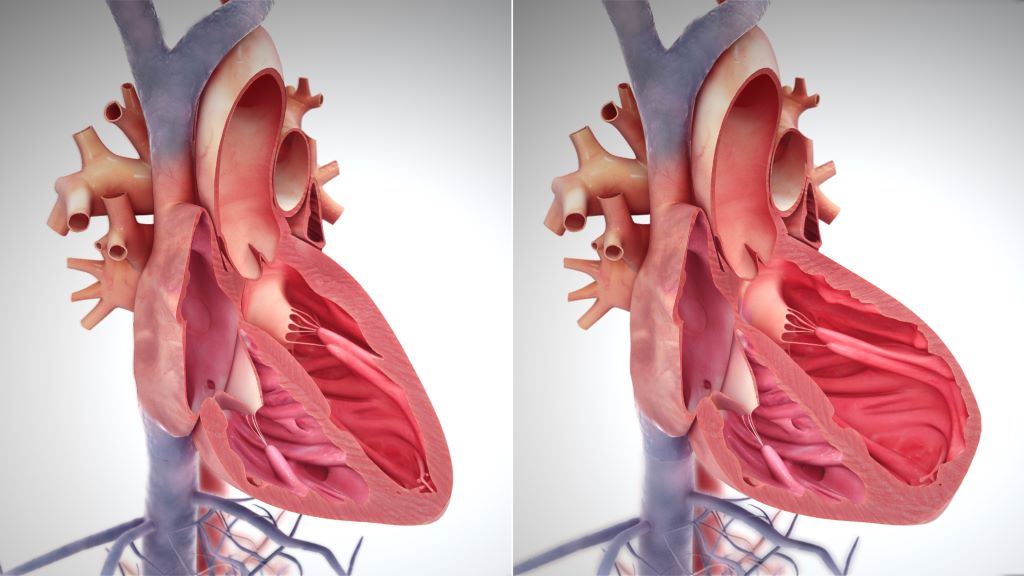

In HFpEF, the heart can pump normally but its muscles are too stiff to relax to re-fill the chambers with blood properly. It is often seen in older adults and people with multiple risk factors including high blood pressure (hypertension), obesity and diabetes. They typically have symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue and reduced ability to exercise. This is unlike heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), where heart muscle is weakened and pumping volume reduced.

There have been studies on how the heart is stressed by hypertension and metabolic diseases associated with obesity, such as diabetes, but these have been done in isolation of each other. This latest study, which was published in Circulation Research, addresses this gap by taking into account both stressors, revealing for the first time, the molecular pathway that contributes to HFpEF progression.

In pre-clinical studies, the team of scientists, which included collaborators from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, University of Toronto and University of North Carolina School of Medicine, investigated how stress from hypertension affected lean hearts versus diabetic/obese ones. In their findings, the lean models developed heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), typically observed in hypertensive patients. The obese models however, developed heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), proving that a combination of stressors give rise to the disease and providing a good model for further studies.

Using advanced single-cell RNA-sequencing technologies, the scientists were then able to study the expression of every detected gene in every single heart cell, allowing them to uncover specific genetic variations in cells associated with HFpEF. The scientists found that in the obese models, the most active genes were the ones driving the activity of glucagon.

Professor Wang Yibin, Director of the Cardiovascular & Metabolic Disorders Programme at Duke-NUS and senior author of the study, said:

“Under stress conditions such as high blood pressure and metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes, we found that glucagon signalling becomes excessively active in heart cells. This heightened activity contributes to the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) by increasing heart stiffness and impairing its ability to relax and fill with blood.”

The team then tested a drug that blocks the glucagon receptor in a pre-clinical model of HFpEF and found significant improvements in heart function, including reduced heart stiffness, enhanced relaxation, improved blood filling capacity and overall better heart performance.

Assistant Professor Chen Gao from the Department of Pharmacology, Physiology and Neurobiology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; and the study’s first author, said:

“Our study shows strong evidence that a glucagon receptor blocker could work well to treat HFpEF. Repurposing this drug, which is already being tested in clinical trials for diabetes, could bypass the lengthy drug development process and provide quicker and more effective relief to millions of heart patients.”

Professor Patrick Tan, Senior Vice-Dean for Research at Duke-NUS, commented:

“With our ageing population, there will likely be more patients with multiple conditions, including heart failure, diabetes and hypertension, presenting a significant challenge to health systems. Uncovering the synergistic impact of such illnesses and their underlying mechanisms is key to better understanding the complex process of heart failure and developing an effective treatment for the disease.”

The researchers hope to work with clinical partners to conduct clinical trials to test the glucagon receptor blocker in humans with HFpEF. If these succeed, it could become one of the first effective treatments for this challenging condition, significantly improving the quality of life for millions worldwide.

Source: Duke University