SARS-CoV-2 Does Not Alter Human DNA

Despite controversial claims, the SARS-CoV-2 virus likely does not integrate its genetic material into the genes of humans, according to a study published in the Journal of Virology.

A prior study reported the virus’s genetic material was found to have integrated into human DNA in cells in petri dishes, though the scientists conducting the newer research now say this was resulted from genetic artefacts in the testing.

Study co-lead author Majid Kazemian, a Purdue University assistant professor of biochemistry and computer science, said that this finding has two important implications.

“Relatively little is known about why some individuals persistently test positive for the virus even long after clearing the infection,” he explained. “This is important because it’s not clear whether such individuals have been re-infected or whether they continue to be infectious to others. So-called ‘human genome invasion’ by SARS-CoV-2 has been suggested as an explanation for this observation, but our data do not support this case.

“If the virus was able to integrate its genetic material into the human genome, that could have meant that any other mRNA could do the same. But because we have shown that this is not supported by current data, this should allay any concerns about the safety of mRNA vaccines,” he concluded.

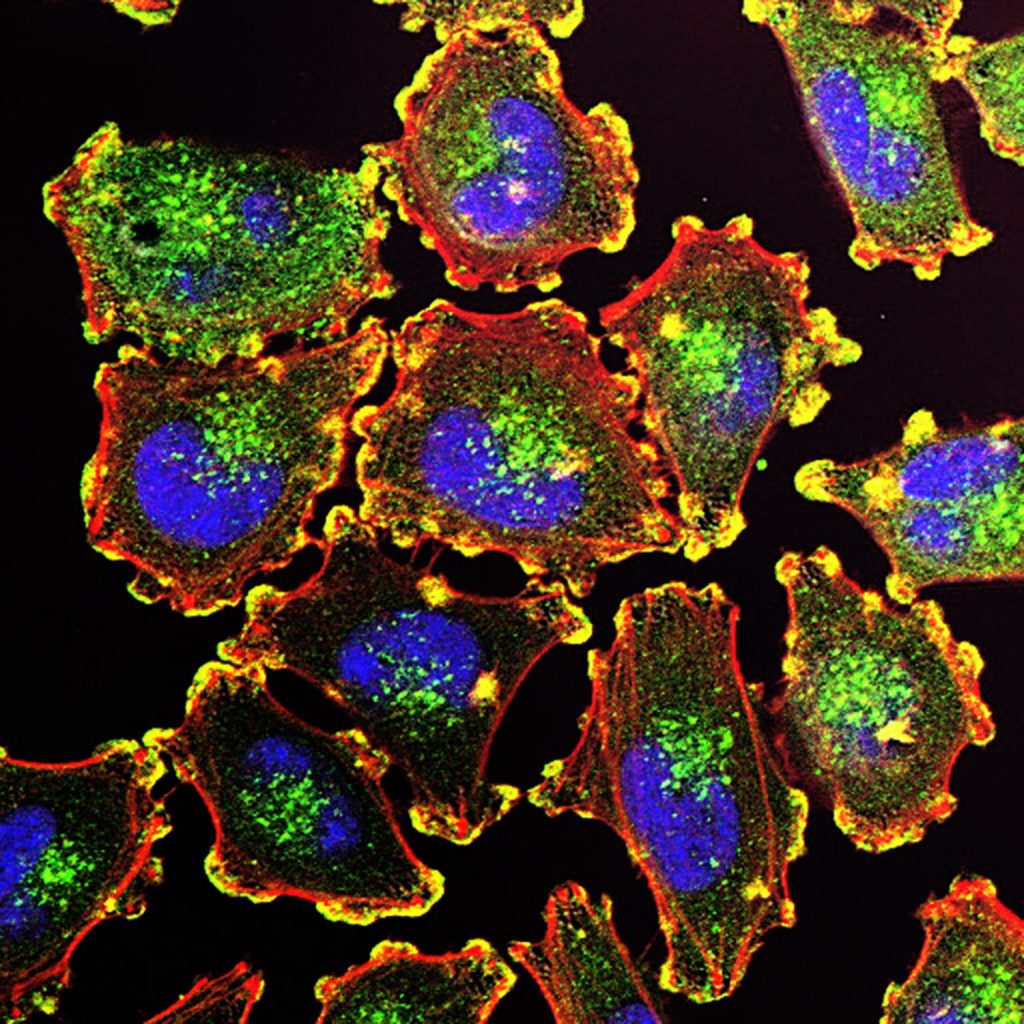

It is indeed possible for virus genetic material to be incorporated into the DNA of humans and other animals, which are referred to as ‘chimeric events’. These have happened over many millions of years; human DNA contains approximately 100 000 pieces of ‘fossil DNA’ from viruses that have been accumulated throughout our evolution, accounting for nearly 10% of the genetic material in our cells. Some viral fragments even play a role in diseases such as cancer.

Recent scientific journal articles have raised controversy by claiming that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can also cause these chimeric events. Even before this study demonstrated it was not the case, the researchers suspected it was unlikely, said co-lead author Dr Ben Afzali, an Earl Stadtman Investigator of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

“While an earlier study suggested that, in cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, genetic material from the virus copied and pasted itself into human DNA, our group thought this seemed unlikely,” Dr Afzali said. “SARS-CoV-2, like HIV, has its genetic material in the form of RNA but, unlike HIV, does not have the machinery to convert the RNA into DNA. SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely to paste itself into the genome and coronaviruses, in general, does not go near human DNA. As our study shows, we find it highly improbable that SARS-CoV-2 could integrate into the human genome.”

Christiane Wobus, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan Medical School, another co-lead author on the study, said that the collective understanding of RNA viruses is that SARS-CoV-2 integrating into the human genome was extremely unlikely, it was still worth asking the question.

“Unexpected findings in science—when confirmed independently—lead to paradigm shifts and propel fields forward. Therefore, it is good to be open-minded and examine unexpected results carefully, which I believe we did in our study,” she said. “However, we did not find conclusive evidence for SARS-CoV-2 integration, but instead showed that during the RNA sequencing methodology, chimeras are produced at a very low level as an artifact of the laboratory technique.”

To examine any possible integration event, the researchers came up with a novel technique involving extraction the genetic material from infected cells and then boosting the amount of the genetic material 30-fold. With any chimeric events in the host cell DNA, these bits of genetic material from SARS-CoV-2 would have also increased those by 30. The data did not show this.

“We found the frequency of host-virus chimeric events was, in fact, not greater than background noise,” Kazemian stated. “When we enriched the SARS-CoV-2 sequences from the bulk RNA of infected cells, we found that the chimeric events are, in all likelihood, artifacts. Our work does not support the claim that SARS-CoV-2 fuses or integrates into human genomes.”

Source: Medical Xpress

Journal information: Bingyu Yan et al, Host-virus chimeric events in SARS-CoV2 infected cells are infrequent and artifactual, Journal of Virology (2021). DOI: 10.1128/JVI.00294-21