An Arthritis Drug Might Unlock Lasting Relief from Epilepsy and Seizures

A drug typically prescribed for arthritis halts brain-damaging seizures in mice that have a condition like epilepsy, according to researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The drug, called tofacitinib, also restores short-term and working memory lost to epilepsy in the mice and reduces inflammation in the brain caused by the disease.

If the drug proves viable for human patients, it would be the first to provide lasting relief from seizures even after they stopped taking it.

“It ticks all the boxes of everything we’ve been looking for,” says Avtar Roopra, a neuroscience professor in the UW–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and senior author of the study, which appears in Science Translational Medicine.

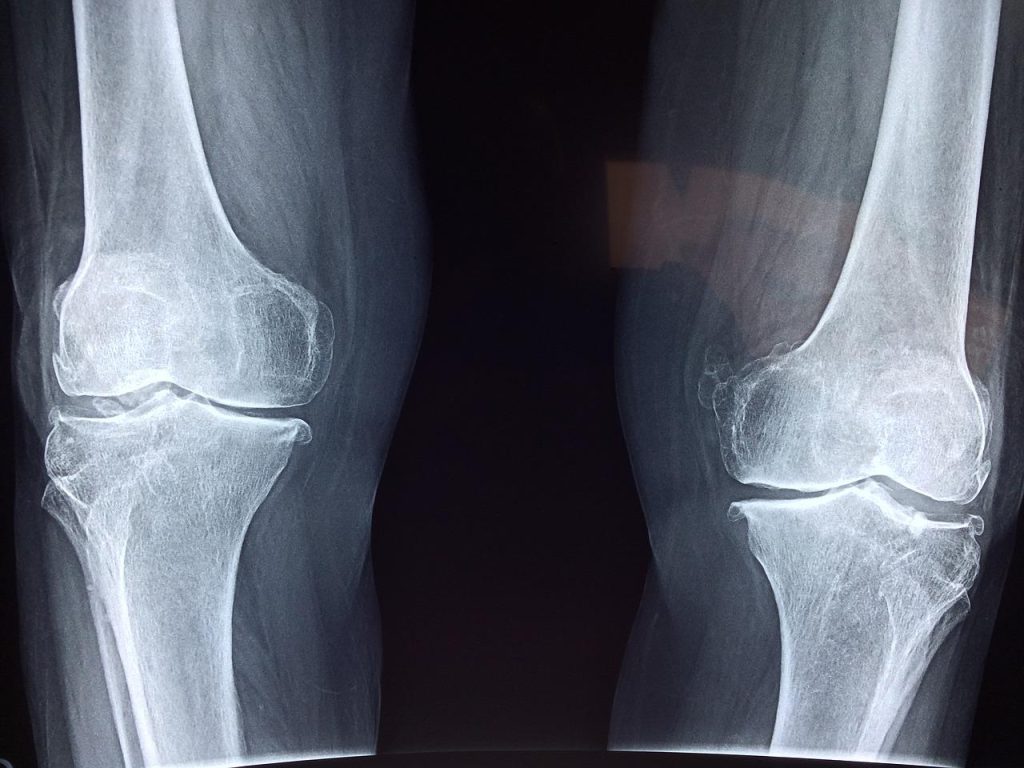

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological diseases, afflicting more than 50 million people around the world. While there are many known causes, the disease often appears after an injury to the brain, like a physical impact or a stroke.

Some days, months or even years after the injury, the brain loses the ability to calm its own activity. Normally balanced electrical activity through the brain goes haywire.

“The system revs up until all the neurons are firing all the time, synchronously,” says Roopra. “That’s a seizure that can cause massive cell death.”

And the seizures repeat, often at random intervals, forever. Some drugs have been useful in addressing seizure symptoms, protecting patients from some of the rampant inflammation and memory loss, but one-third of epilepsy patients do not respond to any known drugs, according to Olivia Hoffman, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in Roopra’s lab. The only way to stop the most damaging seizures has been to remove a piece of the brain where disruptive activity starts.

On their way to identifying tofacitinib’s potential in epilepsy, Hoffman and co-authors used relatively new data science methods to sift through the way thousands of genes were expressed in millions of cells in the brains of mice with and without epilepsy. They found a protein called STAT3, key to a cell signaling pathway called JAK, at the centre of activity in the seizure-affected mouse brains.

“When we did a similar analysis of data from brain tissue removed from humans with epilepsy, we found that was also driven by STAT3,” Hoffman says.

Meanwhile, Hoffman had unearthed a study of tens of thousands of arthritis patients in Taiwan aimed at describing other diseases associated with arthritis. It turns out, epilepsy was much more common among those arthritis patients than people without arthritis — but surprisingly less common than normal for the arthritis patients who had been taking anti-inflammatory drugs for more than five-and-a-half years.

“If you’ve had rheumatoid arthritis for that long, your doctor has probably put you on what’s called a JAK-inhibitor, a drug that’s targeting this signaling pathway we’re thinking is really important in epilepsy,” Hoffman says.

The UW researchers ran a trial with their mice, dosing them with the JAK-inhibitor tofacitinib following the administration of a brain-damaging drug that puts them on the road to repeated seizures. Nothing happened. The mice still developed epilepsy like human patients.

Remember, though, that epilepsy doesn’t often present right after a brain-damaging event. It can take years. In the lab mice, there’s usually a lull of weeks of relatively normal time between the brain damage and what the researchers call “reignition” of seizures. If it’s not really epilepsy until reignition, what if they tried the drug then? They devised a 10-day course of tofacitinib to start when the mouse brains fell out of their lull and back into the chaos of seizures.

“Honestly, I didn’t think it was going to work,” Hoffman says. “But we believe that initial event sort of primes this pathway in the brain for trouble. And when we stepped in at that reignition point, the animals responded.”

The drug worked better than they could have imagined. After treatment, the mice stayed seizure-free for two months, according to the paper. Collaborators at Tufts University and Emory University tried the drug with their own mouse models of slightly different versions of epilepsy and got the same, seizure-free results.

Roopra’s lab has since followed mice that were seizure-free for four and five months. And their working memory returned.

“These animals are having many seizures a day. They cannot navigate mazes. Behaviourally, they are bereft. They can’t behave like normal mice, just like humans who have chronic epilepsy have deficits in learning and memory and problems with everyday tasks,” Roopra says. “We gave them that drug, and the seizures disappear. But their cognition also comes back online, which is astounding. The drug appears to be working on multiple brain systems simultaneously to bring everything under control, as compared to other drugs, which only try to force one component back into control.”

Because tofacitinib is already FDA-approved as safe for human use for arthritis, the path from animal studies to human trials may be shorter than it would be for a brand-new drug. The next steps toward human patients largely await NIH review of new studies, which have been paused indefinitely amid changes at the agency.

For now, the researchers are focused on trying to identify which types of brain cells are shifted back to healthy behavior by tofacitinib and on animal studies of even more of the many types of epilepsy. Hoffman and Roopra have also filed for a patent on the use of the drug in epilepsy.

Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison