Indoor Air Pollution Linked to Pneumonia in Children

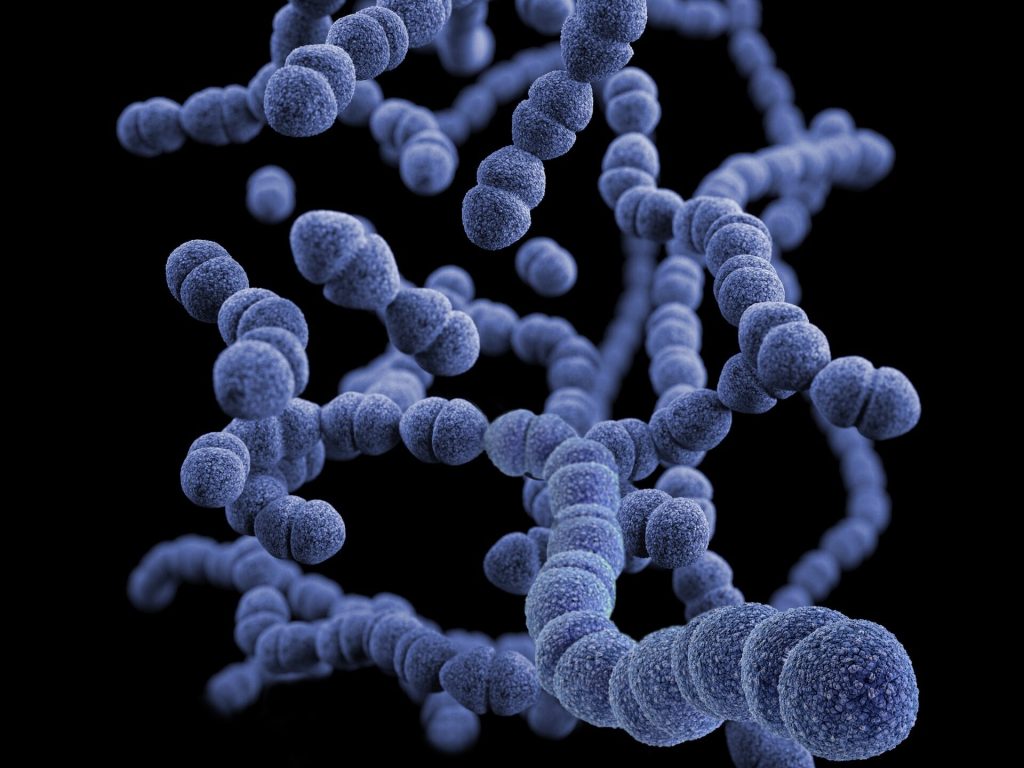

A new study published in The Lancet Global Health, highlights the impact indoor air pollution can have on the development of child pneumonia, showing that increases in airborne particulate matter results in greater carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen causing more than two million deaths per year; more than HIV/AIDS, measles and malaria combined, but it is also part of the normal microbial community of the nasopharynx. It is the leading cause of death due to infectious disease in children under five years of age; in sub-Saharan Africa, the burden of pneumococcal carriage and pneumonia is especially high.

Household air pollution from solid fuels increases the risk of childhood pneumonia. Nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae is a necessary step in the development of pneumococcal pneumonia. More than 2.6 billion people are exposed to household air pollution worldwide. Inefficient indoor biomass burning is estimated to cause 3.8 million premature deaths annually and approximately 45% of all pneumonia deaths in children aged younger than five years. However, a causal pathway between household air pollution and pneumonia had not yet been identified.

In order to understand the connection between exposure to household air pollution and the risk of childhood pneumonia researchers from the UK, Malawi and the United States conducted the MSCAPE (Malawi Streptococcus pneumoniae Carriage and Air Pollution Exposure) study embedded in the ongoing CAPS (Child And Pneumonia Study) trial. The MSCAPE study assessed the impact of PM2.5, the single most important health-damaging pollutant in household air pollution, on the prevalence of pneumococcal carriage in a large sample of 485 Malawian children.

Through exposure-response analysis, a statistically significant 10% increase in risk of S. pneumoniae carriage in children was observed for a unit increase (deciles) of exposure to PM2.5 (ranging from 3.9 μg/m³ to 617.0 μg/m³).

Dr. Mukesh Dherani, the study principal investigator, indicated: “This study provides us with greater insight into the impact household air pollution can have on the development of child pneumonia. These findings provide important new evidence of intermediary steps in the causal pathway of household air pollution exposure to pneumonia and provide a platform for future mechanistic studies.”

Study author Professor Dan Pope said: “Moving forward further studies, particularly new randomized controlled trials comparing clean fuels (e.g. liquefied petroleum gas) with biomass fuels, with detailed measurements of PM2.5 exposure, and studies of mechanisms underlying increased pneumococcal carriage, are required to strengthen causal evidence for this component of the pathway from household air pollution exposure to ALRI in children.”

Professor Nigel Bruce, co-principal investigator, stated: “This study provides further important evidence that emphasises the need to accelerate to cleaner fuels, such as LPG, which are now being promoted by many governments across the continent in order to meet SDG7 by 2030.”

Source: University of Liverpool