Reducing the Rebleeding Risk from Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding

In a study published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, clinical investigators found that the five-year risk of rebleeding in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding was found to be as high as 41.7%, but capsule endoscopy examinations and subsequent interventions substantially reduced the risk. Factors such as anticoagulant use were also found to be independent predictors of rebleeding risk.

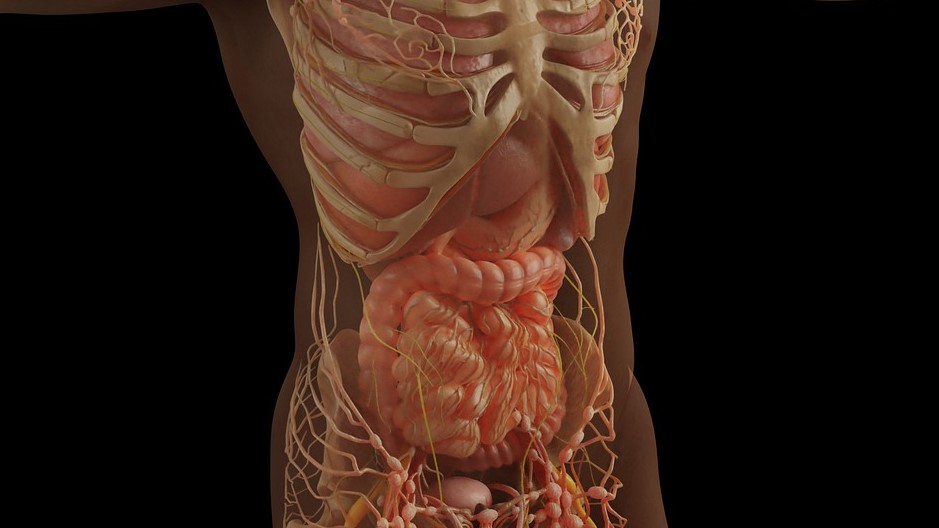

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as gastrointestinal bleeding from a source that cannot be identified on upper or lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. OGIB is considered an important indication for capsule endoscopy (CE). CE is particularly useful for the detection of vascular and small ulcerative lesions, conditions frequently associated with OGIB.

Previous studies have shown that patients with severe comorbidities have a higher rate of positive CE findings (observations of mucosal breaks, vascular lesions, tumours, or blood retention) for OGIB. Additionally, for OGIB in which the initial CE fails to identify bleeding lesions, repeated CE can detect lesions at a higher rate. However, there have been no reports with a sufficiently large number of cases on the long-term outcomes of OGIB detected by CE and the risk of rebleeding.

To fill this knowledge gap, investigators followed up on 389 patients who underwent CE as their initial small intestinal examination for OGIB and evaluated the risk of rebleeding over the long term. In addition, the team evaluated the risk of rebleeding in OGIB, in which no source of rebleeding was found in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, including the small intestine.

The overall cumulative rebleeding rate during the five years after CE was 41.7%. In patients with positive CE findings, the cumulative rebleeding rate was 48.0%. The cumulative rebleeding rate in patients who had therapeutic intervention resulting from positive CE findings was 31.8%.

Furthermore, overt OGIB, anticoagulants, positive balloon-assisted enteroscopy after CE, and iron supplements without therapeutic intervention were found to be independent predictors of rebleeding. Among the components of an index assessing the severity of complications, liver cirrhosis was an independent predictor associated with rebleeding in patients with OGIB.

“If capsule endoscopy can be used to properly diagnose and lead to therapeutic intervention, the risk of rebleeding can be reduced,” concluded study leader Dr Otani. “Even if the endoscopy does not detect any lesions, adequate follow-up is necessary. Here at Osaka Metropolitan University, we have been utilising this tool clinically since its early days and have accumulated some of the world’s leading clinical data. This study revealed a high rebleeding rate in OGIB patients and clarified the effects of rebleeding predictors and therapeutic intervention. We have high expectations that this will lead to better medical care in the future.”

Source: Osaka Metropolitan University