A Potential Stool Test for Endometriosis also Suggests an IBD Link

Promising findings by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and collaborating institutions could lead to the development of a non-invasive stool test and a new therapy for endometriosis, a painful condition that affects nearly 200 million women worldwide. The study appeared in the journal Med.

“Endometriosis develops when lining inside the womb grows outside its normal location, for instance attached to surrounding intestine or the membrane lining the abdominal cavity. This typically causes bleeding, pain, inflammation and infertility,” said corresponding author Dr Rama Kommagani, associate professor in the Department of Pathology and Immunology at Baylor. “Generally, it takes approximately seven years to detect endometriosis and is often diagnosed incorrectly as a bowel condition. Thus, delayed diagnosis, together with the current use of invasive diagnostic procedures and ineffective treatments underscore the need for improvements in the management of endometriosis.”

“Our previous studies in mice have shown that the microbiome, the communities of bacteria living in the body, or their metabolites, the products they produce, can contribute to endometriosis progression,” Kommagani said. “In the current study, we took a closer look at the role of the microbiome in endometriosis by comparing the bacteria and metabolites present in stools of women with the condition with those of healthy women. We discovered significant differences between them.”

The findings suggested that stool metabolites found in women with endometriosis could be the basis for a non-invasive diagnostic test as well as a potential strategy to reduce disease progression.

The researchers discovered a combination of bacterial metabolites that is unique to endometriosis. Among them is the metabolite called 4-hydroxyindole. “This compound is produced by ‘good bacteria,’ but there is less of it in women with endometriosis than in women without the condition,” said first author Dr Chandni Talwar, postdoctoral associate in Kommagani’s lab.

“These findings are very exciting,” Talwar said. “There are studies in animal models of the disease that have shown specific bacterial metabolite signatures associated with endometriosis. Our study is the first to discover a unique metabolite profile linked to human endometriosis, which brings us closer to better understanding the human condition and potentially identifying better ways to manage it.”

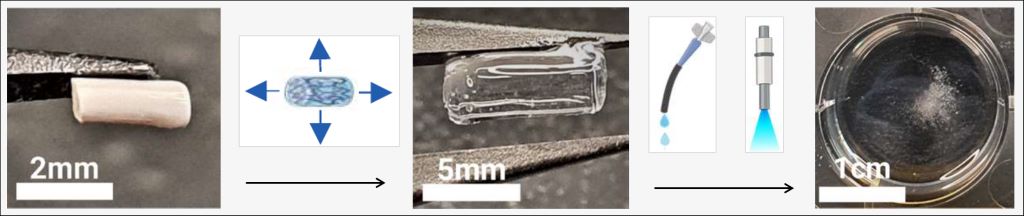

Furthermore, extensive studies also showed that administering 4-hydroxyindole to animal models of the disease prevented the initiation and progression of endometriosis-associated inflammation and pain.

“Interestingly, our findings also may have implications for another condition. The metabolite profile we identified in endometriosis is similar to that observed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), revealing intriguing connections between these two conditions,” Kommagani said. “Our findings support a role for the microbiome in endometriosis and IBD.”

The researchers are continuing their work toward the development of a non-invasive stool test for endometriosis. They are also conducting the necessary studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 4-hydroxyindole as a potential treatment for this condition.

Source: Baylor College of Medicine