Causes of Fevers of Unknown Origin in sub-Saharan Africa

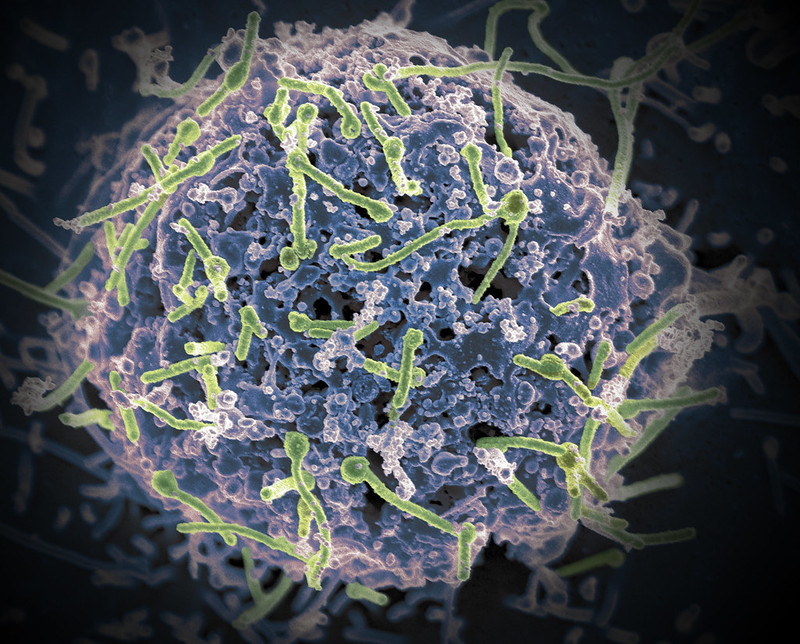

A new retrospective, laboratory-based observational study provides detailed insights into the causes of fevers of unknown origin in sub-Saharan Africa. Researchers examined 550 patients from Guinea who developed a persistent fever at the time of the major Ebola outbreak in 2014, but tested negative for the Ebola virus on site. The goal was to use modern diagnostic methods to better understand the underlying infectious diseases. The study is published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Fever is a common symptom of many diseases, including infections, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. When the cause of a persistent fever remains unclear despite extensive investigation, it is referred to as fever of unknown origin (FUO). Approximately half of all FUO cases worldwide remain undiagnosed. In sub-Saharan Africa, malaria is often suspected and treated without laboratory confirmation or further investigation. However, 90 million pediatric hospitalisations per year in sub-Saharan Africa are due to fevers not caused by malaria but by other infections, often due to various bacteria and viruses.

A research team from the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, in collaboration with scientists from Guinea and Slovakia, conducted a retrospective observational study to thoroughly investigate the pathogen diversity of patients from Guinea with fever of unknown cause during a major Ebola outbreak in 2014. They combined epidemiological, phylogenetic, molecular, serological and clinical data.

Using serologic tests, PCR and high-throughput sequencing, at least one pathogen was detected in 275 of 550 patients. In addition to the expected malaria parasite Plasmodium, pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella and Klebsiella strains were detected in almost one fifth of the patients. The frequent detection of resistance to so-called first-line antibiotics in the samples examined and the high rate of co-infections were also worrying: One in five infected patients had multiple infections at the same time. Pathogens causing malaria and bacterial sepsis were particularly common, occurring together in 12% of adults and 12.5% of children.

Infections with highly pathogenic viruses were also common: Yellow fever, Lassa and Ebola viruses were detected by RT-PCR in about six percent of patients. Of particular note was the detection of infection with Orungo virus, a little-known pathogen for which there are no robust assays. Using immunofluorescence assays, the researchers also identified IgM antibodies against several viruses, including Dengue, West Nile and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever viruses, in patients who were PCR-negative.

“In Africa, febrile illnesses of unknown cause are often recognized and treated as malaria without further diagnosis. In our study, we were able to detect a pathogen in about half of all patients with FUO, including bacterial pathogens that cause sepsis, haemorrhagic fever viruses including Ebola, and, as expected, various strains of the malaria parasite Plasmodium,” explains the study’s last author Prof. Jan Felix Drexler.

The findings underscore the urgent need to further strengthen laboratory capacity in sub-Saharan Africa. Early detection of the infectious causes of FUO is critical for patient care, effective response to outbreaks, and development of regionally appropriate diagnostics.

“Our results show that regionally adapted treatment regimens should be discussed, that quality control in the context of outbreaks needs to be strengthened, and that knowledge of the pathogen spectrum can guide targeted strengthening of regional laboratories and translational research in the sense of point-of-care tests,” Drexler summarises the results of the study.