20 Years of Data Proves Safety of Islet Cell Transplantation

In a paper published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, researchers report that their long-running islet cell transplant programme has shown that is safe and helps control diabetes for up to 20 years.

The researchers reported on patient survival, graft survival, insulin independence and protection from life-threatening hypoglycaemia for 255 patients who have received a total of more than 700 infusions of islets at the University of Alberta Hospital over the past two decades.

“We’ve shown very clearly that islet transplantation is an effective therapy for patients with difficult-to-control Type 1 diabetes,” said Professor James Shapiro at the University of Alberta. “This long-term safety data gives us confidence that we are doing the right thing.”

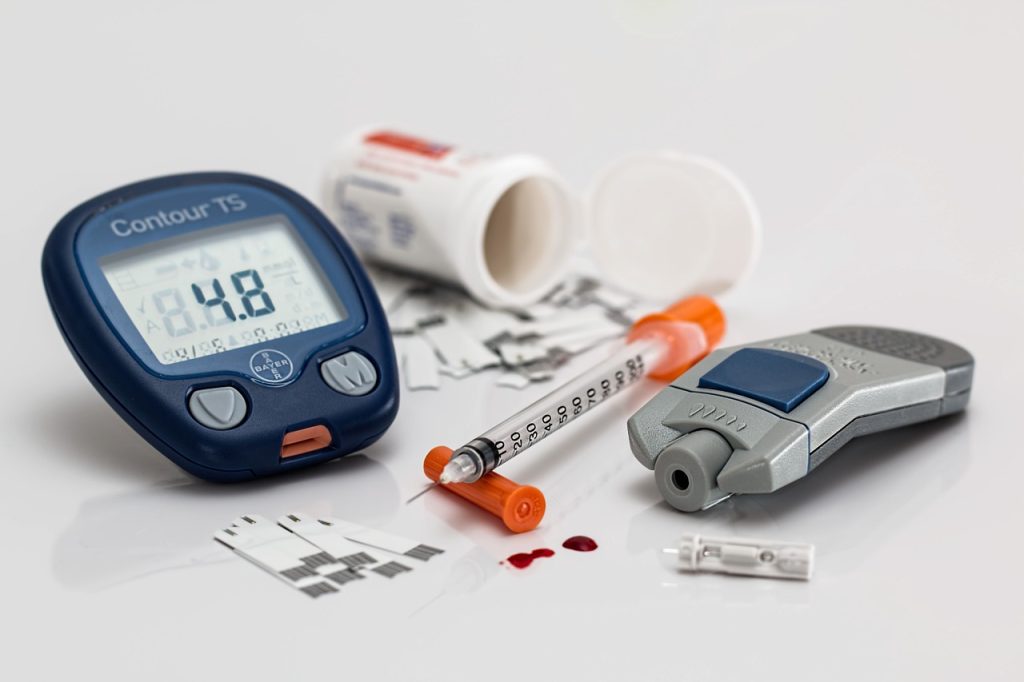

In Type 1 diabetes, the immune system mistakenly destroys the cells within the insulin-producing islets so patients have to take insulin by injection. Patients with hard-to-control diabetes face dangerous hypo- or hyperglycaemia and long-term complications.

Between March 1999 and October 2019, 255 patients received islet transplants by infusion into their livers. Seventy per cent of the grafts survived for a median time of nearly six years. The researchers reported that a combination of two anti-inflammatory medications given during the first two weeks following transplant significantly increased long-term islet function.

The transplant recipients have to take lifelong immunosuppression drugs, which in some cases lead to skin cancer or infection, but most such complications were not fatal during the study period.

After two or more islet infusions and a median time of 95 days following the first transplant, 79% of the recipients could go off insulin. A year later, 61% remained insulin-independent, 32% at five years and 8% after 20 years, the researchers reported. Even though most patients had to start taking insulin again, doses were generally much smaller and diabetes control was improved.

“Being completely free of insulin is not the main goal,” said Prof Shapiro. “It’s a big bonus, obviously, but the biggest goal for the patient — when their life has been incapacitated by wild, inadequate control of blood sugar and dangerous lows and highs — is being able to stabilise. It is transformational.”

With trials ongoing in other countries, Prof Shapiro will continue to focus on finding a more plentiful supply of islet cells to replace the current reliance on deceased donors. Human trials have already shown success using stem cells programmed to produce insulin. Trials have just started to transplant cells that have been gene edited to make them invisible to the immune system.

“Islet transplant as it exists today isn’t suitable for everybody, but it shows very clear proof of concept that if we can fix the supply problem and minimize or eliminate the anti-rejection drugs, we will be able to move this treatment forward and make it far more available for children and adults with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the future,” said Shapiro.

Source: University of Alberta