Why Antidepressants Take Weeks to Provide Relief

The findings of a study published in Science Translational Medicine paint a new picture of how current antidepressant drugs work and suggest a new drug target in depression. As with most drugs, antidepressants were developed through trial and observation. Some 40% of patients with the disorder don’t respond adequately to the drugs, and when they do work, antidepressants take weeks to provide relief. Why this is has remained largely a mystery.

To figure out why these drugs have a delayed onset, the team examined a mouse model of chronic stress that leads to changes in behaviours controlled by the hippocampus. The hippocampus is vulnerable to stress and atrophies in people with major depression or schizophrenia. Mice exposed to chronic stress show cognitive deficits, a hallmark of impaired hippocampal function.

“Cognitive impairment is a key feature of major depressive disorder, and patients often report that difficulties at school and work are some of the most challenging parts of living with depression. Our ability to model cognitive impairment in lab mice gives us the chance to try and understand how to treat these kinds of symptoms,” said Professor Dane Chetkovich, MD, PhD, who led the study.

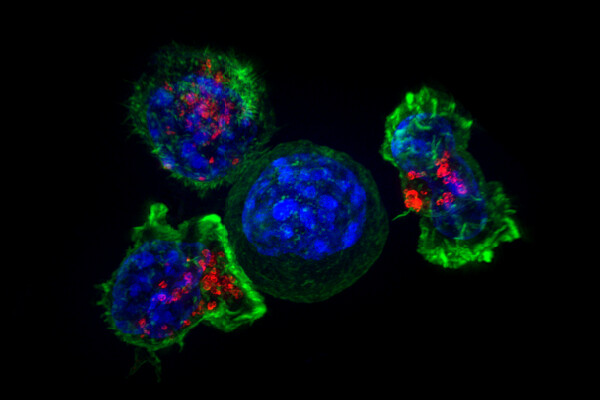

The study focussed on an ion transporter channel in nerve cell membranes known as the HCN channel. Previous work has shown HCN channels have a role in depression and separately to have a role in regulation of cognition. According to the authors, this was the first study to explicitly link the two observations.

Examination of postmortem hippocampal samples led the team to establish that HCN channels are more highly expressed in people with depression. HCN channel activity is modulated by a small signaling molecule called cAMP, which is increased by antidepressants. The team used protein receptor engineering to increase cAMP signaling in mice and establish in detail the effects this has on hippocampal HCN channel activity and, through that connection, on cognition.

Turning up cAMP was found to initially increase HCN channel activity, limit the intended effects of antidepressants and negatively impact cognition (as measured in standard lab tests).

However, a total reversal took place over a period of some weeks. Previous work by the researchers had established that an auxiliary subunit of the HCN channel, TRIP8b, is essential for the channel’s role in regulating animal behaviour. The new study shows that, over weeks, a sustained increase in cAMP starts to interfere with TRIP8b’s ability to bind to the HCN channel, thereby quieting the channel and restoring cognitive abilities.

“This leaves us with acute and chronic changes in cAMP, of the sort seen in antidepressant drug therapy, seen here for the first time to be regulating the HCN channel in the hippocampus in two distinct ways, with opposing effects on behaviour,” Prof Chetkovich said. “This appears to carry promising implications for new drug development, and targeting TRIP8b’s role in the hippocampus more directly could help to more quickly address cognitive deficits related to chronic stress and depression.”

Source: Vanderbilt University