Spiralling Costs Squeezing Medical Schemes – and Where does This Leave NHI?

Pressure from ageing populations, stagnant growth and growing medical costs will mean that medical aid schemes will make above-inflation rate hikes, reveals Momentum Health marketing officer Damian McHugh. He made the comments at Momentum Health Solutions’ virtual Healthcare Insights Summit on Tuesday (30 July), where he also noted that the same demands on medical funds are serving to put NHI even further out of reach, estimating a budget of some R1.3 trillion.

If one take’s McHugh’s figures and projects into the coming years, these above-inflation hikes make the target an ever increasing-one, steadily sending the current estimates even further from the realms of affordability. This is a situation which national health schemes of far wealthier countries are now encountering.

This comes as the Council for Medical Schemes advised the 1st of August of inflation plus “reasonable utilisation estimates” resulting in a recommendation to keep under 8.5%. But it given the pressures on medical aid schemes, this is unlikely to be adhered to, as last year already saw increases in excess of this.

Medical aid cost pressures

The CMS acknowledged that above-inflation medical cost increases are inevitable due to “unique industry factors such as technological advancement, the ageing population, and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases.”

Last year, Discovery Health Medical Scheme (DHMS) announced a weighted average increase of 7.5%, for 2024 – but its comprehensive “premium” segment rose by 13%. Both Momentum and BestMed announced weighted increases of 9.6% for 2024, while Bonitas managed to contain its increases to 6.9% (though its comprehensive cover rose to 9.6%). MediHelp surged to 15.96%, though it justified this increase as its options were the lowest-priced on the market.

Medical aid scheme growth is slow, at best around 0.5% per annum, while there is considerable pressure on subscriber income. Low income brackets only spend around 4% on healthcare, while middle and high income brackets spent 6% and 7%, respectively.

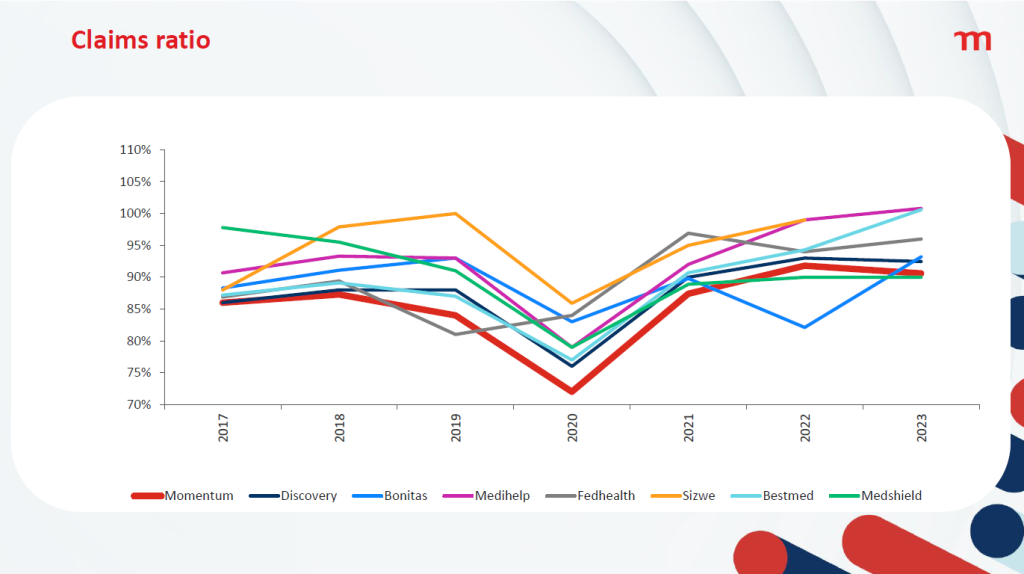

But with claims on the increase, many medical aids are having to tap into reserves and reducing solvency. Many medical aids are running close to 100% claims ratio – obviously a very bad situation for them to find themselves in.

These cost pressures result in a reduction in benefits, with the burden being shifted by reducing day-to-day benefits and members moving to Efficiency Discount Options (EDOs) – in turn, reducing the risk contribution income received by the schemes.

Rate hikes inevitable

In its recommended guidelines for 2025 released in Circular 35 of 2024, the CMS advised that medical aid schemes limit their contribution increases in line with CPIThis was based on the Reserve Bank’s latest inflation forecast which expects headline inflation to average 4.4% and 4.5% in 2025 and 2026, respectively. With last year’s estimated of an additional 3.2% to 3.8%, that works out to about 8.5%. But the CMS noted that medical aid schemes have historically had increases in excess of CPI+4%.

The COVID pandemic bucked the trend, resulting in – though many medical aid schemes saw record profits as procedures were deferred. Price increases were deferred, with increases kept below inflation for 2021 and 2022, with an uptick in 2023.

McHugh pointed out that growth in medical aid schemes has remained largely flat, and the ageing of the insured lives was linked to increasing claims costs as health problems became more complex. He revealed that claims costs per life had risen from about R15 000 in 2017 to R21 000 in 2022. This, spread across the population of South Africa, would require an NHI budget of R1.3 trillion.

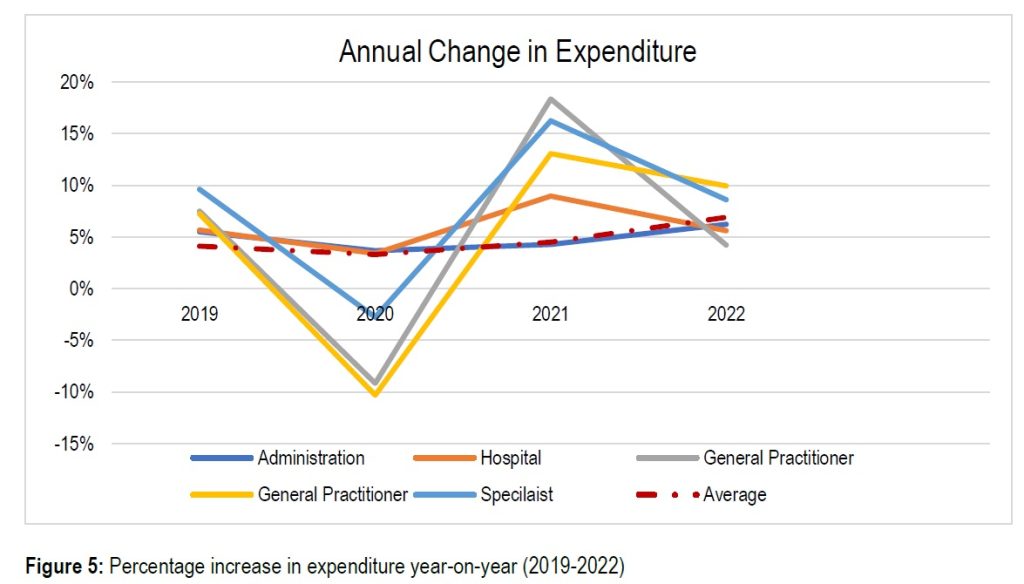

Breaking down the expenditures, McHugh said that medical schemes spent 37% on hospitals and 28% on specialists, while medicine accounted for 16% and GPs a mere 5%. The CMS also noted that hospitals and specialists had seen greater relative increases than other areas. For the essential coverage of hospitals, medicines, GPs, and dentists, that would amount to R363 billion.

Looking ahead with a little maths

One can take simple compound interest to McHugh’s figures, and even applying the CMS’ best-case “reasonable utilisation estimate” of 3.2%, for say 20 years from will mean that costs rise by 87% in today’s rands. That means the NHI’s ‘basic’ coverage would rise to R682 billion and the full coverage amounting to an incredible R2.4 trillion.

But this nothing special to South Africa. The UK’s NHS costs have similarly grown, at 3.6% per annum in real terms. And that growth has to come out of the GDP: from 3.6% of the GDP in 1949-50 to 8.2% in 2022-23, with a surge to 10.5% in the COVID pandemic.

The UK has now put measures in place to constrain cost growth to 1%, but it remains to be seen whether this will be effective without compromising service delivery. How South Africa can even contemplate an NHI where, 20 years from now, private scheme medical costs run to R39 000 per person in the best case scenario.

While McHugh did not mention the recent High Court blow to the NHI Act that found a key part of it unconstitutional, he described the legal challenge process that would see that part sent back to the National Assembly and the president.

McHugh however struck a note of optimism, noting that the public-private partnerships of the COVID pandemic showed a way forward for NHI and universal healthcare in South Africa. The 2024 elections bring the possibility of the same historic benefits for the population as the 1994 ones.