Blows to the Brain: The Hidden Crisis in Rugby and Other Contact Sport

By Kathy Malherbe

A silent but devastating brain disease is casting a shadow over contact and collision sports, particularly rugby. Traumatic Brain injuries (TBIs) as a result of an impact to the head, cause a disruption in the normal function of the brain. Repeated TBIs are linked to an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases like early-onset dementia which has the highest prevalence and is the most concerning. Others include Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, better known as CTE.

How head injuries happen

Dr Hofmeyr Viljoen, radiologist at SCP Radiology, says that there are several types of head injuries common in rugby. ‘The most frequent being TBIs which occur when the impact and sudden movement results in the brain shifting rotationally, sideways or backwards and forwards within the skull. This stretching and elongation causes damage to nerve fibres as well as blood vessels. Surprisingly, a direct blow isn’t always necessary. Rapid acceleration and deceleration, such as during a tackle or fall, can also result in an injury. More severe head injuries may include skull fractures, bruising or bleeding around the brain, all of which require urgent diagnosis and intervention.’

Riaan van Tonder, a sports physician with a special interest in sports-related concussion and radiology registrar at Stellenbosch University, explains that concussions and, even more so, repetitive sub-concussive impacts, result in a cascade of changes at a cellular level, gradually damaging the nervous system.

Although rugby is notorious for heavy tackles and collisions, it took a lawsuit to prompt more widespread awareness. A class-action suit filed in the High Court in London, by former union and league players, accused World Rugby of failing to implement adequate rules to assess, diagnose and manage concussions. Steve Thompson’s, the legendary English hookers, early onset dementia has been one of the sports’ biggest talking points. He was diagnosed in 2020 with this neurodegenerative disease, purportedly as a result of repeated trauma to the brain. The claimants argue that the governing bodies were negligent and that their neurological problems stem from years of unmanaged head injuries. The outcome of this case to be heard in 2025, could significantly reshape the legal and medical responsibilities of sports organisations globally.

What is Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

CTE is a progressive neurodegenerative condition strongly linked to repeated head impacts. It has been implicated in memory loss, mood disturbances, psychosis and, in many cases, premature death. It can only be diagnosed after death at autopsy, where researchers examine brain tissue for abnormal protein deposits and signs of widespread degeneration. Despite this limitation, mounting evidence is forcing sports organisations, including rugby authorities, to confront uncomfortable truths about how repeated head trauma can alter lives permanently.

Uncovering the extent of the problem

In 2023, the Boston University CTE Centre released updated autopsy findings from its brain bank. Of 376 former NFL player’s brains studied post-mortem, 345 had been diagnosed with CTE, a staggering 91.7%. While brain banks are inherently subject to selection bias, the results remain alarming. For comparison, a 2018 study of 164 randomly selected brains revealed just one case of CTE.

This brain disease isn’t new. Its earliest descriptions date back to Dr Harrison Martland in 1928, who studied post-mortem findings in boxers and coined the term ‘punch drunk’ to describe their confusion, tremors and cognitive decline. What was once confined to boxing is now known to affect athletes in rugby, football, ice hockey and even military personnel exposed to repeated blast injuries.

Radiology’s role in determining head injuries

Although Computed Tomography (CT) scans are not designed to specifically diagnose concussions, they are crucial to imaging patients with severe concussion or atypical symptoms. ‘CT scans rapidly detect serious issues like fractures, brain swelling and bleeding, providing crucial information for urgent treatment decisions,’ explains Dr Viljoen.

‘Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is used particularly when concussion symptoms persist or worsen. It excels in identifying subtle injuries, such as microbleeds and brain swelling that may have been missed by CT scans,’ he says.

‘CTE is challenging because currently, it can only be definitively diagnosed after death,’ he explains. ‘However, ongoing research aims to develop methods to detect CTE in living patients, potentially using advanced imaging techniques like Positron Emission Tomography (PET).’ Most research is focused on advancing non-invasive methods to see what is happening inside the brain of a living person and to track it over time.

Advanced imaging methods

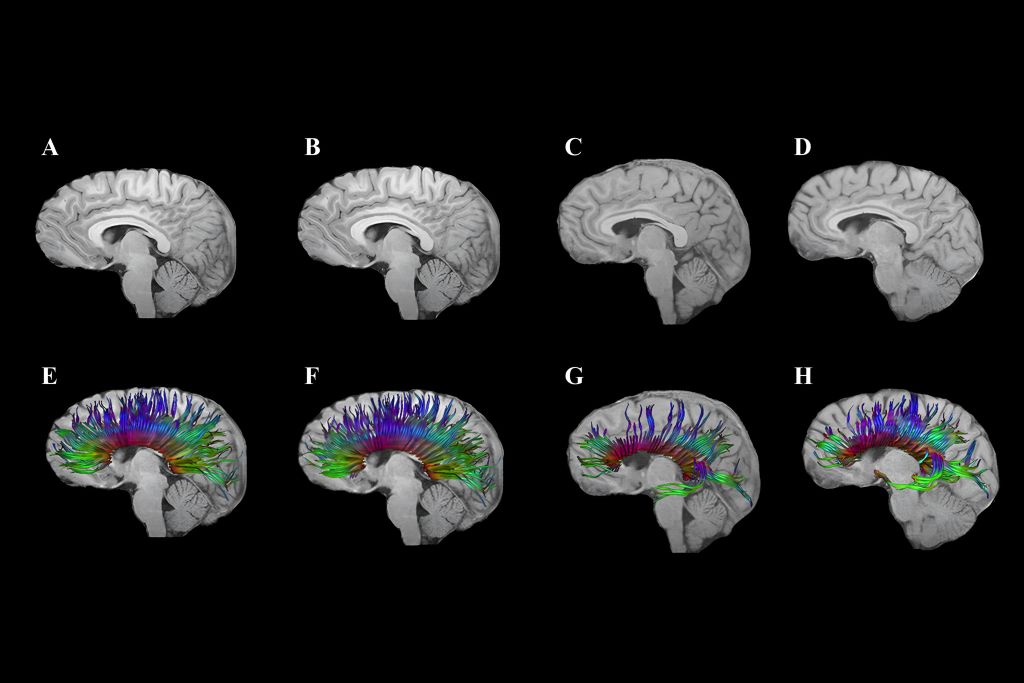

Emerging imaging techniques, such as Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), show promise for better understanding and management of head injuries, especially the subtle effects of concussions. ‘DTI helps identify damage to the brain’s white matter, potentially guiding return-to-play decisions and treatment strategies,’ notes Dr Viljoen.

The biomechanics of brain trauma

Former NFL player and biomechanical engineer, David Camarillo, explains in a TED talk that helmets, although effective at preventing skull fractures, do little to stop biomechanical forces from affecting the brain inside the skull.

Camarillo highlights that concussions and the stretching of nerve fibres are more likely to affect the middle of the brain, the corpus callosum, the thick band that facilitates communication between the left and right brain hemispheres. ’It’s not just bruising,’ he says, ‘we’re talking about dying brain tissue.’

Smart mouthguard technology in rugby

‘Presently,’ says Van Tonder, ‘smart mouthguards are mandatory at elite level. These custom-fitted mouthguards contain accelerometers and gyroscopes that detect straight and rotational forces on the head. Data is transmitted live to medical teams at a rate of 1 000 samples per second.

‘If a threshold is exceeded, an alert is triggered, prompting an immediate Head Injury Assessment (HIA1). Crucially, the system can identify dangerous impacts, even when no symptoms or video evidence is apparent. This is an essential shift in concussion management,’ says van Tonder. ‘It allows proactive assessments rather than waiting for visible signs.’ World Rugby has committed €2 million to assist teams in adopting this technology and integrating it into HIA1.

Brain Health Service

The really good news is that in March this year, World Rugby and SA Rugby launched a new Brain Health Service to support former elite South African players. It’s the first of its kind in the world and South Africa is the fourth nation to establish this system that supports players to understand how they can optimise management of their long-term brain health. It includes an awareness and education component, an online questionnaire and tele-health delivered cognitive assessment with a trained brain health practitioner. This service assesses players for any brain health warning signs, provides a baseline result, advice on managing risk factors and signposts anyone in need of specialist care.

Super Rugby and smart mouthguards

Super Rugby has revised its smart mouthguard policy, no longer requiring players to leave the field immediately for a HIA when an alert is triggered. The change follows criticism from players and coaches, including Crusaders captain Scott Barrett, who argued the rule could unfairly affect match outcomes. Players must still wear the devices but on-field doctors will assess them first; full HIAs will be conducted at half-time or full-time, if necessary. Further trials are planned to improve the system before reinstating immediate alerts.

Where to from here?

Researchers continue to explore ways to reduce brain movement inside the skull during collisions. One innovative idea includes an airbag neck collar for cyclists, which inflates around the head upon impact. It’s closer to the goal of reducing the brain’s movement – and therefore the risk of concussion. However, regulatory hesitation remains a barrier, with no formal cycling helmet approval process currently in place.

The evidence linking repetitive head impacts to long-term brain degeneration is too compelling to ignore. Rugby, like other contact sports, must continue evolving its protocols, technology and player education to protect athletes at all levels … starting at schools.

While innovations such as smart mouthguards mark significant progress, much remains to be done: From regulatory reform to changing the sporting culture that once downplayed the severity of concussion. Van Tonder notes, ‘We’re behind, but it’s not too late to catch up.’

In rugby, the HIA protocol now consists of three stages:

HIA1: Immediate, sideline assessment during the match.

HIA2: Same-day evaluation within three hours post-match.

HIA3: A more detailed follow-up, typically done 36-48 hours later.