Can Exercise Help Reduce Survival Disparities in Colon Cancer Survivors?

Study indicates that higher levels of physical activity may lessen and even eliminate survival disparities.

Physical activity may help colon cancer survivors achieve long-term survival rates similar to those of people in the general population, according to a recent study published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

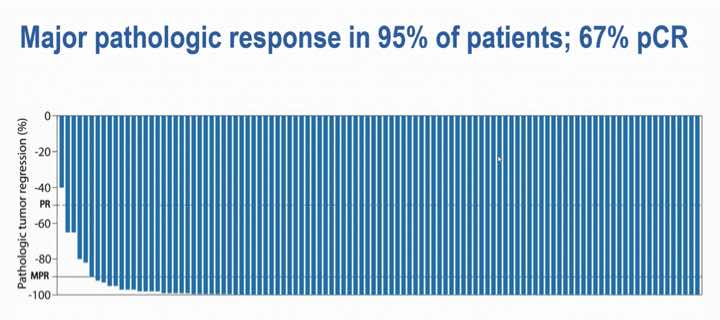

Individuals with colon cancer face higher rates of premature mortality than people in the general population with matched characteristics such as age and sex. To assess whether exercise might reduce this disparity, investigators analysed data from two posttreatment trials in patients with stage 3 colon cancer, with a total of 2875 patients who self-reported physical activity after cancer surgery and chemotherapy. The researchers also examined data on a matched general population from the National Center for Health Statistics. For all participants, physical activity was based on metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per week. (Health guidelines recommend 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, translating to approximately 8 MET-hours/week.)

In the analysis of data from the first trial (called CALGB 89803), for patients who were alive at three years after cancer treatment, those with <3.0 MET-hours/week had subsequent 3-year overall survival rates that were 17.1% lower than the matched general population, but those with ≥18.0 MET-hours/week had only 3.5% lower subsequent 3-year overall survival rates than the matched general population. In the second trial (CALGB 80702), among patients who were alive at three years, those with <3.0 and ≥18.0 MET-hours/week had subsequent 3-year overall survival rates that were 10.8% and 4.4% lower than the matched general population, respectively.

In pooled analyses of the two trials, among the 1908 patients who were alive and did not have cancer recurrence by year three, those with <3.0 and ≥18.0 MET-hours/week had subsequent 3-year overall survival rates that were 3.1% lower and 2.9% higher than the matched general population, respectively. Therefore, cancer survivors who were tumour-free by year three and regularly exercised achieved even better subsequent survival rates than those seen in the matched general population.

“This new information can help patients with colon cancer understand how factors that they can control—their physical activity levels—can have a meaningful impact on their long-term prognosis,” said lead author Justin C. Brown, PhD, of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. “Also, medical and public health personnel and policymakers are always seeking new ways to communicate the benefits of a healthy lifestyle. Quantifying how physical activity may enable a patient with colon cancer to have a survival experience that approximates their friends and family without cancer could be a simple but powerful piece of information that can be leveraged to help everyone understand the health benefits of physical activity.”

Source: Wiley