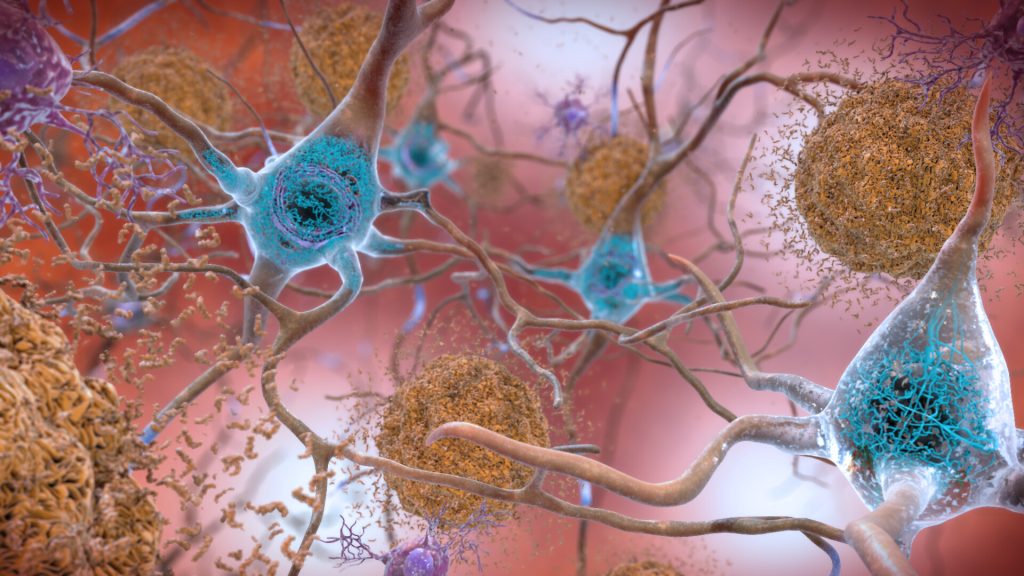

Poor Sleep Quality in Midlife Linked to Cognitive Problems Later on

People who have more disrupted sleep in their 30s and 40s may be more likely to have memory and thinking problems a decade later, according to new research published in Neurology. The study does not however prove that sleep quality causes cognitive decline, it only shows an association.

“Given that signs of Alzheimer’s disease start to accumulate in the brain several decades before symptoms begin, understanding the connection between sleep and cognition earlier in life is critical for understanding the role of sleep problems as a risk factor for the disease,” said study author Yue Leng, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

“Our findings indicate that the quality rather than the quantity of sleep matters most for cognitive health in middle age.”

The study involved 526 people, average age of 40, who were followed for 11 years. Researchers looked at participants’ sleep duration and quality, and had them perform cognitive tests.

Participants wore a wrist activity monitor for three consecutive days on two occasions approximately one year apart to calculate their averages. Participants slept for an average of six hours.

Participants also reported bedtimes and wake times in a sleep diary and completed a sleep quality survey with scores ranging from zero to 21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. A total of 239 people, or 46%, reported poor sleep with a score greater than five. Participants also completed a series of memory and thinking tests.

Researchers also looked at sleep fragmentation, which measures repetitive short interruptions of sleep. They looked at both the percentage of time spent moving and the percentage of time spent not moving for one minute or less during sleep. Added together, participants had an average sleep fragmentation of 19%.

Researchers then divided participants into three groups based on their sleep fragmentation score. Of the 175 people with the most disrupted sleep, 44 had poor cognitive performance 10 years later, compared to 10 of the 176 people with the least disrupted sleep.

After adjusting for age, gender, race, and education, people who had the most disrupted sleep had more than twice the odds of having poor cognitive performance when compared to those with the least disrupted sleep.

There was no difference in cognitive performance at midlife for those in the middle group compared to the group with the least disrupted sleep.

“More research is needed to assess the link between sleep disturbances and cognition at different stages of life and to identify if critical life periods exist when sleep is more strongly associated with cognition,” Leng said.

“Future studies could open up new opportunities for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease later in life.”

The amount of time people slept and their own reports of the quality of their sleep were not associated with cognition in middle age.

Source: American Academy of Neurology