Oxidative Stress Contributes to Multi-drug Resistance in Chemotherapy

Researchers have found that oxidative stress plays a role the inevitable occurrence of multi-drug resistance during tumour therapy, which they report in the Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology.

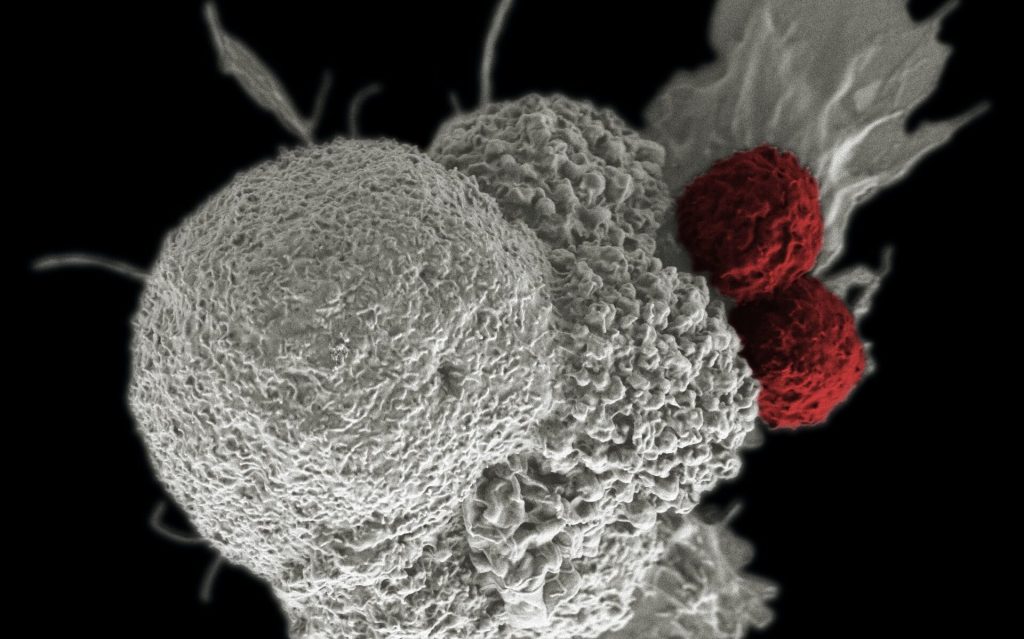

While chemotherapy is a mainstay of cancer treatment, it is often hindered by the development of drug resistance, eventually evolving into multidrug-resistance which renders most drugs ineffective.

Multidrug resistance is responsible for over 90% of deaths in cancer patients receiving traditional chemotherapeutics or novel targeted drugs. Its mechanisms include elevated metabolism of xenobiotics, enhanced efflux of drugs, growth factors, increased DNA repair capacity, and genetic factors (gene mutations, amplifications, and epigenetic alterations).

The most well-known mechanism is the induction of Adenosinetriphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporters by chemotherapeutic drugs. These transporters are highly expressed in cancer cells and pumped out chemotherapeutics to make the treatment ineffective.

Earlier research had shown that non-substrate nanoparticles could induce multidrug resistance by inducing oxidative damage, suggesting that multidrug resistance could be induced by oxidative damage as well as the substrate.

To confirm the this, Yin Jian and his team investigated the interaction of three chemical agents (ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, and doxorubicin) with ABC transporters using a lung cancer cell line (A549) as a model.

Among the three chemicals, doxorubicin is the substrate of ABC transporter and chemotherapeutic drugs, while ethanol and hydrogen peroxide are small-molecule compounds, which have no relationship with the function of ABC transporter.

“When the three substances enter the cells, they can cause significant oxidative stress inside cells,” said Yin.

The elevated oxidative stress induced the expression of transporters, and the elevated transporters reduce intracellular oxidative stress by effluxing oxidized glutathione. In this process, pregnane X receptor played an important regulatory role.

Their results suggested that non-substrate chemicals could also induce ABC transporter expressions similar to chemotherapeutic agents after inducing oxidative damage. This phenomenon could be regarded as a non-specific feedback of tumor cells/ABC transporters to external stimuli.

The conclusions validated the relationship between multidrug resistance mechanisms and oxidative stress. This would help to design advanced strategies on how to enhance this mechanism to more effectively combat ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance.

“Considering that peroxidative damage is the main source of the toxicity of current environmental pollutants, long-term exposure to environmental pollutants could not only induce direct toxicity, but also further threaten human health by inducing multi-drug resistance,” said Yin Huancai, another researcher from the team.

Source: China Academy of Sciences