Scientists Upend the Current Understanding of How PARP Inhibitors Kill Cancer

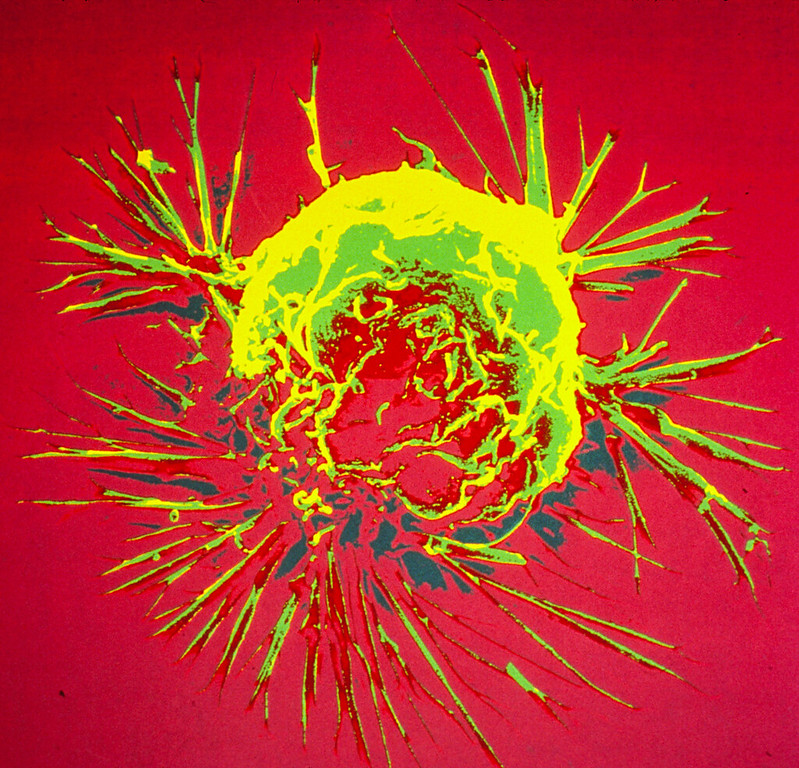

Research by UMass Chan Medical School scientists poses a new explanation for how PARP inhibitor drugs attack and destroy BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumour cells. Published in Nature Cancer, this study illustrates how a small DNA nick – a break in one strand of the DNA – can expand into a large single-stranded DNA gap, killing BRCA mutant cancer cells, including drug-resistant breast cancer cells. These findings identify a novel vulnerability that may be a potential target for new therapeutics.

Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, tumour suppressor genes that play a crucial role in DNA repair, substantially increase the likelihood of cancer. These cancers are, however, quite sensitive to anticancer drugs such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi). When successful, these cancer treatments cause enough DNA damage to trigger cancer cell death. However, the array of different damages potentially induced by these drugs makes it difficult to pinpoint the exact cause of cell death. Additionally, PARPi resistance does occur, complicating treatment and leading to recurrent cancer.

“The conventional thinking has been that single-stranded DNA breaks from PARPi ultimately generated DNA double-strand breaks, and that was what was killing the BRCA mutant cancer cells,” said Sharon Cantor, PhD, professor of molecular, cell and cancer biology. “Yet, there wasn’t much in the literature that experimentally confirmed this belief. We decided to go back to the beginning and use genome engineering tools to see how these cells dealt with single-strand nicks to their DNA.”

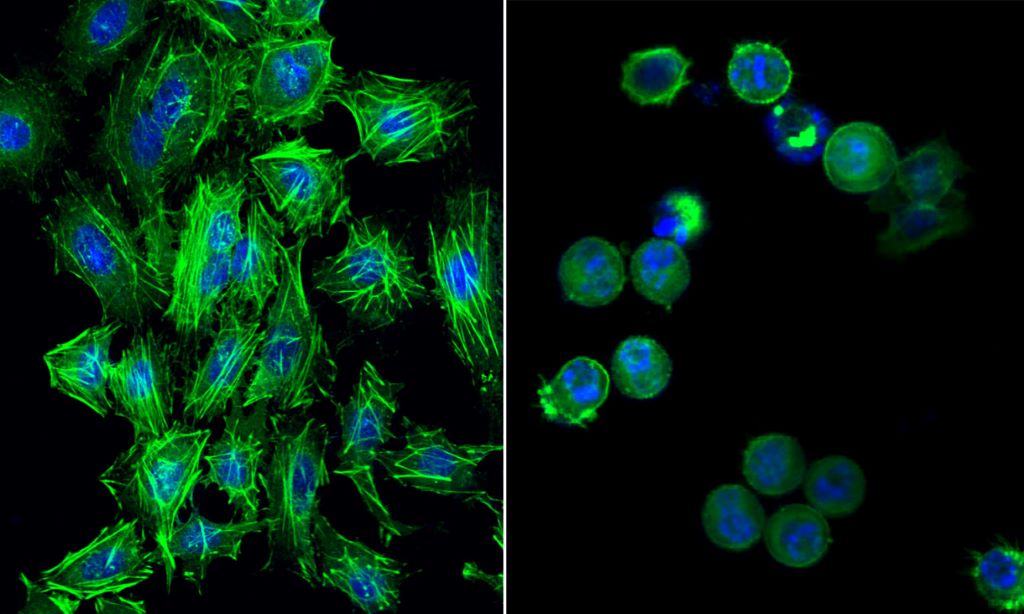

Using CRISPR technology, Cantor and Jenna M. Whalen, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Cantor lab, introduced small, single strand breaks into several breast cancer cell lines, such as those with the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, as well BRCA-proficient cells. They found that cells with BRCA1 or BRCA2 deficiency were uniquely sensitive to nicks. They also found that breast cancer cells that lose components of the complex that protects DNA from unnecessary DNA end cuts become resistant to chemotherapy drugs such as PARP inhibitors. However, restoring double strand DNA repair functions in breast cancer cells did not save the cells from dying, thus demonstrating that these repair functions are not critical for breast cancer cell survival. Instead, the cells become even more sensitive to single strand nicks, which then accumulate and form large gaps.

“Our findings reveal that it is the resection of a nick into a single-stranded DNA gap that drives this cellular lethality,” said Whalen. “This highlights a distinct mechanism of cytotoxicity, where excessive resection, rather than failed DNA repair by homologous recombination, underpins the vulnerability of BRCA-deficient cells to nick-induced damage.”

The findings suggest that PARPi may also work by generating nicks in BRCA1 and BRCA2 cancer cells, exploiting their inability to effectively process these lesions. For cancers that have developed PARPi-resistance, nick-inducing therapies provide a promising mechanism to bypass resistance and selectively target resection-dependent vulnerabilities.

“Importantly, our findings suggest a path forward for treating PARPi-resistant cells that regained homologous recombination repair: to kill these cells, nicks could be induced such as through ionizing radiation,” said Cantor. “By targeting nicks in this way, therapies could effectively exploit the persistent vulnerabilities of these resistant cancer cells.”

Source: UMass Chan Medical School