Stronger Immune Systems in Women Protect against Skin Cancer

Women may have a stronger immune response to a common form of skin cancer than men, according to a preliminary study on mice and human cells.

Men develop more skin squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) than females and their tumours are more aggressive, though it is not clear if this is related to sunlight exposure. Using mouse models to answer the question, they found that male mice developed more aggressive tumours than females, despite receiving identical treatments.

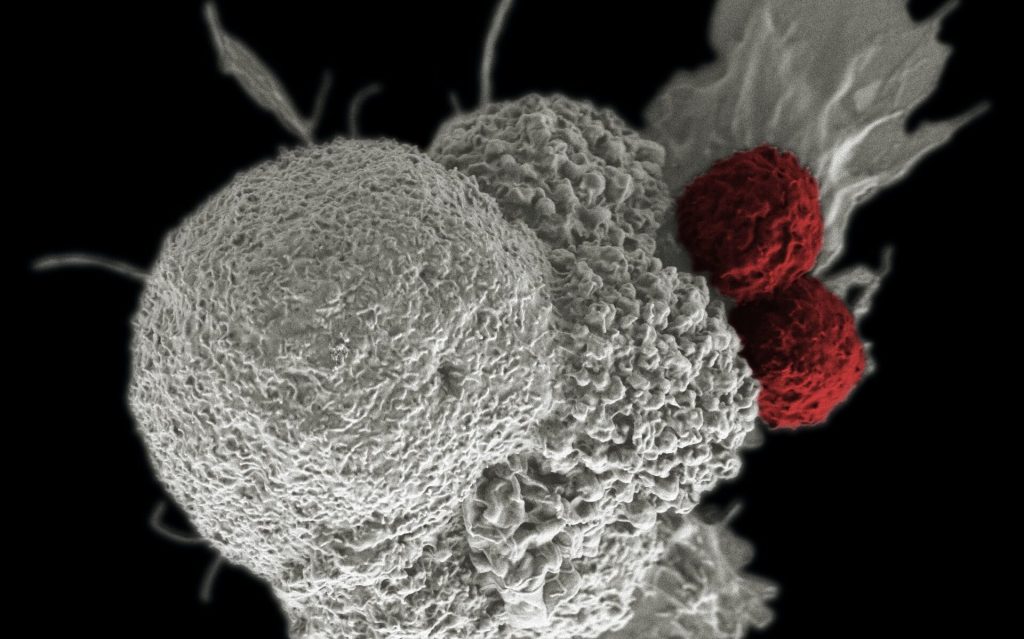

In female mouse skin and tumours, the immune cell infiltration and gene expression related to the anti-cancer immune system were increased, suggesting a protective effect of the immune system.

In keeping with the animal study, 931 patient records collected from four hospitals in Manchester, London and France, the researchers identified that while women commonly have a more mild form of cSCC compared to men, immunocompromised women developed cSCC in a way more similar to men

That suggests the protective effect of their immune system may have been compromised.

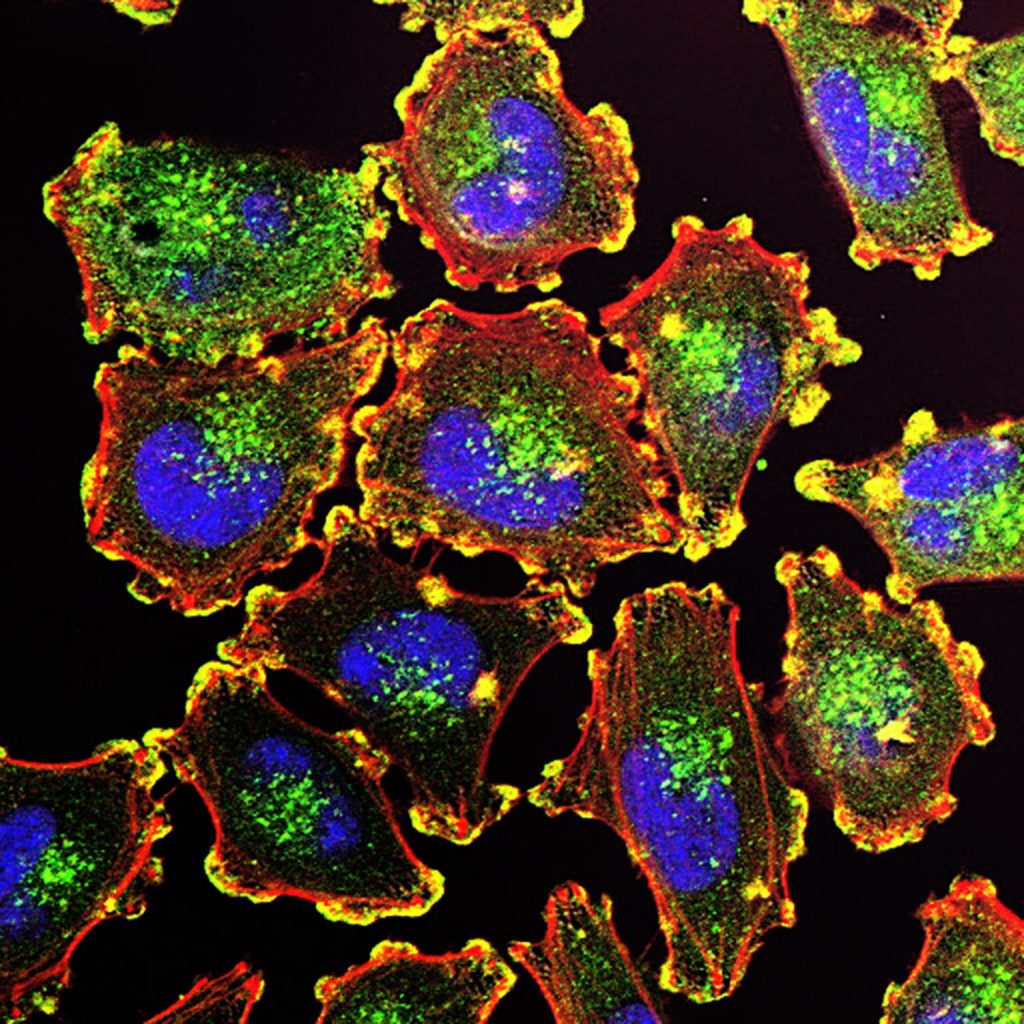

These results were confirmed in a further cohort of sun-damaged skin from the US. In this cohort, human epidermal cells confirmed women’s skin activated immune-cancer fighting pathways and immune cells at sites damaged by sunlight.

The US cohort also that showed CD4 and CD8 T cells, which are important in our immune response to skin cancer, were twice as abundant in women as in men.

The researchers used RNA sequencing to examine differences in male and female immunosuppressed mice and human skin cells.

“It has long been assumed that men are at higher risk of getting non-melanoma skin cancer than women” said Dr Amaya Viros, from The University of Manchester.

“Other life-style and behavioural differences between men, such as the type of work or exposure to the sun are likely to be significant.

“However, we also identify for the first time the possible biological reasons, rooted in the immune system, which explains why men may have more severe disease.

“Although this is early research, we believe the immune response is sex-biased in the most common form of skin cancer, and highlights that female immunity may offer greater protection than male immunity.”

Dr Viros added: “We can’t yet explain why women have a more nuanced immune system than men.

“But perhaps it’s reasonable to speculate that women’s evolutionary ability to carry an unborn child of foreign genetic material may require their immunological system to be very finely tuned and have unique skills.

“Very little is known about how sex differences affect incidence and outcome in infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders and cancer. More work needs to be done. But we feel this study has opened a window into this area, and could one day have important implications on other types of immunologically based diseases.

“And it suggests if doctors are to offer personalised treatment of cancer, then biological sex should be one of the factors they take into account.”

Commenting on the study, Dr Samuel Godfrey, Research Information Manager at Cancer Research UK said: “Research like this chips away at the huge question of why people respond to cancer differently. Knowing more about what drives immune responses to cancer could give rise to new treatment options and show us a different perspective on preventing skin cancer.”

Source: Medical Xpress

Journal information: Timothy Budden et al, Female Immunity Protects from Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Clinical Cancer Research (2021). DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4261